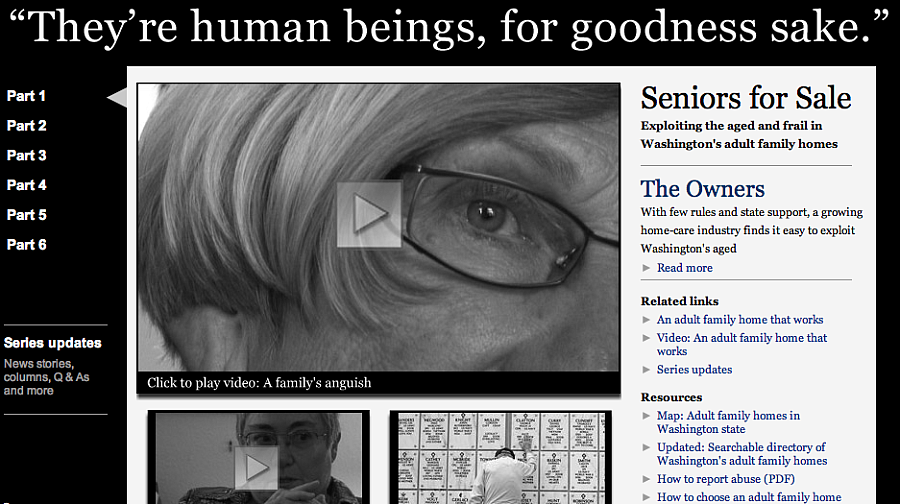

Small Lessons from Michael Berens' Big Investigation of Senior Abuse

Michael J. Berens, investigative reporter at The Seattle Times, spent 20 months working on the Seniors for Sale series.

"I'm a rare breed," Berens said. He's one of a shrinking cadre of newspaper reporters given time to work on large investigative projects. But, he told this year's California Health Journalism Fellows, "I started where you guys are right now. You start small."

In his keynote address that began the Fellows' seminar on Thursday evening, Berens said that is possible to develop tools that can elevate daily stories into something better. Start small and chip away at big stories by writing smaller pieces in a series, he said.

According to the Population Resource Center, by 2030 one in five Americans will be 65 years or older, compared to one in eight today. For Berens, the startling statistics about this country's elderly population is aging raised a big question: "Where are they all going to go?"

When he came across a disciplinary notice for an adult family home, his interest was piqued. "I'd never heard of an adult family home. It was sort of simple curiosity," he said. Berens explained the system in Washington in his first report in the series:

Twenty years ago, the state Department of Social and Health Services began licensing homeowners to provide spare bedrooms and care for the old or frail who might otherwise have to live in nursing homes.

These private residences - called adult family homes - were marketed as opportunities for seniors to live in cozy settings and familiar neighborhoods, close to family and friends, with more freedom and superior care.

The owners were given freedom, as well. To encourage this new industry, the state imposed few regulations - no requirements for a minimum level of employees or even, for many years, liability insurance.

Today, Washington is lauded nationally as a leader in community care options for seniors.

But inside the state's 2,843 adult homes, thousands of vulnerable adults have been exploited by profiteers or harmed by amateur caregivers, an investigation by The Seattle Times has found.

Anyone can investigate these kinds of facilities in their own communities, he said. Reporters can also pursue stories about "rebalancing," federal government program that rewards nursing homes for moving their residents back into the community. He explained it this way in the third part of his series:

In reducing its nursing-home population, [the Department of Social and Health Services] used a system that assigned a dollar value to every nursing-home resident. The agency then evaluated caseworkers by how many Medicaid clients they moved to less-expensive placements and how much money it saved, according to DSHS records obtained by The Times.

Depending on the year, employees were given quotas as high as four residents per month; some caseworkers were told they must achieve their quotas in order to justify their jobs.

The agency refers to this process as "rebalancing."

The program sounds positive in some ways, but Berens wondered, what happens to those people? Do they still receive appropriate care?

Berens is an advocate of something he calls "quantification." "Some people subscribe to the belief that a perfect story is 'he said, she said,'" Berens said. But his perfect story is "he said, she said, now I'm going to tell you which one's lying." He does this by diving into data to prove or disprove sources' claims, in this case about facilities' safety records. He will explain how he used licensing records and death certificates and spreadsheets in his reporting in a session with the fellows on Friday afternoon. State ombudsmens programs are a great resource for journalists who are looking for sources.

"What resonates with our readers is that these are ordinary people," Berens said. An ombudsman can help you find those sources whose stories readers can relate to.

One more of the "big untapped stories," Berens said, is the commission-based home placement industry, which is purports to help families find places where their elderly relatives will be cared for, but often do not check facilities' past violations.

Berens says that it is also powerful to reach out on several platforms. Combine your print reporting with documents, images and video."If you get this choice, one of my hard and fast rules is that I take videos and photographers with me on the first interview," Berens said.

Read prior fellows' projects about the elderly:

Disabled and Elderly Living on the Edge

Sign the Check, Look the Other Way

Cultural tradition traps Chinese elder-abuse victims in U.S.

The Forgotten Wounds: Senior Abuse Needs Urgent Attention

Innovations Bring Depressed Elders Back from "Living Hell"

Is quality of elder care in jeopardy?

Read more about how Berens relates to sources and about reporting on the elderly:

Serious Complications: What Andy Rooney Might Say About His Death

Delivering Together: A Partnership With Ethnic Media on Senior Health Stories

Aging and the 2010 Census: Dig Deep into Diversity

2011 California Health Journalism Fellow Rachel Dovey is investigating what resources exist for a rapidly aging population in the small town of Novato. Over the course of the weekend, the California Health Journalism Fellows will be discussing health access and disparities, health care reform, food deserts, and best practices on the Internet. Get updates about this weekend's fellowships seminar in real time at the Twitter hashtag #chjf and here at Center for Health Journalism Digital.