Measuring patient safety

Most hospitals around the country track and report complications of medical care. While many states make this information public, Oregon does not. That means that the best information about an individual hospital's quality and safety may be kept from the public. In this project, Betsy Cliff reports on the patient safety issues in Oregon health care systems.

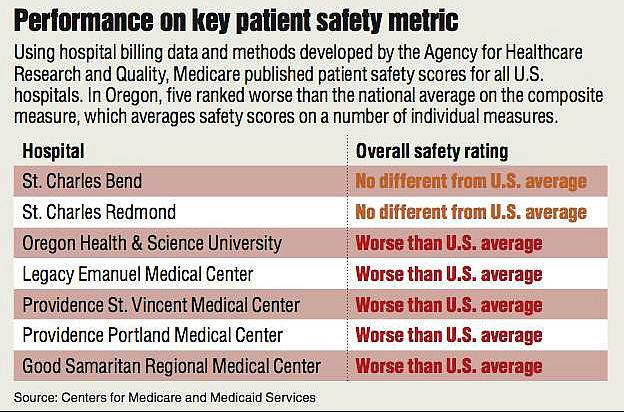

Five Oregon hospitals score worse than the national average on a key measure of patient safety for Medicare patients.

Oregon Health & Science University, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, Providence St. Vincent Medical Center, Providence Portland Medical Center and Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center all have a higher rate of potentially serious complications of care than the national average, according to an analysis released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

All other Oregon hospitals scored within the national average, according to the analysis. None scored better.

“If a hospital has a high rate of (these complications),” said Dr. Patrick Romano, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Davis, “then I think that consumers are entitled to ask some questions about why that is and what the hospital is doing about it and whether that's changing.”

While the analysis included only Medicare patients, a national analysis by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and statewide analysis by the Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research showed a high correlation between patient safety for Medicare patients and for all patients.

The data span patient admissions for 21 months, from October 2008 to June 2010.

The measure, known as the patient safety indicator composite, is meant to give a broad picture of a hospital's quality, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the branch of the federal Department of Health and Human Services that developed it. It calculates an overall rate of serious complications based on how often certain potentially preventable complications occur.

Some of those complications are also reported by CMS individually, as patient safety indicators (see table). The CMS data publication represents the first widespread release of these indicators for individual hospitals.

“I think (the indicators) are very, very useful,” said Helen Burstin, senior vice president for performance measures at the National Quality Forum, a nonprofit organization focused on hospital performance. “It's an important way to understand what hospitals are doing and where they can improve.”

Central Oregon performance

Central Oregon hospitals that were included in the analysis, the 261-bed St. Charles Bend and 48-bed St. Charles Redmond, scored within the national average on the patient safety indicator composite score.

On individual measures of patient safety tracked in the Medicare data, St. Charles Bend was statistically better than the national average at ensuring that its patients were able to breathe on their own after surgery.

The hospital scored within national averages on all other measures. However, when compared with other state hospitals, St. Charles Bend was one of the five worst in the state at avoiding a collapsed lung during surgery. The results, however, were within the national statistical margin of error.

Pam Steinke, vice president for quality and chief nursing executive at St. Charles Health System, the parent company of St. Charles Bend, said the high rate of collapsed lungs seen in the data was not the result of poor practices at the hospital. “I think it's a documentation issue,” she said. “We've looked at (that indicator) several times, and some of the (cases) that got categorized in there were procedures that were done to actually do that, to cause that to happen,” such as draining fluid from a lung, she said.

St. Charles Redmond, however, scored well on this measure, as one of the top five hospitals in the state. The Redmond hospital scored within national averages on all measures reported.

Steinke said she felt good about how the hospital did in the measures and about its overall track record on patient safety. “When we look at the comparisons across the state, the St. Charles hospitals are very favorable,” she said.

Steinke said the hospital and physicians review the patient safety indicators every month to check for potential harm. The indicators, she said, “help us look at specific areas” where the hospital may need to make performance improvements. Sometimes, she said, the issue is one of coding; a procedure was inadvertently coded as a complication. But, when there is a real issue, the staff look to see if it was preventable. “If it was preventable,” she said, staff discuss “what do we need to change to make sure it doesn't happen again.”

Hospital responses

The five hospitals identified by the CMS data had different responses to the analysis.

OHSU, the largest hospital in the state with more than 500 beds, is currently working on a number of “safety issues,” said Dr. Charles Kilo, its chief medical officer. The hospital rebuilt its quality management department about a year ago, he said. “I think we will see improvements in those metrics in the next year or so.”

He also cited some problems with the data, including the extent to which they were risk-adjusted. The data are adjusted to take into account that some patients are sicker, weaker or more prone to complications than others, but Kilo and others say perhaps the statistical manipulations don't go far enough.

A recent analysis by Kaiser Health News and several other news organizations found that major teaching hospitals such as OHSU were more likely to be classified as worse than the national average using the patient safety indicator composite score. In the Kaiser analysis, some experts said this may reflect real problems at those hospitals, or characteristics that could result in problems, such as more residents or fellows going in and out of the hospital.

