Dreamer stress in the age of Donald Trump

This article was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's National Fellowship.

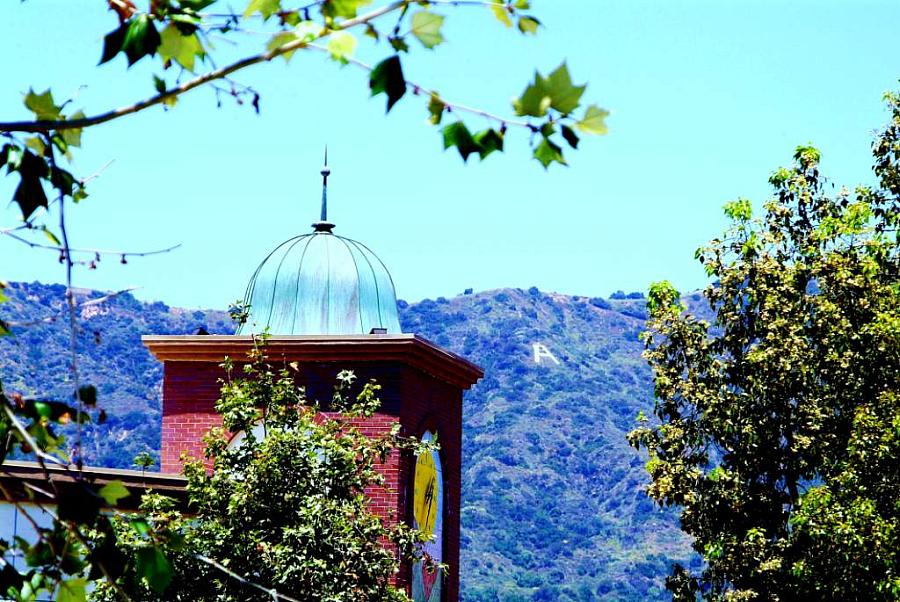

Laura Isais and Oscar Alvarez share their experiences of being undocumented during the election campaign. Jenny Manrique / Univision

Click HERE for SPANISH version.

BERKELEY, California – On a recent Wednesday night, an unusual meeting is taking place.

Inside a house, 10 students gather in a circle, sitting on the floor or on beds, to share their most intimate feelings. Home to only undocumented students, the house has been dubbed the "House without Borders." Mexican flags hang from almost every corner, and the spoken language is Spanglish.

And one by one, they share about the emotional toll of being undocumented.

When the roommates first began meeting three years ago, they discussed homework and basic rules for living together. But things started to change in the middle of 2015, when one of them, Oscar Alvarez, first saw a psychologist for depression. He realized the long silences among his roommates spoke volumes.

“We can talk about this,” he told them.

I first interviewed Alvarez, now 21, a year ago, when he told me about the then-unnamed house. Through him, I met his roommates and a dozen University of California at Berkeley students who also opened up to tell me their stories about the challenges of being undocumented.

Some 400 of Berkeley’s 36,000 students are part of an Undocumented Students Program (USP), which offers undocumented undergraduates on campus academic counseling, legal support and financial aid. They can access education as part of the government’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, a benefit that protects from deportation about 1.2 million young undocumented immigrants who entered the United States as children.

Many of the students I interviewed reported that the last few months have been exceptionally “toxic” on campus. A number of students explicitly asked not to be included in this article, citing a “xenophobic” and “negative atmosphere” due to the presidential election.

“The beginning of the semester was particularly draining,” Alvarez says. He sits on his bed in one of the old, wooden house’s three rooms.

Oscar was born in Puebla, Mexico, but came to the United States when he was two, along with his mother, younger brother and older sister. Today, he has no memories of his homeland. His identity as an undocumented immigrant never affected him until he was applying for college. “They told me: you don’t have social security? Then you can’t apply for any loans or scholarships. That’s when it began to hit me – hard.”

Now he is in his fourth year studying Educational Policy at Berkeley. His emotional rollercoaster has intensified because of Trump’s immigration proposals. Yes, “the crazy wall idea” worries him, he says. But his biggest fear is Trump’s threat to deport 11 million undocumented immigrants – like him.

“There is a lot of bullying on campus because of political tensions,” he says. “This makes a lot of kids tired, mentally and emotionally.”

A Cardboard Wall

Juan Prieto, a Berkeley student and USP’s social media coordinator, remembers the days following a cruel experiment by conservative activist James O’Keefe in early September. On campus, O’Keefe built a cardboard brick wall next to a paper cutout of Donald Trump, as part of his Veritas Action Fund project, in which he films undercover videos to spread radical ideas or to expose “the lies” of the Democratic Party.

The experiment sparked its own protest as dozens of students linked arms and chanted “undocumented and unafraid!”

Prieto, who is an activist for immigration rights, was there.

“For the first time, I was scared of saying I was undocumented,” Prieto says during an interview at Milano Cafe, a common hang-out for students. “After that, for three days, I didn’t leave my room.”

