Unraveling the Global Epidemic of Misinformation about Fertility Treatments

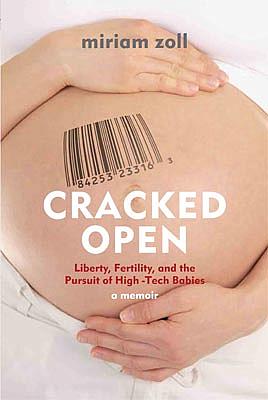

In writing my book -- Cracked Open: Liberty, Fertility and the Pursuit of High-Tech Babies -- I wanted to reveal the hidden side of treatments, and to caution women intent on birthing babies to avoid making the same irrevocable decisions so many educated, middle-class women in Gen-I.V.F. made when we delayed childbearing (see first blog post here). There’s a global epidemic of misinformation about the age when women’s fertility naturally declines and about the power of modern medicine to reverse this. Here’s what I learned through the process.

1. You Will Probably Be Physically and Emotionally Traumatized. I found that the side-effects of the drugs, the constant prodding and probing below my hips, and the repeated failures, miscarriage, and devastatingly dashed hopes brought me to the point where I sought treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (P.T.S.D.).

A study by Allyson Bradow, Primary and Secondary Infertility and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, confirms that women who experience failed fertility treatments often exhibit symptoms of P.T.S.D. Close to 50 percent of 142 participants in Bradow’s study met the official criteria for the disorder; that’s about six times higher than its prevalence in the general population.

Those of us who bump into age-related infertility end up confronting two tragedies: the loss of our deep primal desire to birth a baby and the realization that we guzzled the Kool-Aid: we built our entire “women-can-finally-have-it-all” adult life on an illusion.

2. Your Sexuality Will No Longer Belong to You. In order to endure the physical and emotional strain of multiple I.V.F. cycles, you will eventually detach from your body and your sex drive. This is almost inevitable, as the doctors will control, through drugs and technology, what used to be controlled by Nature.

By the time I reached The Donor Egg Phase, sex equaled stress. It meant needles and Petri dishes, stirrups and vaginal probes. It was associated with disappointment and guilt and pain. Most nights I cried myself to sleep.

3. You Will Blame Yourself. In 2012, the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology reporte

In my case, as cycle after cycle failed, I buried myself in a tomb of self-blame so disabling that I was unable to work for one full year. It was my fault my ovaries weren’t producing enough quality eggs. It was my fault we waited too long. It was my fault we had a miscarriage. I was an expert when it came to contraception, but I was embarrassed about my ignorance regarding reproduction and angry with myself for how blindly I entrusted doctors to work their magic in a laboratory.

4. The Absence of the Sacred Will Deplete You. Fertility clinics and their staff are focused on manufacturing embryos, not on counseling patients compassionately after miscarriages, stillbirths and negative pregnancy tests. I often wondered what the doctors and nurses thought about me, the human being, as I lay on the gurney, and when I eagerly signed up for another cycle only days after my miscarriage. Did they feel sorry for my desperation, which kept them employed? Hooked into stirrups, did I have a face, a husband and a life, or was I just another older woman trying to have a kid?

A few months after our second donor was diagnosed as being infertile, we finally, for the first time, sat in a room with other couples in the same situation. A minister’s wife told the tale of how she’d adopted four children whose mother could no longer care for them.

Only minutes into her story, the dam inside of me broke loose and a river of tears began streaming down my face. This was the first occasion since we’d begun the arduous baby-making process that we were communing with people who actually talked about the sacredness of the path toward parenthood. Never once during treatments had clinic staff even mentioned the beauty or spirituality of creating and stewarding new life.

5. Treatments Involve Health Risks. In a branch of medicine that is still very much experimental, I injected into my body whatever drugs the doctors thought might help me become pregnant. I am an educated woman, a researcher and writer by trade, a feminist, and yet I became an obedient guinea pig.

When I finally stopped treatments and was invited to join the board of Our Bodies Ourselves, I learned that there is scant evidence-based research about the long-term effects of treatments on women’s and infants’ health. Existing data does show an increased risk between certain fertility interventions and breast, ovarian and endometrial cancers, among other side effects, and a 26 percent increased risk of birth defects in I.V.F. babies. The common practice of implanting multiple embryos is known to pose serious health risks to mothers and infants, including pre-term delivery, low birth weights and costly hospitalizations.

The effect of treatments on egg donors has been even less studied, yet we do know that side effects can include blood clotting, infertility, and ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome, and in some rare instances, death. Potent drug regimens can create as many as 30 to 60 eggs in one cycle, as opposed to the solo egg a woman naturally produces during her period. (You can learn more in the film Eggsploitation and from the group We Are Egg Donors.)

