Safety projects tackle dangerous highway corridors

This is the fourth installment of a special series on highway safety and its impact on Lake County residents' health.

Part 1: Vehicle crash rates among Lake County's chief health issues

Part 2: Alcohol adds a deadly element to area roadways

Part 3: Many agencies contribute to roadway safety projects, planning

Part 4: Safety projects tackle dangerous highway corridors

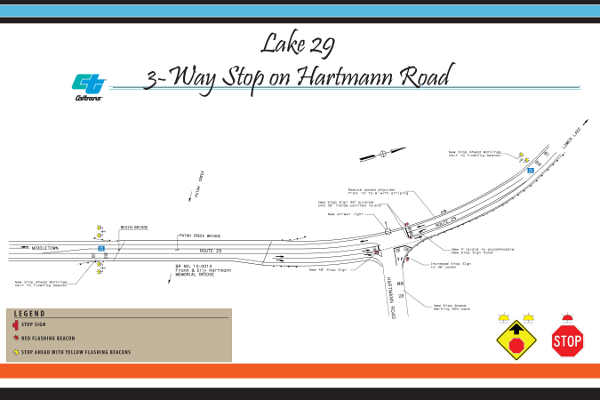

Caltrans workers installed three-way stop signs at the intersection of Hartmann Road and Highway 29 near Middletown, Calif., on Monday, October 24, 2011.

LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – On the evening of July 19, Caltrans officials, California Highway Patrol officers and a Lake County supervisor met with community members in Middletown to discuss what was to be done with a deadly south county intersection.

Hartmann Road – an entry point into the Hidden Valley Lake gated community – intersects with a wide, sweeping curve of Highway 29.

In appearance, it's an unremarkable stretch of roadway. But the statistics that have developed around the intersection led state officials to decide that something had to be done.

A fatal May 2010 crash – which took the life of an elderly couple – already had led Caltrans to conclude that safety improvements would begin there this past June. Improvements initially were to include flashing beacons and additional signage to warn approaching motorists of the intersection.

But on a sunny and clear afternoon on June 23 – just days before those safety improvements were due to begin – 69-year-old Samira Sickels of Clearlake pulled out from Hartmann Road onto Highway 29 and was broadsided by a semi truck.

The crash killed Sickels and seriously injured her passenger, left her family and friends stunned, and resulted in a new appraisal of the intersection.

Hours before the July 19 meeting, Caltrans announced that it would add a three-way stop to the intersection.

Ralph Martinelli, chief of the traffic safety office for Caltrans' District 1, told the group at the Middletown meeting, “We want to stop the carnage that's been going on at that intersection.”

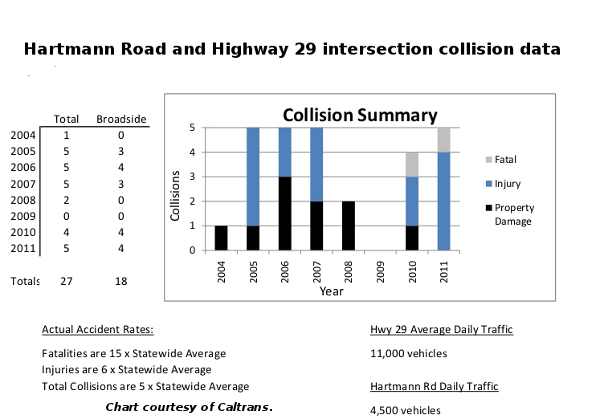

Caltrans' analysis of the intersection revealed that between July 1, 2004, and this past June 30, the 27 collisions had occurred at the intersection. Two of those collisions resulted in fatalities and 13 caused injuries. Eighteen of the crashes were broadsides.

Caltrans concluded that for that seven-year period the Hartmann Road and Highway 29 intersection had a fatal collision rate 15 times the statewide average, while injury collisions occur there at six times the statewide average and the intersection's total collisions are five times the statewide average.

Factors believed to have influenced those collision rates include the south county's population growth and inadequate linkages between county and state roads, according to Martinelli’s statements at the meeting.

Based on US Census data, the concerns about growth have numbers to back them up. From 2000 to 2010, the Middletown area increased from 1,020 to 1,323 residents, a 29.7 percent growth rate, while Hidden Valley Lake’s population increased from 3,777 in 2000 to 5,579 in 2010, a rate of 47.7 percent.

Caltrans crews installed the new stop signs at Hartmann Road and Highway 29 on Monday, Oct. 24.

In an October interview with Lake County News, Martinelli said that as communities grow, full consideration of the consequences for existing infrastructure aren’t always considered. Growth needs to be approached so the proper facilities are in place, he added.

“We have situations where there is significantly increased traffic volumes at some locations,” Martinelli said, adding that the growth may have slowed over the past few years.

Some south county community members have pressed Caltrans to consider a stoplight at the Hartmann Road and Highway 29 intersection, but Martinelli said he doesn’t believe that’s the best approach.

He cited the intersection’s “operational challenges” due to commuter traffic, its orientation – a 1,000-foot radius horizontal curve with a 10-percent cross slope – and the way the road peaks as it crosses Putah Creek, which causes visibility issues.

“We want to stop those high speed broadside collisions that result in serious injury and fatals,” Martinelli said. “The stop signs do that for us.”

Nearby Arabian Road, not currently connected to Hartmann, is believed to be a better eventual location for signalization, said Martinelli.

At the July community meeting, Jim Comstock – who represents the Middletown area on the Lake County Board of Supervisors – said he had advocated for an intersection at Arabian Lane in the 1990s but was overruled, and said he would work with Caltrans to initiate the project.

