The Great Potassium Iodide Panic of 2011

The Great Potassium Iodide Panic of 2011 has peaked and begun to ebb. There were no child-flattening stampedes at Wal-Mart. No Jersey Shore-style girl fights in the aisles at Safeway. In fact, you might even be thinking no one got hurt this time around.

But what about next time? Did we learn anything about how our lightning-fast social media rumor mill works? It used to be, in the dinosaur days of news, that if Walter Cronkite didn't mention it, it wasn't relevant. Or, if someone tried to start a panic, all it took was a little reassuring Dan Rather sweater vest action and, poof!, the whole thing winked out faster than a blown cathode TV tube. Nothing left behind but an acrid smell and silence.

But now our media are all-pervasive. Once the potassium iodide panic began amid Japan's earthquake-driven nuclear crisis, most of us were getting messages saying some version of "Don't Panic" on Twitter, on Facebook, and on the Internet every time we tried to check our email. And that was the responsible media thing to do, right?

Here's what may be wrong with that approach, neurologically speaking.

Imagine you're nine years old. You are walking across a darkened, empty gymnasium, with only the red EXIT signs casting a dim glow on the squeaky hardwood floor. Rationally, you know you're fine, but your mouth is dry, and you can feel fear rising like fog. Almost involuntarily, you think the words"don't panic." Don't Panic becomes a chant that beats faster and faster, like your heart. Don't panic. Don'tpanicdon'tpanicdon'tpanic.

How far would you get across that basketball court before you broke into a run?

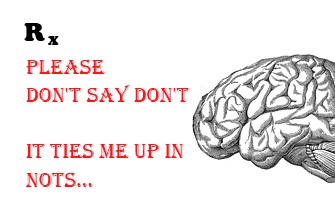

Does saying Don't Panic, over and over, actually induce a panic? There is a body of interesting work in the field of neurolinguistics that tries to sort out how our brains process what's called a negation. The bottom line is that we humans don't do so well with the don'ts.

Did reading that last sentence make your mind stutter? Just for a second? That's called an N400 - a number that represents the amount of time it takes your neurons to regroup. Or maybe the phrase tangled you enough that you experienced an N600. See, without those verbal snarls, when you're reading or hearing a narrative of any kind, your mind is flickering in many areas, neurons firing and spiking.

In fact, when you hear a word that represents a part of your own body, like "arm," especially when the word is used as part of an action, the section of your brain devoted to actually moving your arm lights up. But when negatives, or negations, pop up, our brains tend to glitch for a big fat chunk of a millisecond. However, processing the negation doesn't necessarily stop a later signal. For example, if you were told, Don't move your arm, the part of your brain devoted to arm movement would often still light up. Even when the negation is heard, that signal can still occur, though it may be dampened a bit.

In real world terms, repeating (or reading) the words vaccines don't cause autism over and over may end up leaving behind a feeling more like vaccines [brain glitch] cause autism.

But has this ever been tested? I contacted Dr. Friedemann Pulvermuller, a Cambridge neurolinguistics researcher working for the Medical Research Council of the U.K., to ask, based on his extensive research, if a brain specifically hearing the words don't panic over and over, would hear panic. He pointed out that panic is a behavior, associated with physical action. And words about overt actions stimulate the motor system in the brain almost instantly."You can actually see movement from thought to action." A modulator, such as don't, "may modulate, but won't entirely eliminate the stimulation of the region, so...yes. It could."

But isn't panic an abstract concept for many people? He said his lab looked at whether or not abstract sentences are treated differently, an idea he tested by embedding an action word in an abstract phrase, such as "grasp the concept." The brain response to the word "grasp" stimulates the hand-grasping motor part of the brain, even when the word is used in an abstract way.

But does saying don't do it actually causean irresistible compulsion in another person to do it? The fields of hypnosis and neurolinguistic programming (NLP) both recognize that negative suggestions are often interpreted by our brains as positive.

