When jail becomes a death sentence

This article was produced as a project for the California Data Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Disability agency blasts Sonoma County jail’s treatment of mentally ill

Two deaths in one jail in one month: How are we treating mentally ill inmates?

Rochelle Nishimoto recounts the death of her son Jason with her other son Adrian. (Lisa Pickoff-White/KQED)

In life, San Diego County residents Heron Moriarty and Jason Nishimoto never crossed paths.

In death, they became brothers of a sort. Both took their own lives after suffering acute episodes of mental illness. Both died before ever making a court appearance. Relatives say both men shared one more common bond: that jail officials didn’t respond to repeated warnings that the men were desperately ill and in danger of suicide.

The Moriarty and Heron cases are just two among more than two dozen San Diego County jail suicides between 2010 and 2015, a string of deaths that significantly exceeds the number seen in other counties. Statewide in 2015, one in four inmates who died in county jails took their own lives. But in San Diego County, half of deaths were from inmates taking their own lives. The deaths have prompted a series of lawsuits against the county and its Sheriff’s Department, which runs the jails, and has raised questions about whether the county is doing enough to stop seriously mentally ill inmates from harming themselves.

The San Diego County suicides also shed light on a national problem: the increasing number of mentally ill people landing in jails.

In California, the problem is compounded by what amounts to a massive statewide experiment: the transfer of thousands of inmates, some of them suffering from serious psychiatric disorders, from state prisons to county jails. Many of the local lockups have been unprepared to deal with the arrival of often seriously afflicted prisoners. At the same time, state hospitals that might treat prisoners are overcrowded, leaving mentally ill inmates languishing in jails with inadequate treatment facilities.

Heron Moriarty did not have long to understand the ins and outs of living with mental illness. Until this past spring, his family knew him as an energetic and religious family man.

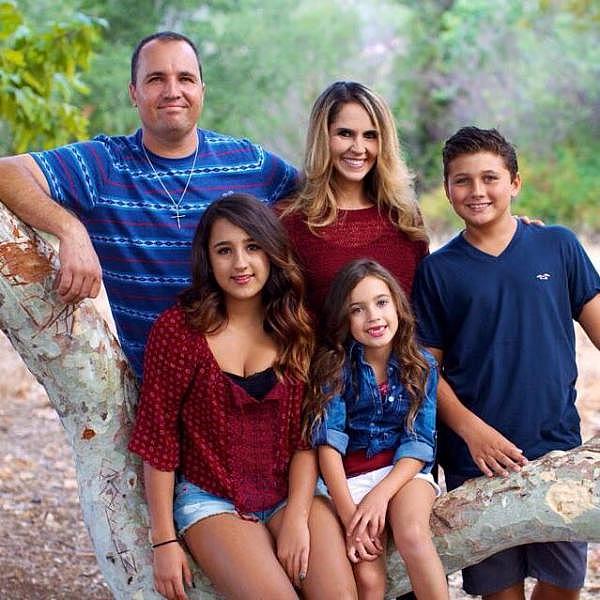

Heron and Michelle Moriarty with their three children in a photo taken before his death. (Courtesy the Moriarty family)

An electrical contractor, Moriarty often awoke at 2 in the morning to keep up with business. He and his wife, Michelle, met in a church singles group in the late 1990s and had three children. The family was actively involved in their evangelical Christian church, where Moriarty mentored others.

Then, in April, things changed.

“He started acting strangely, and talking in circles and not making any sense,” Michelle Moriarty says. The family took him to an emergency room and then to a psychiatric hospital where he was diagnosed as bipolar and manic with psychosis.

He got worse. He refused medications because he believed his illness was a gift from God. He called himself a prophet and said the Lord had commanded him to sacrifice his children. He said he was willing to do it.

Michelle Moriarty says she took the kids and moved out. Shortly afterward, on May 25, 2016, Heron Moriarty was arrested after throwing a rock through the front window of his brother’s home and smashing his truck into several cars.

“When they arrested him, I was relieved,” Michelle Moriarty says. “I thought, ‘He’s going to get the help he needs.’”