On the positive side, there is now the Infertility Family Research Registry (ifrr-registry.org) that invites women going through A.R.T. to submit information about their health and that of any offspring. Of the roughly 500 clinics in the U.S., however, fewer than 100 have signed up to promote it.

6. Treatments Costs a Fortune. Be Prepared to Confront Your Privilege. One average I.V.F. cycle in the United States costs between $12K and $15K; a donor-egg cycle, $30K; and surrogacy anywhere from $75K to $150K. Around the globe, the greatest cause of infertility is untreated sexually transmitted diseases; these hit poor women the hardest. Needless to say, fertility treatments are largely unavailable to them.

Only 15 U.S. states offer insurance policies that cover fertility procedures, compared to Britain, Israel and many countries in Europe that subsidize some citizens’ fertility treatments. In Sweden, France and Italy, single women, and lesbians and gay men, are often barred from accessing them at all.

7. Fertility Clinics Are Big Business. Most clinic staff wear two incompatible hats: a medical one and a business one, so this means their advice might include steering you towards trying new technologies and drugs. Our reproductive endocrinologist told us honestly that our chances of I.V.F. success were low, but he also said, “It only takes one good egg to make a baby.” Michael and I were awash in yearning and denial; the doctor knew that. “New techniques and protocols are constantly being developed,” he said. “You just never know what can happen.”

The world’s first fertility company, Virtus Health, went public this year to the tune of almost half a billion dollars. Its CEO is quelling investors’ fears that improvements in A.R.T. might mean fewer cycles for clients. Uh-oh — dwindling revenues.

8. Fertility Clinics Are a “Wild West.” There is only one piece of U.S. federal legislation, loosely enforced, that requires clinics to self-report their annual success rates: the 1992 Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act. Apart from this, the industry operates below the public radar.

Activities that are stunningly unregulated include: implanting multiple embryos that may increase rates of success but also endanger women’s and infants’ health; engineering and selling anonymous embryos in the marketplace; prescribing off-label drugs that have not been approved by the F.D.A. for fertility use; marketing donor embryos or donor egg treatments to post-menopausal women; and offering expensive procedures –– such as egg freezing — that have no proven track record in efficacy or safety.

9. Your Treatment Options May Exploit Poor Women. Patients wrestling with the pain of infertility and considering options like surrogacy and egg donation need to understand and connect the dots between their treatment choices and these women’s lives. Many surrogates, in India and elsewhere, are illiterate, extremely poor, and often not informed about what they’ve consented to. They can be separated from their children for up to a year, relegated to “surrogacy dormitories,” and, if their pregnancy fails, compensation and follow-up health care may be withheld. As health consumers, patients can plan an important role promoting greater health and human rights protections for all parties involved in reproductive technology treatments.

Commercial surrogacy and egg vending are booming businesses. As someone who has studied the link between poverty and gender, I would much rather see women and girls acquire economic security through better access to educational, constitutional human rights protections, and sustainable employment opportunities, not by a singular focus on their gonads and wombs.

10. You Will Dislike Yourself. Entering the world of A.R.T. will challenge you to reassess much of what you thought you knew about yourself. Long-held beliefs about right and wrong begin to flake off your psyche like old paint on a windblown house. Moral dilemmas about eugenics and cloning invade your dreams.

For me, deciding to use donor eggs was much more difficult than choosing I.V.F. I was averse to how unnatural it was, and I felt deep shame for my conspicuous conception, paying another woman to risk her health and possibly deplete her own egg reserves on my behalf. How and why do these young women decide to sell their eggs to someone like me? How does a donor agency determine that one woman’s eggs are worth $8,000, but another’s only $5,000? Blonde, svelte donors seem to get paid more than brunette, overweight ones. And Caucasian, Asian and African-American eggs carry very different price tags. Ivy League egg donors with high S.A.T. scores and 36-24-26 body measurements have been paid as much as $100,000 for their eggs.

While searching for a donor, Michael and I were aghast at how judgmental we became. This one’s eyes are too close together. I don’t like her teeth. She looks bi-polar. She looks uneducated.

Like any protective parent, you want to be discriminating when choosing the genetic code and physical traits of someone whose egg will form half the D.N.A. structure of your potential offspring; that’s understandable. Still, it did not sit well. And even though we are now, through adoption, the proud and grateful parents of the most delicious little four-year-old ever, our A.R.T. ordeal may have scarred us for life.

Image by jasoneppink via Flickr

A version of this post originally ran in Lilith magazine and has been used with permission.

Miriam Zoll is an award-winning writer and author of Cracked Open: Liberty, Fertility and the Pursuit of High-Tech Babies, founding co-producer of the Ms. Foundation for Women’s original “Take Our Daughters To Work Day,” and a board member of Our Bodies Ourselves and Voice Male Magazine.