Portland-area Native Americans take on a diabetes epidemic

By most measures, Native Americans' health problems exceed the average, and it's even worse for urban Indians who can't tap social and health services available on distant reservations.

Today thousands of people from nearly 300 tribes live on this same land. About 2 percent of the metro area's 2 million people identify as Native American or part Native. That amounts to about 30,000 of 102,000 statewide, including nine reservations. Another 9,000 live across the river in Clark County.

This is the second part of an occasional series on health disparities affecting Native Americans in Portland.

Part 1: Portland-area Native Americans burdened by health hurdles generation after generation

Part 2: Portland-area Native Americans take on a diabetes epidemic

Part 3: Native Americans strive for health against alcohol, chaos and trauma

Part 4: A Portland diabetic Native American mother risks difficult pregnancy for fresh start

Part 5: Alaska Native Medical Center a Model for Curbing Costs, Improving Health

In a North Portland health clinic on a dreary Saturday, Michael Teeple does his part in the war against the diabetes epidemic rocking Indian Country.

Teeple, 60, a member of the Ojibwe tribe and diabetic for five years, sees a series of experts at the daylong clinic. Already he's learned his blood sugar and pressure are high. Now he takes his turn with the podiatrist. Dr. Chris Seuferling clips Teeple's toe nails, thick and distorted from a fungus nurtured by diabetes.

Teeple knows the disease can constrict blood flow, which can damage the veins and nerves in his legs and feet -- and lead to ulcers, gangrene, amputation. Blood vessels in the back of his eye could balloon, close off, scar the retina and cause blindness. Thickened and blocked vessels also could destroy his kidneys, and trigger a heart attack or stroke.

"Michael, I expect, will keep his feet for the rest of his life," says Seuferling. "The patients coming in here are not the ones I'm worried about."

The doctor is part of a diabetes care team assembled one a month by the Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest, Inc., or NARA, to help the Indian Health Service take its attack on diabetes to the city.

Native Americans have the highest diabetes rate among all racial and ethnic groups in America and offer a preview of where the rest of the country is headed. They also have found ways to keep the disease at bay.

"The one with the biggest problem has to solve the problem," says Sharon Stanphill, director for the Cow Creek tribal health center in Roseburg. "Indian Country knows diabetes. We know what to do."

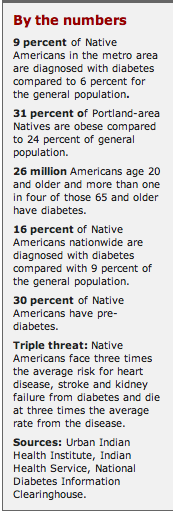

Nationally, one in six Natives have diabetes, more than double that of white Americans. Nearly a third have pre-diabetes. Natives die at three times the rate of the general population from the disease, which can cut a life short by 15 years. Diabetes also steers tribes into a larger share of other health problems.

It is also expensive. Diabetics must daily monitor their blood sugar and most inject insulin. Managing the disease averages $13,240 a year, compared to $2,560 in medical care for a person without it.

Signs of improvement are scarce. The most prevalent form of the disease, Type 2 diabetes, usually strikes adults, though it is emerging earlier, especially among minority youth. Type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes has spread to nearly one in four U.S. teenagers. Equally troubling, the disease progresses faster in youth and is harder to treat.

In the metro area, the epidemic is less apparent, in part because urban Indians like Teeple are less visible, geographically scattered as a small, diverse minority.

And diabetes sneaks up. So Teeple eats a healthy, low-sugar diet, walks regularly, keeps his weight under control and checks in with Ruth Anne McGovern, a family nurse practitioner and diabetes educator at the NARA clinic.

Today, McGovern says a special camera to examine Teeple's retina did not get useful photos because his pupils are too small. He will need to go to another clinic and have his eyes dilated for an exam by a specialist. He has no health insurance.

McGovern tells him he qualifies for a free exam at the Chemawa Indian School in Salem or at the Grande Ronde Health and Wellness Center east of Salem. His third option is an eye clinic in Portland, which could work out a payment plan.

With no car, Teeple chooses the local clinic.  Diabetic dining

Diabetic dining

One morning two months later, Teeple finishes an hour of tai chi and then joins 21 elders upstairs for lunch at NAYA, the Native American Youth & Family Center in Northeast Portland. They often choose foods from the old days -- fish, game, berries, nuts. Teeple loads his plate with rice, salad and buffalo.

In addition to him, three in the group have diabetes, and three are on the cusp.

One is Randy Avart of Vancouver, a Nez Perce retired from the U.S Forest Service. He learned of his diabetes18 years ago. His mother also had it, as did her mother. At 63, he takes insulin injections twice daily along with drugs to lower his blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar.