Heron Moriarty was jailed in the Vista Detention Facility in northern San Diego County. His wife says she called, faxed and emailed jail staff several times a day to tell them about her husband’s illness and medications. She spoke to a chaplain, she faxed a report from a Psychiatric Emergency Response Team officer who had arrested Heron three weeks earlier and sent him to a hospital for treatment. All told, Michelle Moriarty says she called the Sheriff’s Department 28 times in six days.

“I was telling them I was scared for his life the whole time. And they told me not to worry, that he was in good hands,” Michelle Moriarty says.

Despite the warnings, Heron Moriarty was neither placed on suicide watch nor seen by a psychiatrist. On the sixth day he was there, May 31, jail staff found him dead in his cell, with a T-shirt pulled tight around his neck and another shirt stuffed in his mouth.

“My husband shouldn’t have had two shirts to be able to do that to himself,” Michelle Moriarty says. “You know, he should have had paper clothes or no clothes or something after me warning them day after day.”

For more than two decades, Jason Nishimoto and his family managed his schizophrenia. He worked as a welder refitting plumbing pipes on Navy ships. He loved to write short stories and poems.

But last year, Nishimoto started experiencing side effects from his psychiatric medications, leaving him depressed and prompting several suicide attempts.

Then on Sept. 24, Nishimoto tried to kill himself by taking a full bottle of an anti-seizure drug. The overdose made him manic. Jason’s brother Adrian took his car keys away and called 911.

Jason Nishimoto (left) on the beach with family and friends. (Courtesy the Nishimoto family)

Jason responded by grabbing a garden shovel and threatening Adrian, who tackled him.

“He was like the drunkest man you’ve ever seen,” Adrian Nishimoto says. “So his attempts were not in any way going to hurt me. I was egging him on, to get him to do that so he would stay here. … I just wanted to keep him in this area until the police showed up.”

The next morning, a psychiatric nurse at Vista Detention Facility called Jason’s mother, Rochelle Nishimoto, to ask about his current medications because he was too incoherent to answer her questions. It was the first time the family realized that Jason had been jailed and not hospitalized.

The last thing the psychiatric nurse said was, “Don’t worry, mom, we’ll take care of him,” Rochelle says.

On his fourth night in jail, the evening before he was scheduled to see a psychiatrist, Jason Nishimoto hanged himself with a bedsheet.

“They blatantly ignored their own policies,” Rochelle Nishimoto says. “I’m a registered nurse. Any time that we would have a patient or resident that was suicidal, I know what 15-minute watches are, suicidal precautions. Any nursing home, any hospital that does not follow those — they would be hit with the biggest fine. People would be fired. It would not be tolerated. Period.”

Earlier this month, Rochelle Nishimoto sued the the county and Sheriff’s Department for Jason’s death in federal court for wrongful death and violation of civil rights. She says it’s the only way to prevent more deaths.

“It would be much easier — less emotional — for me to let it go. But then this stubborn streak comes up and says, ‘How dare they neglect my son? How dare they?’” she says, pounding her kitchen table.

The Citizens’ Law Enforcement Review Board, an independent board, is still investigating Jason Nishimoto’s and Heron Moriarty’s deaths.

One of the striking aspects of the suicides of Jason Nishimoto and Heron Moriarty is that they occurred after the high number of deaths in San Diego County’s jails had received widespread public attention. They also followed the jails’ adoption of new procedures designed to identify at-risk inmates and stop them from killing themselves.

County officials, including the medical examiner’s officer, the Citizens’ Law Enforcement Review Board and county Board of Supervisors declined to be interviewed for this story, referring us to the Sheriff’s Department.

Sheriff’s spokeswoman Jan Caldwell ultimately responded to numerous requests for comment by telling us the department was “unable to participate.”

But public records requests and local reporting shed light on the Sheriff’s Department’s response to the deaths behind bars.

In San Diego, a registered nurse screens inmates for medical and mental health problems during booking. This determines whether an inmate will be placed in a psychiatric unit, a special cell for suicidal inmates, a single cell or in general population. Medication orders are placed, and medical or psychiatric visits scheduled.

Neither Heron Moriarty nor Jason Nishimoto was placed on suicide watch or given close examination when they were booked. Jail staff isolated both men, placing them in cells, alone, for up to 23 hours a day.

Terry Kupers, an East Bay psychiatrist and expert on the treatment of mentally ill patients in jails and prisons, says it’s common for mentally ill people to be segregated from the general population.

