New California site comparing health care costs and quality still falls short of helping patients

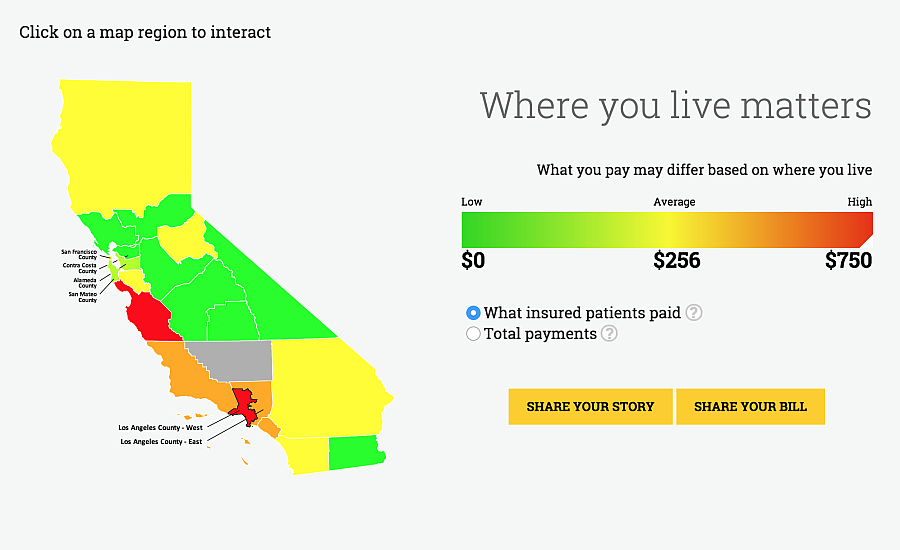

A map from California Healthcare Compare shows variation in costs for total knee replacement.

If you are a health care reporter in California, you should be thrilled at the launch of the new California Healthcare Compare website by the California Department of Insurance and Consumer Reports.

If you are a patient, you may spend several hours on the website and come away feeling more frustrated than informed.

Reporters everywhere highlighted all the cool things you can do with this new tool to see the wide variation in costs by county and in quality by health care entity. USC Annenberg Health Journalism Fellow Rebecca Plevin, for example, described how she and other reporters at KPCC have been trying for the past year to build a database of self-reported price information at Price Check. They have not, however, added to our collective understanding of health care quality. Plevin wrote:

On Monday, California's Department of Insurance unveiled a similar tool, called California Healthcare Compare. It lets consumers look up the costs of more than 100 medical procedures and conditions in their region. It also cracks a nut that #PriceCheck could not: For certain procedures, like childbirth and colon cancer screening, the website also includes quality information about the hospitals and medical groups providing care.

As Plevin and other reporters noted, though, the new website barely scratches the surface of the vast and complex world of health care costs and quality. Here are five great things about the site and five things I hope will be improved over time:

Five pluses

1. The site focuses on what the health insurers actually paid for more than 100 different diagnostic categories. As Chad Terhune at the Los Angeles Times wrote, this is a big advance over much of the cost information floating around out there now.

Publishing the amounts actually paid to hospitals and other providers — rather than just the amount charged — is considered more useful. Insurers often pay just a fraction of billed charges, and a policyholder’s share is derived from the lower, discounted rate.

2. You can make some really interesting comparisons of costs for procedures, including out-of-pocket costs to consumers. This is what Barbara Feder Ostrov did for Kaiser Health News:

Take total knee replacements. In Alameda County, where the surgery’s total average cost for consumers and employers is listed as more than $55,000 – the highest in the state — the site estimates average out-of-pocket costs at only $86. In comparison, the total cost for the same surgery in Santa Clara County is just under $40,000 – but the average out-of-pocket cost is about $300.

3. The site offers some fairly easy to understand maps that show the price information by county. So, for example, you can see quickly that the Inland Empire counties are about average for costs of vaginal births at around $22,000, but that Monterey, Santa Cruz, and San Benito counties are sky high at more than $35,000.

4. The site links directly to the Price Check project, and encourages patients to share their medical bills to help improve price information.

5. The explanations of how the ratings were developed and what is included in the quality measurements are fairly straightforward.

Five minuses

1. The site provides some seemingly detailed information about hospital and physician group quality on a few common medical procedures. But the measurements in many cases are several degrees off the mark from what is necessary to allow consumers to make meaningful decisions. For example, the measurements don’t take into account the patient load of the hospital or physician group. They are rating hospitals that see hundreds of patients a day against hospitals that see relatively few.

2. The measures don’t appear to take into account the mix of patients seen. For example, if a hospital sees more patients through its emergency room than other hospitals – or whether it even has an emergency room. Or whether its patients skew older or tend to have more complicating factors such as obesity or high blood pressure.

3. The measures don’t appear to take into account the severity of the various cases seen. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs uses a basic method for making sure that its measurements incorporate severity. It does this, according to its website, by taking into account “how sick patients are at a single hospital compared to the national population adjusted for the proportion of patients that have surgical or medical problems.”

4. Another way the effort falls short is that Healthcare Compare doesn’t always measure the things that are the true indicators of health care quality, even though the site’s measurements are presented as authoritative. (I will explore this in more detail in my next post.)

5. Perhaps the biggest disappointment is the inability to truly link the cost data to the outcome information. Having cost information at the county level is interesting, for sure, but to be able to pair it directly with the outcome information that is provided at the provider level would be much more powerful. We did it at the Orange County Register more than a decade ago, so I’m certain it would be even easier today, were there the political will.

All of these factors are knowable, by the way — they’re fully logged and stored away in hospital databases and government offices everywhere from DC to Sacramento. And yet, because there are no requirements that much of this data be shared and no significant investment in making the quality and price picture clear, we still have a hodgepodge of efforts, ranging from nonprofits and media groups to local and federal agencies, each providing small slices of quality and price information. If there were more data sharing and a better platform for making it searchable and actionable, an effort like Healthcare Compare would be useful not only to reporters but also to anyone facing an important health care decision.