Also at the table, Mary Renville, a Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, has been diabetic since her late 40s.

"It was a total shock," says the Portland woman, 65. "You feel as healthy as a horse."

The disease runs in her family: two sisters, her mother and brother. One sister died at 43 of kidney failure from diabetes. Her mom died at 58 of heart problems related to it.

Down the hall works Candida King Bird, 38, pregnant and diabetic, whose 85-year-old grandmother in Salem will soon have her second leg amputated because of the disease.

A century ago it would have been hard to find a Native American with diabetes. Today, mostly because of poor diets, alcohol and obesity, they are everywhere. The epidemic is most visible on certain reservations, such as Gila River Pima-Maricopa in Arizona, where half the adults have diabetes, among the highest rates in the world.

"This has been called the thrifty gene," though it's probably a collection of genes designed to ward off starvation, says Hyman, whose recent diabetes book is "The Blood Sugar Solution."

Other experts simply blame poverty. Cheap, processed food typically is loaded with fattening calories. In Multnomah County, a third of Natives live in poverty as do a large majority of single Native mothers and 45 percent of Native children.

Poverty is higher on most reservations, which are also nutrition deserts, Hyman says. Federal food supplied to reservations and to the urban poor also tends to be high-calorie, low nutrition.

"You are lucky if you can find a vegetable within 50 miles," he says.

Poverty also contributes to tribes' high rate of alcoholism. And alcohol fuels diabetes by interfering with insulin, which maintains healthy blood sugar levels.

Long road to health

Nearly seven years sober, Teeple lives plainly in a rented room of a Hayden Island home he shares with two men, both recovering alcoholics. For the last year, he has scratched out a living with day labor, unpacking moving trucks or even taking down a circus tent. Evenings, he watches movies and reads voraciously.

He was born on a reservation on Michigan's Upper Peninsula, soon orphaned and grew up on farms nearby in a series of foster families.

"I have a very strong work ethic, and I attribute it to that upbringing," Teeple says.

The farm also introduced him to alcohol. He remembers his first drink at age 9. During a break from haying, "out came the beer."

One adult said: "Give Mike a drink and see how quick he gets drunk," he recalls.

Teeple was hooked by his first taste.

"After half a can, I was drunk," he says. "I drank to get smashed from that point on."

He graduated from high school, worked in a Ford factory in Detroit and moved to Oakland, Calif. He then settled as a young man in Portland with a good job at Freightliner for 15 years before drinking cost him that job.

"In six hours, I could make $40 to $80," he says. "I drank it all up."

Finally, inspired by a homeless girlfriend, Teeple entered outpatient treatment with NARA. He'd been through treatment before, but this time, sobriety stuck.

NARA eventually moved him into temporary housing. But after years on the street, he found the bed too soft. So he put a pad by the bed and slept there.

"I was just blessed."

Fighting diabetes

Nearly all tribal health clinics have formed teams to track diabetes patients with the $150 million the Indian Health Service spends each year on its Special Diabetes Program.Clinics offer nutrition, weight management, community exercise and diabetes education.

Their efforts are making a difference. In the first decade of the 15-year-old program, patients saw their blood sugar drop 13 percent, bad cholesterol fall 17 percent and kidney dysfunction plummet by a third.

About $3 million of IHS diabetes money reaches Oregon, where it flows to 17 programs, including NARA's.

As elsewhere, Oregon tribal clinics vigorously screen patients 10 and older for high blood sugar, have expanded their diabetes teams and education, and increased drug therapy.

Since 2004, NARA and the Southern Oregon Diabetes Prevention Consortium -- which includes Coquille, Cow Creek Band of Umpqua and Klamath tribes -- also have focused on prevention by changing lifestyles.

They offer pre-diabetic patients 16 classes by doctors, counselors and dietitians on new ways to cook, eat and exercise. Patients get a life coach. They are expected to quit drinking alcohol and to lose 7 percent of their weight. They meet regularly in small groups for a year.

"You can prevent diabetes," says Alison Goerl, the NARA diabetes manager. "A lot of the success is in the relationships we develop with the patients."

The Southern Oregon program has worked with 170 pre-diabetics since it began and less than 5 percent developed diabetes.

That doesn't seem like many given the scope of the problem. But word is getting out and community programs are replicating the Native practices for all Americans, says Sharon Stanphill, Cow Creek health director.

NARA has taken 86 pre-diabetics through its program so far and only four got the disease.

Shirley Stigall, 69, of North Portland, a member of the Wintun tribe, attended the weekly courses two years ago. She continues to write down what she eats and weighs in at NARA once a month. She cooks more and eats more fruits and vegetables since she got her lower dentures. She lost 30 pounds and three inches at her waist.

"I have everything under control," she says. "I'm going to have to take care of myself sooner or later so I might as well do it now."