But others cited in the analysis said academic medical centers may be unfairly singled out. Some said teaching hospitals were more likely to have difficult cases, or perform types of procedures that would result in complications. It may be, too, that academic medical centers are more likely to document such complications, as some hospitals interviewed by Kaiser said.

OHSU is the only Oregon hospital classified as a teaching hospital in that analysis.

Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, a large Portland hospital, also cited limitations in the data. “I think to some extent that (the composite score) is a reflection of complexity of caseloads and patients that is not being adequately addressed in coding and risk adjustment,” said Jodi Joyce, vice president for quality and patient safety for Legacy Health, which is based in Portland and includes six hospitals and multiple clinics.

But Joyce also cited one particular measure, the development of blood clots after surgery, in which Legacy Emanuel was significantly worse than the national average and the worst-performing hospital in the state, according to the CMS data. The hospital had a rate almost twice the national average.

Joyce said that was in fact a performance issue and that the hospital has an initiative under way to address it.

Providence Health & Services, a Northwest health care corporation, issued an emailed statement about its two hospitals that performed poorly, Providence St. Vincent and Providence Portland Medical Center, both large hospitals in Portland.

The statement, passed through a spokesman from Dr. Doug Koekkoek, chief medical officer for Providence in Oregon, also cited irregularities in the data. In particular, he cited the fact that some measures are based on a relatively small sample of cases.

While some measures do include a small number of cases, CMS does not publish those in which the number of cases is too small to be reliably analyzed by statisticians, which is a reason that small hospitals such as Mountain View in Madras and Pioneer Memorial in Prineville are not included. In addition, the composite measure combines the rates for a number of different measures, eliminating the variability that might exist for one particular measure.

At Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center, a midsize hospital in Corvallis, director of quality Vicki Beck said the hospital's below-average score was the consequence of careful documentation and that sometimes complications were inevitable. “The analysis of those kinds of numbers, it counts everything, and sometimes things are just kind of risks of being sick.”

She also said that many of the events counted by the patient safety indicators could be minor. If a surgeon, for example, pierces the wall of a vagina, “that's counted as a tear,” even if the patient isn't harmed. “Did it have patient harm and did it have patient consequence?” said Beck. “Maybe that's a little bit of what's missing here.”

Measuring patient safety

Patient safety is notoriously difficult to evaluate, and the hospitals are not the first to have brought up concerns.

“How do we measure safety?” asked Dr. Niraj Sehgal, associate chair for quality and safety in the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. “The answer is: not very well.”

There are multiple ways to define patient safety and methods to collect data, and “all of them have limitations,” Sehgal said.

For example, the data used in this article are generated using billing claims, which are easier to obtain and process in large numbers but may not always be accurate because of recording errors. Some studies have shown that looking at a patient's medical chart is a better way to detect preventable complications, but much more time-consuming and not practical for analyzing huge numbers of patients.

Still, the CMS data have some very important strengths.

The patient safety indicators were originally developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, a federal government agency charged with improving the quality and effectiveness of health care in the United States.

“They're important measures,” said Burstin, with the National Quality Forum, which has endorsed many of the indicators. “They allow you to look uniformly across all hospitals and see where there are some of these very important safety issues.”

Leslie Ray, a patient safety consultant at the Oregon Patient Safety Commission, agreed that the measures had utility. “I think they help identify and focus on aspects of care that need attention.”

A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that when patients experienced one of the events measured with the patient safety indicators, they tended to incur more costs, had longer lengths of hospital stays and were more likely to die. In some cases mortality rates increased by 20 percent.

Hospital executives interviewed said they, too, felt the measures were important markers of patient safety.

“I really think (the measures) are important to track,” said Dr. David Holloway, chief medical officer for Salem Hospital. “If you look at most of them, these really are things that should never happen in a hospital. ... The correct rate should be zero.”

Salem Hospital had a higher-than-average rate of a collapsed lung caused by surgery or a procedure. Hospital officials were unaware of that distinction, said Holloway, until a Bulletin reporter brought it to their attention.

Holloway said the hospital was going to review cases in which a collapsed lung had occurred to determine whether there were performance issues.

None of the multiple state and national experts contacted for this article said there was one perfect measure for looking at patient safety. Most said they used these patient safety indicators in conjunction with other data on infections, surgical outcomes and mortality rates in developing an overall picture of patient safety.

“They are helpful, but they are not perfect,” said Joyce at Legacy Emanuel. She said the measures “are a great way to establish an overall picture of where there may be strengths and weaknesses.”

Steinke at St. Charles said she thinks the patient safety data can indicate performance issues in a hospital. “You have to look at them in each and every case,” she said. “Our intention is to say, ‘What can we learn from what's there? Is there a trend?' ”

http://www.bendbulletin.com/article/20120309/NEWS0107/203090374/