Dr. Norman Guthkelch, Still on the Medical Frontier

Dr. A. Norman Guthkelch

At 97, retired pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Norman Guthkelch has ridden more than one wave of change in the practice of medicine.

He remembers that his mentor Sir Geoffrey Jefferson, for example, Britain's first professor of neurosurgery, cautioned his students against relying too heavily on x-rays. Jefferson would warn, "The eye has rested upon the evidence of fracture, and the mind has traveled no further."

"X-rays created a meaningless distinction between 'fractured skull' and 'no fracture,'" Guthkelch explains, "whereas the important thing is the degree of damage to the underlying brain."

"That time gave me an advantage over surgeons with no battle experience," he reflects. "I'd seen enough blood. Operating for its own sake was not an attraction."

One of his observations was that children in neurological distress were sometimes suffering the effects of subdural hematoma—that is, blood underneath the dura mater, the tough but flexible membrane that lines the interior of the skull. A subdural hematoma does not invade the brain, but it can exert dangerous pressure on the tissues below. And while a pool of subdural blood may dissolve on its own, it may also expand, causing further problems.

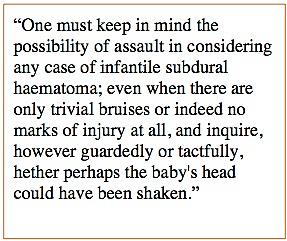

Guthkelch published his first paper on pediatric subdural hematoma in 1953, when he wrote in the British Medical Journal:

"It should be emphasized that infantile subdural effusion is not a rare condition. Study of the records of the Royal Manchester Children's Hospital for the four years covered by this series shows that, of all surgical conditions of the central nervous system occurring in the first two years of life, only spina bifida and hydrocephalus were seen more often than subdural haematoma... Similarly, Smith and her co-workers (1951) have reported finding subdural effusions in almost a half of their cases of bacterial meningitis in infancy, and Everley Jones's (1952) figures are similar."

At that time, before CAT scans or MRIs, doctors inferred the presence of subdurals in living patients from the symptoms: convulsions, vomiting, and headaches in adults or fussiness in babies. The only way to confirm a subdural hematoma was to penetrate the subdural space. With an infant, the surgeon could pass a needle between the unfused plates of the immature skull. A problematic pool could then be drained, slowly, over several days to avoid a sudden change in pressure. In his 1953 paper Guthkelch described the procedure developed by pioneering pediatric neurosurgeon Franc Ingreham at the Children's Hospital Boston, and reported on his own findings while treating 24 cases.

The paper that brought Guthkelch into the shaken baby arena is the advice he offered in the May 22, 1971, issue of the British Medical Journal under the title, "Infantile Subdural Haematoma and Its Relationship to Whiplash Injury." At that time in Britain, Guthkelch says, shaking a child in the course of discipline, "or not even discipline, correction, shall we say," was considered acceptable. He recommended that health workers discourage the habit, as it was causing damage to developing brains. He cited cases in which parents had told him of shaking their child, and he referenced a paper by U.S. radiologist John Caffey, who had noted the combination of subdural hematoma and long-bone fractures in a few very young children. Guthkelch's paper on shaking aroused not much interest in England, he recalls. He mailed a copy to Dr. Caffey at his hospital in Pennsylvania and began his own local education campaign. "My great allies in this were the case workers, who were a tremendous resource," he recalls. "They were usually trained nurses, whom the health system would pay to make rounds in economically depressed areas."

But he had an obvious back-up plan: The States. His mother had a close friend in Philadelphia, and he'd been brought up on on Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. He accepted an invitation to the Pittsburgh Children's Hospital, where he reports feeling immediately at home. "You Americans are very lovable people," he grins.

He was surprised, however, to realize that his colleagues were diagnosing a condition known as "Caffey's syndrome," believed to result from violent shaking of an infant. Caffey's paper on infant shaking, published in the U.S. a year after Guthkelch's in Britain, had enjoyed far greater circulation, and few had noticed the footnote citing Guthkelch's original paper. "No one was asking me about it, and I didn't really have anything further to say about it," Guthkelch shrugs.

