In pockets of Nashville, diabetes runs rampant

First Day Main Bar: While a citywide effort promotes healthier eating and more physical activity, there is no comprehensive, coordinated campaign to target diabetes where it is most prevalent.

Tom Wilemon wrote the series, Diabetes Hot Zone, for The Tennesean with support from the 2012 National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC’s Annenberg School of Journalism. Other stories in the series include:

With dramatic weight loss, Nashville diabetes counselor sets example

Deonta Ridley is trying to get out of a disease hot zone.

He lives at Riverchase Apartments, a place where the four ZIP codes in Nashville hardest hit by diabetes converge. On a recent Saturday night, he came out of his room to find his diabetic grandmother lying on the couch with the television running. As he knelt down to make sure Nellie Diaz was breathing, he heard gunfire.

“Somebody got killed and she slept right through it,” he said.

An 18-year-old high school senior, Deonta is weighed down by his environment and the pounds on his body.

Walls of speeding vehicles along busy thoroughfares cut off his apartment complex from Nashville’s thriving downtown and the city’s gentrifying east side. Without a car in the household, the closest grocery is a Piggly Wiggly a mile’s walk up Dickerson Road past a liquor store, a candy store and competing convenience stores selling fast-food pizza. Violent crime around the complex — three shootings in the past six months, including one that injured a police officer — make people afraid to get out and exercise. Years of consuming fattening foods provided by family members with bad eating habits have added to Deonta’s girth.

By his junior year, he weighed nearly 400 pounds and was on his way toward continuing a family cycle of obesity-related diseases. His uncle died of complications from kidney failure. His mother had a stroke.

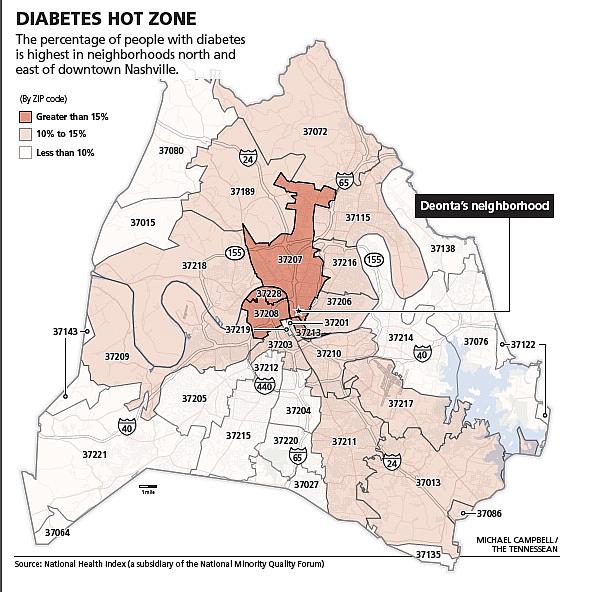

Deonta lives in the diabetes hot zone — a cluster of predominantly African-American, inner-city neighborhoods where diabetes rates soar to more than double the Davidson County average. While Nashville has launched a citywide effort to promote healthier eating and more physical activity, there is no comprehensive, coordinated campaign to target diabetes where it is most prevalent.

The non-communicable disease of diabetes might as well be catching in these neighborhoods. More than 18 percent of the people who live in the 37208 and 37218 ZIP codes have diabetes, according to data from the National Health Index. Five other ZIP codes have rates of 15 percent or higher.

The national average is 8.3 percent.

“We need to have community-based programs to help people with diabetes manage their disease,” said Gary A. Puckrein, president of the National Minority Quality Forum. “It’s got to be in the community.”

The programs that target these Nashville neighborhoods are understaffed, sporadic or nonexistent. But a few pilot projects show that they can make a difference.

Diabetes defined

Nationwide, if current trends continue, one in three Americans will be diabetic by 2050 — and people of color are most at risk. Blacks are 77 percent more likely than whites to be diagnosed with the disease, and the odds for Hispanics are 66 percent greater than for whites, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Diabetes, a disease that stops people from processing blood sugar normally, can have deadly consequences. It leads to heart disease, hypertension, blindness, kidney failure and amputations.

