Life is complicated in Indian country and so is health care

Imagine living in communities that defy social definition. This is Indian country, where our identification is usually stereotyped as sports mascots, grandparents raise their grandchildren and the annual household income isn't even in the same neighborhood as the national average.

I say quite modestly that Indian people are a sociological gold mine. We continue to have the highest incidence of virtually every social ill in America like suicide, unemployment or domestic violence. Yet we are so small of a minority that our statistical information is not broken down by the U.S. Census even though we are the first minority in this country.

Health wise, we continue to register sky high incidence of heart disease and confound health care providers by registering blood sugar levels that would put others in a coma. Most natives will laugh and light another cigarette or pop open another cold soda and a bag of Cheetos. I honestly cannot count the Indian friends, relatives and family members who have been felled by diabetes.

When I was considering my topic for my fellowship application, I had to bypass some options that were too narrow in focus. It was about that time that the national deadline for Obamacare was approaching. When I learned that Indians were the only group allowed to opt out of the federal plan, I knew synchronicity was pointing the way. I had to find out what the story was behind the national federal plan and whether a one-size-fits-all deal would fit Indian country.

I began doing legwork before I submitted my application. Not because of overconfidence but more like doing a reconnaissance screen of the territory. I was operating only on a hunch but I soon came away from an open Affordable Care Act (ACA) enrollment day convinced that this was a story that needed telling.

I will work a six-part series on Obamacare in Indian Country. Our lives are complicated by heritage, tradition and criss-crossed jurisdictions. Most Indians will probably opt out of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) because of money. The oft coveted Indian Health Services (IHS) is already available and despite a dearth of federal allocations, it is free to enrolled members of federally recognized tribes. But IHS' per capita cost for each patient trails other federally subsidized health care agencies. Age old treaty provisions bind us to IHS and vice-versa but we still play on an uneven playing field.

I plan to speak with Indian families (both on and off reservation) who enrolled in Obamacare to see what shaped their decisions. Next, I plan on visiting with tribal officials who work hard to improve health care in their communities. They know what works and what does not for the tribal citizens in their communities. Each community is different; what works for Apache may not work in Cherokee or in Choctaw and those in urban settings have to play by a whole different set of rules for health care.

Lastly, I will ask health policy analysts who have a foresight into whether Obamacare will work in Indian Country. Whether they sit on federal health boards or local urban Indian clinic boards, their insight guides Native peoples even when they're not aware of a steering wheel.

I honestly don't know what I will find as I work on this series. Whatever it is, of one thing I'm sure. It's bound to be complicated.

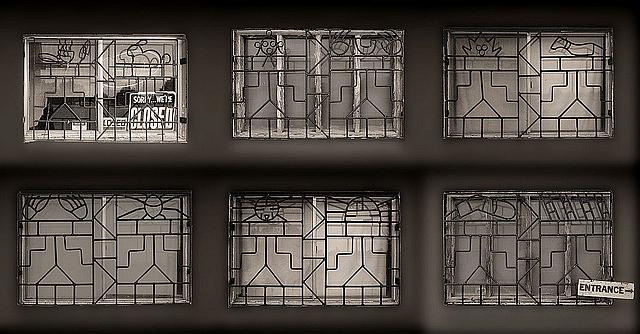

Photo by joiseyshowaa via Flickr.