He stayed in the field until 1992, as improvements in medical imaging and surgical technique transformed the way doctors diagnose and treat problems of the brain. Neurosurgeons were collaborating with radiologists as they honed their abilities to decipher the lights and shadows of CT scans and MRIs. "I loved every minute of it," he beams.

He'd intended to retire in the 1980s, when he left Pittsburg Children's and moved with his wife to Tucson, Arizona. The local university hospital, however, asked him to take on a temporary position at the neurosurgery unit, where he remained for another eight years. Then he finally found time to work on his translation of the New Testament from the Greek, to organize a lifetime of bird photographs, and to spend more time with his wife as her health began to fail.

Sperling says she was electrified to learn that the grandfather of shaken baby theory lived two hours south of her. She and her students were convinced that Witt was innocent: His son Steven had suffered a short lifetime of serious health problems, including hospitalization for seizures that were never explained, not even fully controlled with medication. Sperling was was unsure of the reception she would receive from Dr. Guthkelch, "but he turned out to be an amazing man," she says, "an amazing, gracious man."

"It was Carrie who opened my eyes to how much of this is going on," Guthkelch sighs.

He says he never intended that the presence of subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhages, with or without encephalopathy, should prove that a child had been shaken, only that shaking was one possible cause of the bleeding. "I am frankly quite disturbed that what I intended as a friendly suggestion for avoiding injury to children has become an excuse for imprisoning innocent parents."

Sperling suggested he read law professor Deborah Tuerkheimer's 2009 law-journal article on how shaken baby syndrome is handled in the courtroom. "She certainly nailed it," he says of Tuerkheimer's work. Some months later he saw some "harsh, unprofessionally harsh" criticism of that paper. When he tried to talk about it with people he knew from the child-protection community, he realized how wide the schism was. "There are cases where people on both sides, both of whom I admire equally, are barely able to speak to one another," he told NPR.

He contacted Tuerkheimer, and the two of them hit it off. They speak regularly on the phone, he reports, and "we find we are of one mind on this subject."

After his wife's death, Guthkelch moved to a suburb outside of Chicago, where he's continued trying to be an ambassador between the two sides. When he learned that journalism students at the nearby Medill Justice Project had taken on a shaken baby case, he reached out to them. One result is a first-rate podcast that includes interviews with both him and Dr. Robert Block, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

When Dr. Sandeep Narang, pediatrician and attorney, published an argument that courtroom testimony about child abuse is best left to trained child-protection physicians, not paid experts, Guthkelch wrote the introduction to a rebuttal by a team of advocates for the innocent accused. (For a quick summary of Narang's article and Guthkelch's response, see this page.)

Guthkelch also spends what time he can reviewing cases. "Let me be quite frank," he says, "For a 97-year-old I'm fairly well preserved, but my memory is not what it once was." Producing a medical report takes careful concentration and more double-checking, as does following and responding to the literature.

But he perseveres. "I want to do what I can to straighten this out before I die," he says, "even though I don't suppose I'll live to see the end of it."

Which reminds me of something Carrie Sperling said about him when I spoke with her at the Twelfth International Conference on Shaken Baby Syndrome/Abusive Head Trauma in the fall of 2012. "I felt a little bit bad about getting Norman Guthkelch involved, because I knew he would become controversial" she said in a video dispatch posted on the Medill site. "I did warn him, but I don't think there's any way to warn people of how the wrath can come down on you when you get involved in this sort of thing. But in the end, everyone I've talked to who's talked to Dr. Guthkelch... It's amazing the effect he's had on the experts I know, on the people I know. I'm hoping that he lives a long, long time so that he can meet with as many people as want to meet with him and talk to as many people as want to talk with him."

copyright 2013, Sue Luttner

If you are not familiar with the debate surrounding shaken baby syndrome, please see the home page of my site on the subject at http://onsbs.com/