“This should be a shouting match from the rooftops,” said Ann Albright, who heads diabetes prevention for the CDC.

“This is not yelling fire in a crowded theater. This is where we’re headed if we don’t change the course we’re on.”

The problem is simply too big for just physicians to address, said Dr. John E. Anderson of The Frist Clinic, who serves as president of medicine and science for the American Diabetes Association.

“We need everybody with all hands on deck,” Anderson said.

Alice Randall, a Nashville novelist whose latest book, “Ada’s Rules,” examines weight issues in the African-American community, says history and fate will be determined by what people do.

“Health disparity has become, I think, the dominant civil rights issue of the 21st century in America,” Randall said.

Deonta's story

Deonta is trying to change and has lost about 80 pounds. In November, he was among 5,000 Nashvillians who participated in the Mayor’s Challenge 5K.

A toothache put him on that path. He went to a school clinic operated by United Neighborhood Health Services last year with a painful molar. A nurse there insisted he get a physical and signed him up for Teen Choice, a state-funded program aimed at helping minority youth lose weight.

If that toothache had occurred this year, he would have missed that opportunity. The program was funded for only a year.

He learned he had elevated cholesterol and was at risk for developing diabetes and high blood pressure. But dropping the pounds has been a slow process.

“It gave me a huge wake-up call,” Deonta said. “I know that I may not lose all the weight that I want to, but it doesn’t mean I have to stop trying. I just go one day at a time.”

Deonta likes to eat. His grandmother craves sweet things, and he also has a fondness for sugar. He drinks the real thing instead of diet Coca-Cola, can’t resist buying homemade candy at the Nashville Farmers’ Market and will split a package of Little Debbie cupcakes with his grandmother.

He doesn’t go to the Margaret Maddox YMCA in East Nashville to exercise as often as he used to because his uncle, James “Punkin” Ridley, isn’t around to drop him off any more. The uncle, who had been on dialysis for 10 years, died in June of a heart attack.

Deonta and his younger brother went to live with him and their grandmother as elementary school students after their mother, Bernell Ridley, suffered a stroke at age 33. Disabled with stroke-related Alzheimer’s, she lives in a nursing home and is in a wheelchair.

“I never really knew my dad,” he said. “My mom, she remembers me and my family but sometimes has some memory loss.”

More deadly than guns

Deonta grew up being cared for

Deonta burned off those calories in his early years, running around in his neighborhood. But he became a homebody at age 14 when another teenager was shot and killed near his home. He was on his way back from the McFerrin Park Community Center with his little brother when he saw a television van broadcasting live from his apartment gate about the teen homicide.

“I think to myself, ‘Is this the end? Is this end of me?’ ” he said. “ ‘Will I finally realize how it feels to have a bullet, to get shot with a bullet?’ It kind of drove me to where I was having nightmares of getting shot. It just really shook me up.”

His grandmother told him, “It wasn’t y’all’s time. God wasn’t ready for y’all. Don’t be afraid.”

In her family, weight-related illnesses have been more dangerous than guns. Hypertension caused her son’s kidneys to fail and put her daughter in a nursing home. It’s often a sister disease to diabetes.

Diabetes eased into her life as gently as yeast rising in bread, but it announced itself like a bolt of lighting. A bright light flashed across her eyes on a warm summer day two years ago, then transformed into a yellow chick with a black beak.

Her glucose level was so high she was hallucinating, high enough for her to be in a coma, her doctor told her.

“I didn’t even know I had sugar,” said Diaz, who is 71. “I had been walking around all this time and didn’t even know I had sugar.”

Diaz began taking insulin injections three times a day. Since the diagnosis, she has been hospitalized four times.

Targeting diabetes

In the hot zone, people who didn’t think they had sugar get diagnosed with full-blown diabetes all the time. A bit of blood and some sweat could change that trend.

The CDC strategy is to identify people most at risk for developing diabetes and provide in-person coaches to work with them on eating better and exercising more. Weekly sessions wind down to monthly ones over the course of a year.

Finding those most at risk requires a simple blood test to check glucose levels. A normal level is below 100, and a diabetic level is over 125. People whose blood sugars test in between those numbers are considered prediabetic.

