How Neuroscience Can Help Us Treat Trafficked Youth

Lily Dayton reported this story with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the University of Southern California's Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Oree Freeman.

(Photo Credit: Lily Dayton)

"I didn't tell anyone for a long time," says Freeman, now a 22-year-old survivor advocate at Saving Innocence in Los Angeles. Instead, Freeman began acting out, misbehaving in school and fighting with peers. When she was sent to the school counselor for "bad" behavior, the counselor recognized signs of abuse and made a report to Child Protective Services.

Though her abuser went to jail, Freeman herself didn't receive treatment for her trauma. And she continued to act out. By the time she was 11 years old, she'd spent time in juvenile hall for assaulting a classmate. She was still on probation when her mother's boyfriend was released. When he returned to her home, she ran away.

After only two nights on the street, Freeman met a man who said he'd take care of her. Then he brought her to "the blade"—the boulevard in Los Angeles where men solicited sex—and he sold her body. This was her introduction to the life, in which she quickly became entrenched. When she was 12 years old, Freeman was branded with her exploiter's name tattooed on her neck.

Ten years later, Freeman sits on the front porch of her West Los Angeles home. Her dark brown hair shimmies down her back. Though her neck tattoo has been partially removed, a faint etching of blue ink remains: a battle scar. "You thought it was OK," she says, "you thought it was your choice, and you really didn't understand that somebody was taking advantage of you. I thought I was in love with this 35-year-old man."

Like Freeman, most commercially sexually exploited children have a history of trauma. Consistent with earlier research findings, a 2017 study of exploited youth in a specialized treatment program in Florida found that 86 percent had experienced sexual abuse prior to their exploitation. Almost all youths in the study—nearly 98 percent—had experienced multiple traumatic events involving their caregivers.

A common misconception is that these youths are choosing to engage in the commercial sex trade. But as recent advances in neuroimaging techniques help scientists unravel the myriad ways that trauma affects the brain, emerging evidence suggests that brain changes resulting from trauma could make young people more vulnerable to exploiters and less receptive to people trying to help. Rather than making a conscious decision to rebel, these kids are simply doing their best to survive, using the adaptive strategies that their brains developed in response to a perilous world.

Early Trauma Triggers Massive Brain Changes

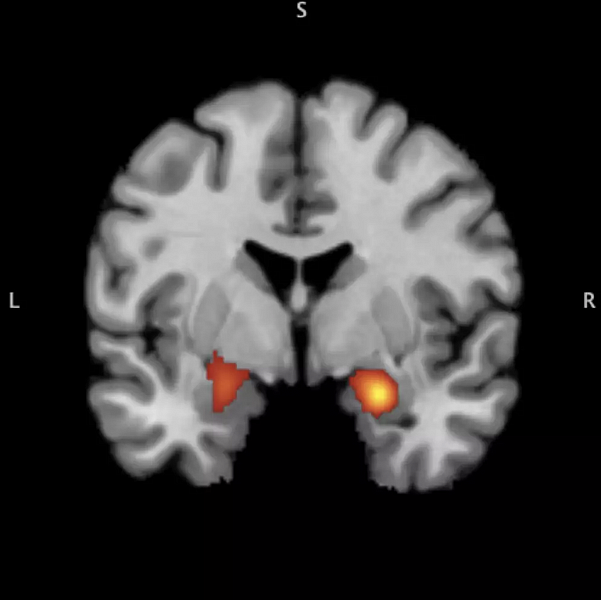

Though the human brain is adaptable throughout life, adaptability is greatest during childhood, as the developing brain responds to the surrounding environment. Survival is the brain's top priority. Young people growing up in dangerous environments will develop brains that are highly responsive to threat cues. In particular, recent studies show that children who have experienced trauma exhibit drastic changes in their amygdala, an area of the brain wired to identify signs of danger.

In the Stress and Development Laboratory at the University of Washington, Associate Professor of Psychology Katie McLaughlin uses neuroimaging to compare the brains of youth who have experienced trauma with those who haven't. Using fMRI, a technique for measuring brain activity, McLaughlin shows her subjects emotional images: pictures of people crying or displaying expressions of anger, sadness, or fear.

"In kids who have had trauma, their amygdala responds much more strongly to cues that could be potentially negative, and even cues that [others] might see as neutral," McLaughlin says. In other words, their amygdala casts a wide net, generating a strong emotional reaction even to cues that aren't necessarily threatening.

This overactive threat response can manifest in high levels of aggression or "acting out"—behaviors often seen in kids who have experienced trauma. Most kids victimized by commercial sexual exploitation have not only experienced trauma in early childhood, but also are repeatedly re-traumatized while they're exploited. Further, sex-trafficked youth are notoriously uncooperative with law enforcement, mistrusting of service providers, and presenting challenges for caregivers. But this isn't because they are inherently "bad" kids, McLaughlin explains; they are simply operating in survival mode.

Besides the amygdala, another brain region affected by trauma is the hippocampus, an area involved with contextual learning and memory. The hippocampus takes context into account, so that a person can appropriately respond to the same cues in different situations. For instance, most people would respond differently to hearing gunfire in a shooting range than they would to hearing gunfire in an airport.

McLaughlin's research shows that youth who have experienced trauma have a smaller hippocampus than those who haven't, and are less able to take context into account when they detect a threat cue. When McLaughlin presented images of faces embedded in real-world scenes to kids, those with a history of trauma exhibited less activity in their hippocampus while viewing angry facial expressions. And when given a memory test afterward, they were less able to remember scenes in which they'd identified people displaying anger.