For example, if you're trying to win a coveted waitressing award, zipping across a crowded restaurant with a tray full of water glasses, and you're chanting to yourself don't drop the tray over and over, your brain instead hears drop the tray and because of your chanting, you (and your customers) are actually more likely to end up drenched.

Children are believed to be more susceptible to this effect. If you tell a toddlerdon't touch that, they are almost compulsively drawn to the idea of touching it. Which makes sense, neurologically: your frontal lobes, which are crucial to performing higher-order impulse control and delayed gratification, only finish developing in your mid-to-late twenties.

So if you're giving instructions or counseling a patient about behaviors or reporting a story, how do you, frame a message, when you know it may be best to avoid the don't word? I found one of the best, succinct answers to this question from a commenter named Seccus on a Neuro Linguistic Programming discussion thread. I've edited it for typos and clarity only:

In cognitive terms, therefore, "not wanting to steal" (so to speak) is not the same as "being honest", and tends to keep the "negative" [steal!] idea at the forefront of the mind. It also subjectively suggests a single dead-end rather than a general direction to go. This is why, whilst a wish to avoid can indeed motivate, and powerfully, it is generally not seen in NLP as being as useful as a positive intention.

In other words, an article headlined Make A Disaster Kit In Three Easy Steps, with a sidebar that mentions that potassium iodide is unnecessary and may even cause harmful side effects[MS1] , may be more effective at slowing a Potassium Iodide Panic than the words, Don't Panic. And then there's The Onion's approach:Nuke Fears Spark Potassium Iodide Poisoning. Humor, while rarely studied in the research world, may be one of our most effective tools. When it comes to slowing a panic, I'd give it at least an N900.

In other words, an article headlined Make A Disaster Kit In Three Easy Steps, with a sidebar that mentions that potassium iodide is unnecessary and may even cause harmful side effects[MS1] , may be more effective at slowing a Potassium Iodide Panic than the words, Don't Panic. And then there's The Onion's approach:Nuke Fears Spark Potassium Iodide Poisoning. Humor, while rarely studied in the research world, may be one of our most effective tools. When it comes to slowing a panic, I'd give it at least an N900.

Got any personal experiences you'd be willing to share about moments when thinking Don't Do It seemed to become a command (if not a compulsion) to Do It? Does your personal experience make you feel like the more you try to tell yourself (or your patients!) to NOT do an unhealthy behavior, the worse the craving to indulge becomes? Or have you got any tips to share on how best to stop a panic once it has begun - given today's immersive media experience, since ignoring it to death just doesn't seem to be an option? Express yourself in the comments section.

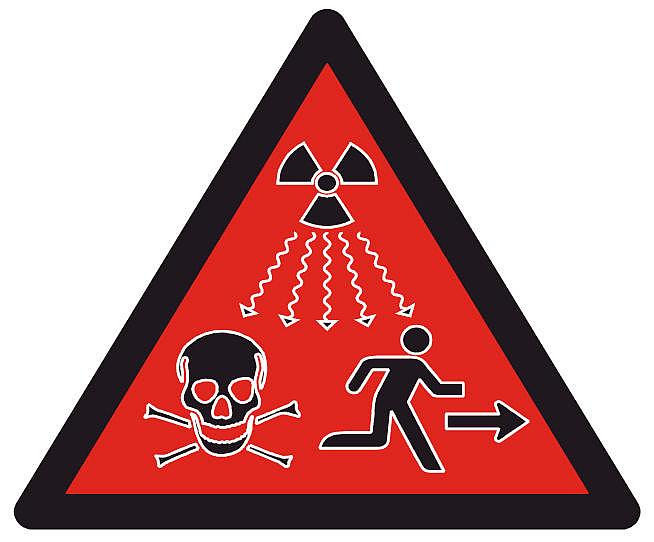

Photo credit: International Atomic Energy Agency via Wikimedia Commons

Graphic: R. Jan Gurley