Analyzing the collisions

Martinelli oversees the Caltrans safety office, which responds to areas that have experienced an increase in collisions. Caltrans receives copies of traffic collision reports from the CHP and uses those to analyze the safety of traffic corridors. However, he said there is usually a lag of nine to 12 months between the time the incident occurs and when it appears in the Caltrans collision database.

Because of that lag, Caltrans works with CHP to stay updated on crashes. “If they see a concentration of collisions they'll bring it to our attention,” Martinelli said of the CHP.

He said all fatal collisions are reported to Caltrans, 70 to 80 percent of injury crashes are reported and only 40 percent of property damage-only collisions make it into the database.

He said the information is assessed quarterly using a statistical tool called a single-tail Poisson distribution to see if stretches of the highway – analyzed in segments two-tenths of a mile long – show crashes to be of statistical significance and above the statewide average.

Similar highway facilities are compared; for example, Martinelli said they wouldn’t compare Highway 175 through Cobb with the four-way freeway that travels through Lakeport. They also look at weather conditions, wrong way crashes, cross median collisions on freeways and the number of cross center line collisions on two-lane highways.

In addition, Caltrans responds to concerns from the community and elected officials, as well as the Caltrans staff who are on the roads every day, Martinelli said.

Caltrans analyzes reports and determines if improvements are required – from trimming trees at an intersection to installing new signs and markers, center line rumble strips and roadway geometric improvements, and stoplights.

Caltrans has two approaches – one that responds to the concentration of collision and conducts a benefit cost analysis to determine what is the best fix, and another that’s not as collision driven but demonstrates a need for road improvements.

When there is a high crash volume at an intersection, Martinelli said they consider seven “warrants,” or criteria, for making improvements.

“The warrants are a tool and a way of evaluating a location so we don't make it worse than it is,” he said, adding that not all seven warrants have to be satisfied to make safety change.

Tackling the problem near Walker Ridge

Another area that gained the attention of Caltrans, CHP and other local officials in recent years was the stretch of Highway 20 near Walker Ridge Road at a spot identified as mile post marker 44.19.

In the nine-month interval preceding the completion of a safety project in that area in October 2009, there were six crashes – one fatal, four causing injuries and one resulting in property damage only, according to Caltrans statistics.

Caltrans’ safety improvements included completion of a pavement replacement project, as well as the installation of rumble strips, reduction of the length of passing lanes and warning arrows on curve exteriors to warn of the sharpness of the curves, according to former CHP Clear Lake area office commander, Lt. Mark Loveless, who left in May to accept a post in Trinity County.

Crediting Caltrans for its efforts at the location, Loveless, said Caltrans “came up with the money immediately” to do pavement resurfacing in the area.

“They took it seriously and they took the extra step,” said Loveless.

Just why that stretch of roadway proved so dangerous is still not clear. “We will never know why,” said Loveless.

He remembered driving the area himself and watching a woman lose control in the curves. “I couldn't figure it out.”

The safety measures, which cost $172,381, appear to have worked. In the nine months after the project was completed, only one collision – property damage only, noninjury – occurred in that area.

Differing approaches to reducing collisions

Other major safety improvements on county highways have shown fatal crash reductions.

In July 2004, Caltrans completed the installation of a new signal at Highland Springs Road between Lakeport and Kelseyville, at a cost of approximately $1,449,539.

In the three years before the signal was installed, there were 13 collisions – one fatal, seven injury and five property damage only, based on Caltrans statistics. In the three years following installation, there also were 13 crashes, but this time there were no fatals. Six of the crashes involved injures and seven resulted in only property damage.

A year after the Highlands Springs light installation was complete, two stop signs and additional lane improvements were installed at the intersection of Highway 20 and Highway 53, with improvements totaling $798,753, according to Caltrans.

In the three years before those improvements were installed, there were 17 crashes at the intersection, located at the base of a hill on Highway 20 and known as “the Y.” Of those crashes, two were fatals, eight resulted in injuries and seven yielded property damage, Caltrans said.

The crash rate went down slightly in the three years after the stop sign installations. In that time, there were 13 crashes, but none were fatal. Five caused injuries and the remaining eight caused only property damage.

Martinelli said the project stopped eastbound traffic and reduced the number of broadside crashes. While he said the number of collisions didn’t drop off completely, the severity of the crashes was reduced, which he said Caltrans considers a success.

A more noticeable improvement was seen at Kit’s Corner, the intersection of Highway 29 and Highway 281, where a new signal’s installation was completed in December 2007, at a cost of $417,400, according to Caltrans.

In the 31 months before the project completion, there were 21 collisions – two fatalities, 11 injuries and eight resulting in property damage only, according to Caltrans. During the same amount of time after the project installation, the collision numbers dropped to three – no fatals, one injury and two property damage crashes.

Martinelli said there are two safety projects on the horizon for Lake County’s Northshore, including a roundabout at Highway 20 and the Nice-Lucerne Cutoff set to start next summer. That will be followed in a few more years by a roundabout at the junction of Highway 20 and Highway 29 in Upper Lake.

“That will be two significant changes at those two locations,” he said.

Roundabouts significantly reduce collisions, Martinelli explained. “There's not the opportunity to have that broadside collision.”

Additionally, the collision rate for roundabouts is about half that of signalized intersections, said Martinelli, with the added benefit of keeping traffic moving. “Operationally they're an advantage.”

While roundabouts aren’t yet common in American driving culture, they aren’t unknown in Lake and Mendocino counties. Within the last decade the city of Lakeport installed one at Todd Road and Lakeport Boulevard, and Caltrans installed one in Hopland and is planning another on Highway 1 near Fort Bragg, Martinelli said.