COVID-19 keeps throwing up big data hurdles for reporters. What can be done?

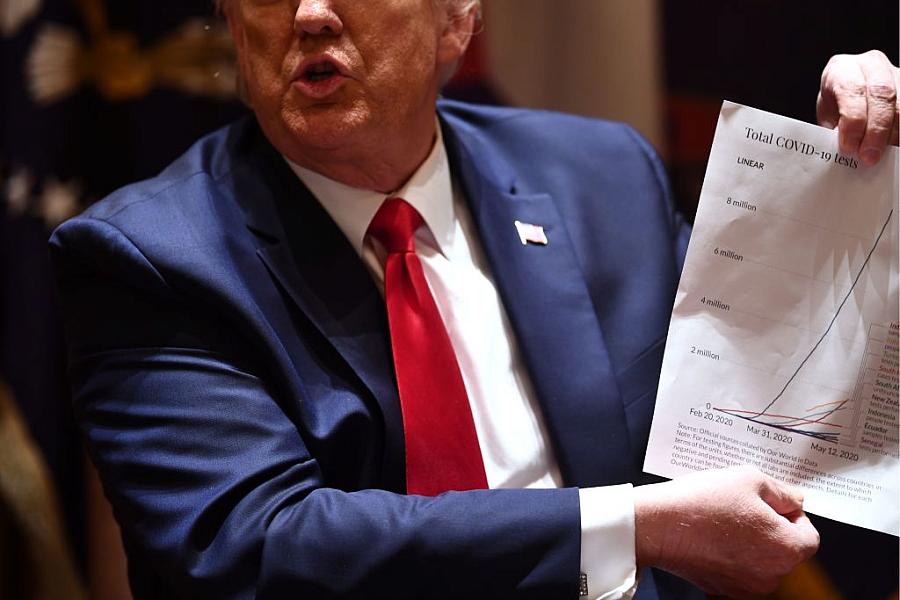

(Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP)

As part of its “You Asked, We Answered” series, the Center for Health Journalism has been asking journalists what questions they have about reporting on COVID-19. This week's question: “Beyond making decisions with incomplete data, there are growing accounts of suppression of public health data on COVID-19. What can journalists do to tackle that?” — Inquisitive in D.C.

When it comes to reporting on the coronavirus pandemic, data is — perhaps more than any news story ever — an integral component.

From case counts to death totals to hospital capacity, numbers have been used by government officials to shutter economies across the world and order people inside their homes in an attempt to save lives. Those same statistics have been crucial guides in the reopening effort.

But the quality and accuracy of the data has been spotty. Many state and local healthdepartments have declined to release site-specific numbers. Some government agencies have deliberately manipulated COVID-19 stats.

So how can reporters get around such hurdles and deliver precise information when those data points are often used, during a global disease outbreak, to make life-or-death decisions? And what do you do when the data isn’t there?

“First of all, report it,” said Al Tompkins, a senior faculty for broadcast and online journalism at the Poynter Institute. “You can’t allow a lack of data to stop you from reporting. Report what you don’t have and constantly pound on that.”

That public pressure, he said, could eventually force the government bureaus to capitulate. Nowadays, many news organizations simply can’t afford to take those agencies to court to force the release of records.

“You just keep asking: Why? Why? Why? Why? Why?” Tompkins said. “Teach the public that this data generally is available. They release this kind of data all the time.

“It ought to be on the state to tell us why it’s off limits. There should be a presumptionthat it’s an open record, not a closed record. The public has a need to know this data. It’s not just a morbid curiosity.”

He noted that solid data on the number of cases and deaths in nursing homes and prisons have been among the hardest to come by. “Why do we care? Why does it matter?” he said. “Because critically ill patients end up in your local hospital right next to your grandma.”

Data on the impact of COVID-19 on Native Americans has also been difficult to obtain, he said, in part because of the federal government’s seeming reluctance to intervene with that community.

And the military has also not released coronavirus statistics broken down by installations, he said, citing national security.

“Why does that matter?” he said. “Because by the hundreds of thousands, these people live and commingle with populations in all those communities.”

To get around some of these obstacles, he suggests one possible tactic. Reporters can get ambulance transport records to see where clusters of patients are coming from. Then start asking questions.

“A pandemic cries for more data, not less,” Tompkins said. “We are all stakeholders in this. When we don’t know where the threat is or who poses the threat or in which places things are going bad, rumors start filling the void.”

We want to hear your questions about covering COVID-19 — ask your question here!

Paul Overberg, a data reporter with the Wall Street Journal, said that in the face of incomplete data, reporters have to utilize other tools at their disposal.

“It’s a real jigsaw puzzle,” he said. “I don’t want to say it’s like a whodunit. But you have to use all kinds of traditional reporting skills: What do we know? What don’t we know? How do we not get ahead of our skis and say things we can’t really say, because the data’s not really there or it’s not there yet?”

He said a lot of COVID-19 data is “jury rigged” or “ad hoc.” For instance, some states weren’t reporting probable cases despite the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention asking them to. And some states were combining the results of diagnostic and antibody tests.

Site-specific data isn’t always available, though Overberg noted that most states now report the incidence of COVID-19 in congregate care facilities — places like nursing homes and assisted living centers. To figure out where other cases are happening, reporters could ask public health officials if there have been clusters — say, at meatpacking plants or jails — or if infections have been more spread out across the populace. Overberg reported recently on the impact of the virus on crowded family homes in rural areas.

Overberg has also focused lately on death certificates, which some states have been quicker than others to release electronically.

“With death certificates, there’s still a lot of argument: Are we underreporting or overreporting?” he said. “It’s pretty clear as the epidemic spreads and goes on over

time, we’re underreporting. There hasn’t been a mortality event in our country like this in a century.”

Amid the pandemic, many journalists are having to re-learn — or learn for the first time — what Overberg called Data Journalism 101: “Who collected the data? Why did they collect the data? How did they collect the data? What did they do with the data?”

“Nothing focuses the mind like a crisis,” he said. “It is giving a lot of journalists a crash course in numeracy, if not data journalism, and basically being more sophisticated about not just understanding data and simple math … but how to put the right words and context around it.”

He also suggests reporters check in regularly with their sources to make sure the ways in which the data is being collected and reported hasn’t changed.

“There’s no set way to do this,” he said. “Reporters just have to be really skeptical about every single number they get.”

James Alwine, a visiting professor of virology at the University of Arizona and emeritus professor at the University of Pennsylvania, noted that the governor of Arizona has just started to be more forthcoming with coronavirus statistics following reports that the state misled the public on data, amid pressure to reopen its economy.

But Arizona is now in the midst of a severe COVID-19 crisis, which experts like Alwine say may have been fueled in part by state officials playing fast and loose with coronavirus numbers. Florida and Georgia, two other states accused of manipulating data to reopen quicker, have also experienced surges in confirmed cases.

“The governor was saying we had more cases because we were doing more testing, but then the hospitals started reporting that their ICUs were filling up,” Alwine said.

Rather than taking state governments’ data as gospel, he suggests checking with local hospitals and schools of public health to make sure what they’re seeing matches the official numbers.

As he put it in a recent editorial in The Hill, written with colleague Felicia Goodrum Sterling: “COVID-19 data must be collected and released independently of politics. Data manipulation and suppression will only endanger us and our society further.”

**