“The sheriff doesn’t mean it as a punitive measure. He’s just doing it to protect the inmate. But then you’re isolating someone with a serious mental illness, and that’s the worst thing for his treatment and his prognosis,” Kupers says.

The continuation of medication is also imperative. Jason Nishimoto did not receive any of his medications while in jail, Rochelle Nishimoto says. A psychiatric nurse told Rochelle that Jason’s medication was “too expensive.”

Jails determine what medications they will and won’t give inmates, but Kupers says the institutions’ medication lists are often inadequate for effective treatment.

“The newer medications are on patent, and they are more expensive. So the jails don’t tend to prescribe them, and it makes a lot of difference what medication you’re on,” Kupers says.

Being taken off some psychiatric medications suddenly is dangerous and can cause suicidal thoughts and medical problems.

Both Moriarty and Nishimoto also experienced another common problem during their brief stays at the Vista jail. The facility does not have an on-site psychiatrist. Instead, the county uses several psychiatrists who shuttle from jail to jail. This kind of delay to see a psychiatrist is very common in jails throughout California, and dangerous, says Kupers.

“So if someone comes in on a Saturday night and they’re very psychotic, and the psychiatrist comes in on Thursday, they will have no psychiatric attention between Saturday night and Thursday, and … they’re going to be very disturbed,” Kupers says.

In 2015, nearly one-third of the 4,980 or so inmates in San Diego County jails on any given day were receiving some form of mental health care.

Even when inmates receive therapy, it is far from what most people would think of as a normal session. Therapy in most county jails, including San Diego’s, is predominantly conducted through a food slot. Cellmates, guards and others can easily listen in. Experts like Kupers say that this kind of therapy is common — and inadequate.

Lydia Nunez holds a photo of her son Ruben. (Lisa Pickoff-White/KQED)

Lydia Nunez’s son Ruben — a 46-year-old, homeless schizophrenic — died in San Diego Central Jail almost exactly a year ago. She says the death tore a huge hole in her life.

“He always said he loved me,” she says. “There was a never a day where he wouldn’t stop saying that. So at this point, I miss him saying that to me.”

Ruben Nunez had suffered from severe mental illness his entire adult life, but the path that led to his death in the Central Jail began in March 2014, when he was arrested on felony assault charges for allegedly pitching a rock through a car window. His mental illness was so crippling that he was judged incompetent to stand trial and sent to Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino for treatment. He refused to take psychotropic drugs prescribed by doctors there, so he was medicated involuntarily.

Schizophrenia was far from Nunez’s only problem, doctors at Patton observed. They noted that he showed signs of psychogenic water intoxication, a complication of a psychiatric condition that made him want to drink massive volumes of water. Unchecked, the condition can be fatal.

Because Nunez was said to have been “drinking water in dangerous amounts,” doctors at Patton required him to be monitored closely to ensure he didn’t consume excessive amounts. Without that monitoring and other treatment, a Patton doctor wrote, Nunez’s water intake “could easily have killed him.”

That was Nunez’s state immediately before Patton State Hospital sent him to San Diego Central Jail last August to await a court hearing that would determine whether doctors could continue his involuntary medication.

Exactly what Central Jail staff knew about Nunez’s condition when he arrived on Aug. 8, 2015, isn’t clear. What is evident from medical examiner’s documents is that he was placed in a cell with a toilet and sink, meaning he had free access to water.

A federal lawsuit filed in June 2016 on behalf of Lydia Nunez alleges that the jail’s failure to limit Nunez water intake proved fatal.

Early the morning of Aug. 13, a guard found Nunez vomiting in his cell. A nurse visited shortly afterward to administer Nunez’s regular medications. Then Nunez was left alone. Less than an hour later, he was found unresponsive, covered in vomit and urine. Attempts to revive him failed, and Nunez was pronounced dead.

An autopsy found he died of complications of water intoxication. How much water would it have taken to kill him? The medical examiner’s report on the death remarked that “the quantity of water necessary for this condition is around 6 liters ingested in a short time.”

The Nunez lawsuit alleges that failures by both Patton State Hospital and Central Jail staff led to the death.