A government study showed that prediabetics who lose 5 percent to 7 percent of their body weight reduce their risk of developing diabetes by 58 percent.

The CDC-led National Diabetes Prevention Program has yet to make an impact in Nashville’s hot zone. The national YMCA has partnered with the CDC in the program, but the Nashville Y has not signed up.

Ted Cornelius, vice president of health innovation for the local Y, said he’s in conversations about joining. But such an intensive program would require financial support. It costs between $300 and $400 per person a year — significantly less than treating a diabetic, but still more than the Y can budget.

The Matthew Walker Comprehensive Health Center does offer CDC-recognized lifestyle classes for diabetes prevention, but community health centers like it and United Neighborhood Health Services cannot stem the epidemic by themselves.

In Nashville’s inner city, there are lots of locations to get food — even fresh produce — but in too many places the food is canned with sodium, fried in grease or loaded with sugar. The neighborhoods may not be in a food desert, where there’s a scarcity of grocery stores, but they are in food swamps, where there’s a fried chicken outlet, pizza restaurant or convenience store peddling junk food on every corner.

Managing the disease

Lynn Stuart, director of teen services for United Neighborhood Health Services, met Deonta through the program for overweight teenagers.

“He’s a little special,” Stuart said. “I had made home visits with him and found out that his grandmother was diabetic. That put a whole other spin on things as far as making sure that he had the skills that he needed to not only help his grandmother but to help himself.”

Stuart bought Deonta a blender so that he could mix fruit smoothies in the mornings instead of grabbing a prepackaged breakfast pastry.

Deonta was among 40 youths who took part in Teen Choice, which was funded by a grant from the Tennessee Department of Health. Stuart coached them on self-esteem, provided low-calorie dinners, coaxed them into fun exercise activities and took them on healthy shopping excursions to grocery stores.

“What we wanted to do more of was educate the parents,” Stuart said, noting that students reported on their diet logs having consumed Pop-Tarts, potato chips and soft drinks during weekends.

Teen Choice, which has now ended, sought to prevent obesity-related diseases. Mary Bufwack, head of United Neighborhood Health Services, said it was an expensive program to keep running without grant support.

Another program is aimed at helping people already diagnosed with diabetes better manage the disease.

United Neighborhood Health Services increased its diabetes counseling staff from one member to a team of three, consisting of a social worker, nutritional counselor and physical activity coordinator. The team worked with 284 diabetes patients from July to December. Of that number, 72 percent improved either their blood pressure, cholesterol count or glucose level.

This year, the organization is expanding its clinic at 905 Main St. in East Nashville to add a multi-service diabetes center — a space for people to learn together and share experiences, Bufwack said.

“What you are doing is creating a culture,” she said. “Cultures take groups of people.”

Coaching and caring

Even though the funding ran its course for the Teen Choice program, Deonta’s counselor stayed in contact with him. He listened this summer as Deonta talked about the loss of his uncle. He gently cautioned the young man against letting grief paralyze him and reminded him of the goals he had set for himself.

Deonta did not go into hiding in his room. His senior year, he made the Maplewood High School football team for the first time.

“I found out more about how much strength I had,” he said. “It gave me initiative to get stronger.”

Prodded by Deonta, Diaz also has worked at staying healthy. She’s tried to watch her diet, even during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays, and is now down to one insulin shot a day instead of three.

She has a ways to go. Blood sugar readings that used to go up to 400 and higher, she said, are now running around 300 or lower, which is still too high.

On a January afternoon, Deonta came home from school to find his grandmother, who walks with a cane and has osteoporosis, mopping the kitchen floor from the safe perch of a dining chair.

He took over the mopping, told her he had a bit of good news and shared how he had found an organization that would help him with college application fees.

Deonta is not the type of student who will ace an ACT on the first try, but he is the type who will catch a city bus repeatedly for the long ride to the testing site to take the exam again.

When he looks out the window at the passing streetscape, he watches “for rent” signs at houses in better neighborhoods and dreams about going to college.

“My uncle’s death was the first time I realized about actual death. It hurt,” Deonta said.

He’s determined to get out of the diabetes hot zone sooner or later.

This story was originally published in The Tennesean on January 20, 2013

Photo Credit: Larry McCormack / The Tennessean