What I learned reporting on N.J.’s Medicaid enrollment woes

I was lucky to receive some wise advice when crafting my proposal for the National Health Journalism Fellowship: “Think of what you’ll have to be covering anyway, then come here and learn how to do it.” I knew we’d have to examine whether all the newcomers to New Jersey’s expanded Medicaid would be able to find care, so that’s what I set out to cover.

Here are a few lessons I learned along the way:

Don’t let your “project hat” give you blinders about the news. We’d already covered Medicaid enrollment delays earlier in the year. As the summer progressed, however, I continued to hear complaints from readers. I belatedly realized what they were telling me was a news story — one that I should switch gears to cover.

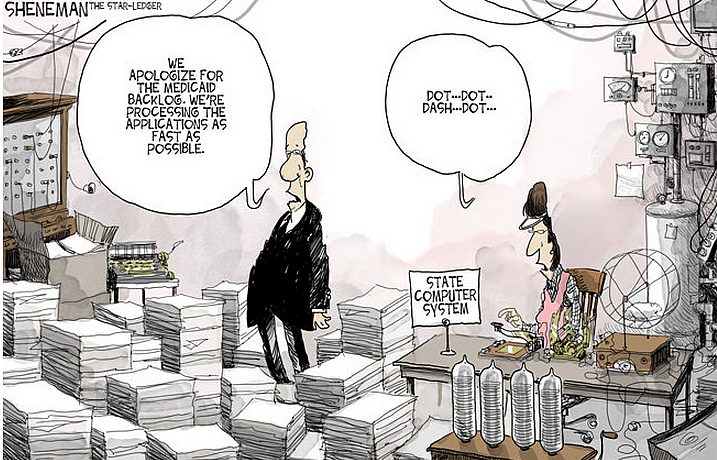

The Annenberg folks graciously agreed to my proposed change in plans. The result was the uncovering of system-wide computer problems that had gone unnoticed because the only people affected were poor.

- As soon as your topic is a mere glimmer in your eye, file those Freedom of Information Act or Open Public Records Act requests.

If you’re lucky, you may get their responses in time to be helpful to your work. I didn’t file mine until I knew exactly what I wanted (silly me!) and I’m still waiting for some responses even though my articles have already been published.

- Our hydra-headed health care system is a sprawling behemoth of interlocking parts with enough acronyms to short out any brain. You need to become familiar enough with it to be able to ask intelligent questions. But at a certain point, you’re going to have to stop preparing and start reporting. Thank goodness for the fellowship publishing deadline; it forced me to plow forward despite feeling vaguely unprepared.

- Want to find out what’s really happening in state government? Look for the union label, as they say. That’s because workers who would normally be afraid to talk to a reporter have some protection if they’re union officials speaking on behalf of their membership.

From those officials I learned key details about the enrollment backlog — stories of stacks of application files blocking hallways, applications stashed under desks, and how the politically connected got their cases handled more quickly. Since photos of the blocked hallways were part of a fire-safety grievance filed by the union, the union rep felt safe sharing them with me. This gave me a visual element the story needed.

Of course, I had to be careful not to get distracted by their workplace issues, which were a separate story. But to the extent our interests dovetailed, these were very productive interviews.

- Listen to your callers — even the rambling ones for whom you can do nothing. Folks call (or email) me hoping I’ll write a story that will magically solve their little chunk of health-insurance hell. Since I can’t allocate my time that way, the temptation is to bail on the call as quickly as possible.

Instead, I listen to them, take notes, and get some contact information. Sometimes I plug their zip codes into HealthCare.gov and tell them where they can find an Obamacare navigator. Then I ask them to keep in touch, and I plop my notes in a folder marked “People.”

When it came time to do my project, I already had real people to interview without having to beat the bushes to find them. They’d already found me — and were grateful for my interest.

- Believe your callers. In the case of my article about the massive delays in Medicaid enrollment, both the state and federal administrations (the first Republican, the second Democratic) insisted there was no problem.

The folks who called me with their Medicaid complaints told a different story, and it turns out they were right. It was “The Emperor’s New Clothes” all over again.

- Trust that if one person is complaining, thousands more are impacted. What struck me about my callers was almost all of them were either temporarily poor (job loss, etc.) or were not poor but calling on behalf of an adult child who was uninsured.

In short, the permanently poor don’t call newspapers to complain about their treatment. They expect to be treated badly by government. I keep a photo taken for my project taped near my desk. It shows a line of people — complete with babies and toddlers — waiting outside on a very cold winter morning for a county welfare office to open. Often when I look at it I think, “If this line were outside the DMV, someone would be fired.”

Images courtesy of Kathleen O'Brien/The Star-Ledger