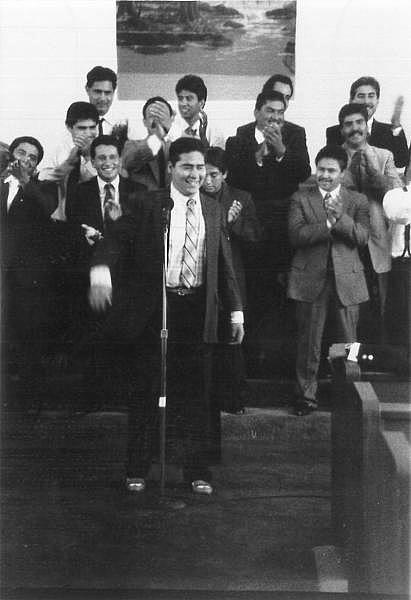

Ruben Nunez sings at a church in National City in 1990. (Courtesy the Nunez family)

The complaint accuses Patton of failing to send the jail a specific alert about Nunez’s water disorder, a document that should have spelled out strict protocols for monitoring the condition.

The suit also alleges that jail staff ignored medical records showing that Nunez was at risk for water intoxication, then failed to act when he showed signs of being in severe distress.

The October 2015 medical examiner’s report on Nunez’s death notes that an investigator had obtained medical records through the San Diego Sheriff’s Department showing that the inmate “had a history of schizophrenia and hyponatremia, which required water restriction.“ (Hyponatremia is a potentially fatal condition marked by critically low sodium levels in the blood. The condition is most often caused by overconsumption of water.)

The lawsuit alleges that Nunez’s death is part of a long history characterized by the Sheriff’s Department’s “systemic failure” to provide adequate health care for inmates coupled with a wider failure by the county “to investigate incidents of medical neglect, staff misconduct and deaths in the jail.”

As with the Moriarty and Nishimoto deaths, the Sheriff’s Department declined to discuss the Nunez case.

For Lydia Nunez, though, the condition of her son as he died — on the floor of his cell, in jail clothing soaked with vomit and urine — speaks volumes.

“They just didn’t care about this person. This person that was just there, just lying there unconscious,” Lydia Nunez says. “I felt like they just ignored him.”

One of the many questions hanging over these deaths and others in the San Diego County jails is whether they’ve been adequately investigated.

That question emerged as a central factor in the case of Bernard Victorianne, a 28-year-old man who died in his county jail cell in September 2012.

Victorianne swallowed a baggie of methamphetamine as he was arrested for driving under the influence. A wrongful death lawsuit filed against the sheriff department said Victorianne “was in distress for days, screaming and telling staff that his insides were ‘on fire.'”

CLERB’s inquiry into Victorianne’s death found that correctional and medical staff failed to take basic steps to respond to Victorianne’s situation or to investigate his death.

Julia Yoo, the attorney who sued on behalf of Victorianne’s family, said the county has agreed to settle the case for $2.3 million.

That’s just the latest in a series of expensive verdicts and settlements arising from inmate deaths. In 2014, a federal jury awarded $3 million to the parents of Daniel Sisson, a 21-year-old inmate who died in the Vista Detention Facility in 2011. Sisson was left untreated after he suffered an asthma attack while experiencing drug withdrawal.

The county also settled with the family of Tommy Tucker, a schizophrenic inmate who died at the Central Jail in 2009. Jail video shows that Tucker tried to get a cup of water back to his cell during a lockdown. It is unclear whether Tucker heard or understood the guards’ instructions to put the cup down. Jail guards rushed Tucker, using pepper spray, a chokehold and a spit sock to subdue him. Tucker died of asphyxiation during the hold.

CLERB did not investigate Tucker’s death. However, during trial it emerged that sheriff’s deputies reviewed the video together before writing reports about the death or being interviewed as part of the death investigation.

This winter, the review board suggested that the department stop allowing officers to review video footage before writing incident reports as part of their recommendations around body camera footage.

“In theory, what should happen is when there’s an unfortunate death there should be a serious investigation. And whatever can be found that led up to the death should be changed. That process is not very active in California,” psychiatrist Terry Kupers says.

There are currently about 8 more wrongful death suits against San Diego County.

“It needs to stop right here, now,” Lydia Nunez says. “People are dying in the county jail and nobody’s doing anything about it.”

Nicole West and Alexander Cwalinski contributed to this report.