"When those kids saw an angry face, it's almost like their attention was so narrowed, so focused on that angry face, that they weren't able to process the background context at all. They were only able to see that threat," McLaughlin says. People who can't take context into account, then, will have trouble discriminating between safe situations and dangerous ones.

Unraveling the Trauma Bond

Though the process of re-victimization is not well understood, it is a consistent pattern: Kids who experience trauma are more likely to be re-victimized, and to experience abusive relationships as adults. It may be that kids who are highly attuned to threat cues become habituated to their overactive alarm systems. "You just get used to having a strong emotional reaction, and it stops indicating [that you may have encountered] a bad person or a dangerous situation," McLaughlin explains.

But that's probably not the whole story, she says. The other component may involve humans' primal need for attachment. In order to survive, children form strong attachment bonds with their caregivers—even if caregivers are abusive. And when abused children grow up, they're often attracted to cues that link back to their trauma, a phenomenon known as trauma-bonding.

"People don't understand that their world is completely different from ours," Freeman says. "Basically, it becomes normal to you. You know, lying on your back 15 times a day—that's normal. Someone hits you and says they love you, that's normal. Because all this has happened since you were a kid, it's OK. Because that's what you're used to: Love hurts. Love, you get hit. Love is painful."

The mechanisms of trauma-bonding are not well known in humans, but rodent studies may offer some insight. Regina Sullivan, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the New York University School of Medicine, has conducted a series of experiments looking at how caregiver abuse affects infant brain development. Much as in humans, rats that have been abused as babies show overactive amygdalae. But when Sullivan presented adult rats with an odor that was paired with early abuse, the trauma-linked odor actually suppressed the amygdala, acting as an anti-depressant.

"When trauma occurs repeatedly with a caregiver, we think there's a co-activation of the fear system and the attachment system in the brain, and that produces a connection between the trauma cue and the attachment system," Sullivan says. These trauma cues that would normally activate the amygdala end up suppressing it, paradoxically creating a soothing effect.

In human studies looking at healthy attachments, a mother's presence will suppress activity in her child's amygdala, calming emotional reactivity. For adults, merely looking at photographs of a long-term romantic partner can suppress amygdala activity and decrease the perception of pain. Sullivan's research suggests that perhaps even when an attachment is abusive, the attachment figure can still suppress the amygdala. Thinking of the trauma-bond as a biological mechanism—rather than simply a "poor choice" a victim is making—may help in finding new approaches to intervention.

Treating Victims With A Trauma-Informed Approach

Because the brain remains malleable throughout life, it's never too late to mitigate the effects of trauma, McLaughlin says. There are a variety of evidence-based treatments that have proven effective in alleviating the mental-health consequences of trauma. For example, the technique of cognitive reappraisal, a cornerstone of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, can help victims better regulate their emotions by changing the way they view a distressing situation. They can try to imagine that the situation is occurring far away from them, or that they are viewing the event from a removed perspective, as though watching a movie screen. When McLaughlin taught such techniques to young people in her lab, they were able to decrease their emotional reactivity as well as their amygdala response to negative stimuli.

Though treating the long-term consequences of trauma is important, McLaughlin stresses the urgency of assessing and treating youth in the immediate aftermath of a traumatic event. "We need to start thinking about how to prevent the onset of mental-health problems [and] prevent re-victimization in kids who have experienced trauma—not just treating the problem once those patterns have already emerged."

The Yale Child Study Center developed a brief intervention, the Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention, that is designed to be used with children and their parents immediately after a traumatic event in order to increase coping skills and decrease rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In a small but encouraging 2011 pilot study, children that received the intervention were 65 percent less likely to exhibit PTSD at the three-month follow-up.

"What we really need to do is make sure that when people are encountering these children, they're doing everything they can to get them into evidence-based care," McLaughlin says. But the problem is often access: "We need to train more people in these approaches, [especially] people who are working in settings where kids with trauma are most likely to receive therapy," she says.

Meanwhile, one of the most important ways to help youth who've experienced trauma, including kids who have been commercially sexually exploited, is to view their treatment through a trauma-informed lens. Perhaps if someone had realized that her aggressive behavior at school stemmed from trauma, 11-year-old Freeman might have received support rather than detention. Perhaps if she'd received treatment once her sexual abuse came to the attention of authorities, she could have avoided forming a trauma-bond with her exploiter.

Freeman successfully extricated herself from her trafficker at age 15, after a staff member at her group home recognized signs that she was being exploited, and gave her the support and mentorship she needed. He started with a simple question: "Are you OK?"

"I had all these labels on me that I was this bad kid, hopeless, nowhere to go, foster youth, probation youth, this girl committing crimes," Freeman says. "Not one person had ever asked me if I was OK ... until I was 15 years old."

Because her mentor understood that Freeman's behavior stemmed from trauma, she says, he didn't give up on her. He supported her when she stayed in placement, and he supported her when she returned home after running away. He answered the phone when she called at 2 a.m. He helped connect her with services and with other mentors.

"I started to trust people," Freeman says. "This defense mechanism that I built for so long started to go down, and go down, and go down. And I embraced people. I allowed people in."

Today, Freeman still has triggers that stem from her trauma. But she also has coping skills—and a strong support system. As a survivor advocate, she mentors other sex-trafficking survivors.

"These kids are not hopeless," she says. "They may be broken, but they're not hopeless. They're amazing. You've just got to help them find the resilience within."

[This story was originally published by Pacific Standard.]