“They shouted all sorts of insults at us: illegals, thieves, that we didn’t belong here.”

He began to miss essay deadlines and took to frequently calling his parents, who live in El Centro, California, near the border. He told them about his fears.

The bullying happened online, too, where more vocal students received threats and vulgar messages. Thanks for telling me you’re illegal. I’m going to find you, one read.

The USP received threatening messages, including one that demanded a list of names of all the undocumented students at Berkeley so that they could be reported to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“It’s still difficult for me to go to class. Everything seems irrelevant because there are bigger things happening [with the election],” Prieto says. “It is a burden that whoever wins, we still don’t have any guarantees. Obama made many promises, too, but he deported three million people.”

Healing Circles

Today, these memories resurface in “Healing Circles.” Diana Peña, the USP’s psychologist here, began to facilitate the sessions in response to aggressions on campus. Some 20 students meet to discuss discrimination and how to confront it.

“The cost of combatting racism, discrimination and xenophobia, even in a community as diverse as Berkeley, is very high,” Peña says in an interview. She is the only psychologist affiliated with USP, a center that is privately-funded, independent from the university.

Last year, the University of California system approved a budget increase from $40 million to $58 million for the 2018-2019 school year. The system also decided to hire 85 new mental health professionals for all California universities, although it is not clear how many will work directly with the undocumented population.

“We cannot deny the impact that the national political discourse has on different immigrant communities. It’s clear that part of the anxiety they live with is caused by who the next president could be,” Peña says.

In her consultation office, Peña has seen first-hand so much of what she learned in theory from the literature on immigration and trauma. “I have patients afflicted with PTSD because of the experience of migrating, the exile itself, or the trauma of the socioeconomic conditions they grew up in. And, on top of all this, there is the stress over legal issues and language barriers.”

Peña is bilingual. In many of her sessions, Spanglish is the norm. She says that half of her student-patients switch back and forth between English and their native language, which allows them to more easily access their brain’s centers of emotions. “People feel more comfortable expressing their emotions in their own language.”

“You don’t need a doctor. Just pray.”

Self-compassion is a word Laura Isais, 23, learned in therapy. “There’s a ton of baggage you bring from Mexico,” she says. Laura, who has dark, expressive eyes and is finishing her Bachelor’s in English so that she can apply to law school, was born in Morelia, Michoacan, but left when she was eight. Her family owned a grocery store there until financial problems forced them to cross the border.

“Since I was a little girl I felt inferior for not being born here, and for not knowing the language. All of this creates a lot of sadness and stress,” she says.

A few months ago, Laura told me how she still suffered panic attacks stemming from the bad news she received in 2014. Her father was diagnosed with a heart condition and could not get a transplant in California. He returned to Mexico. In the transition, he divorced his wife. Laura’s mother now lives in Fontana, in the county of San Bernardino, CA, taking care of foster children.

Isais had to work several shifts to help her family. She has slowly found a balance. Not only has her self-esteem improved, but she found an internship at a law firm for immigration.

“My parents only hoped for me to get into a technical college. Now, no one is going to stop can me getting my Ph.D.,” she says. This optimism follows months of therapy lifting her out of severe depression. Her friends said she didn’t need to go to therapy because she was not “crazy.”

And now, she is trying to stay healthy in the face of the election cycle.

“Almost all of us can remember people telling us to ‘go back to Mexico’ during a discussion about Chicano culture or immigration policy,” Laura says. “People have become more racist during this campaign. I’m scared to think that someone could hate me so much for not having papers.”

Isais used to live in the House without Borders, where she met Alvarez. She shared in the process of creating the first healing circles. She remembers how difficult it was to confront “the taboo about mental health in the Latino community.”

“I have many friends whose parents tell them: just pray, pray, do exercise, distract yourself. You don’t need a doctor,” she says.

When Alvarez and Isais recognized that they needed therapy, they opened the door to other students. Some students dared to sit in Peña’s office. Others kept their feelings to the confines of the house’s couch, where racism was the number one topic.

Isais admits that she still has problems identifying herself as a Latina in Berkeley.

“Sometimes I lack the confidence to say the truth that I am undocumented. The problem isn’t if they ask you if you’re documented or not, it’s how to navigate a system that wasn’t made for you.”

Faith in Humanity

Kimberly, 19, recently took Laura’s place in the house. Like Prieto, she is from Mexicali. She is also member of RISE (Rising Immigrant Scholars through Education) that looks to empower the undocumented community.

She quickly bonded with her roommates during the protests against O’Keefe’s symbolic Trump wall. “I get really mad at discrimination, and in the house we talk a lot about it, but we don’t want anyone to see us as weak,” she says.

She’s looking ahead, anxiously, to Tuesday’s election. “What scares me isn’t that man aiming to be president. It’s the number people that follow him,” she says.

[This story was originally published by Univision News.]

[Photos by Jenny Manrique/Univision News.]