Sharpening the focus on medical errors

This report was produced as a project for the 2015 California Data Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

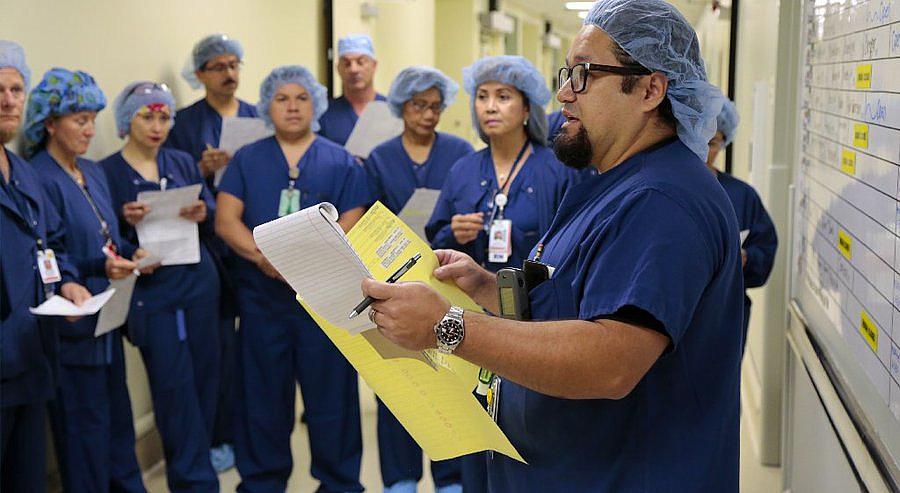

Sam Minero, manager of surgical care at Sharp Memorial Hospital, runs through the daily schedule with the nurses, technicians and other workers who staff the facility's surgical department. — Howard Lipin

SAN DIEGO — At 6:40 a.m. on a recent day, several dozen nurses, doctors, technicians and other workers gathered in the second-floor surgical center at Sharp Memorial Hospital in San Diego for the daily safety huddle.

All wearing scrubs, their heads covered with blue surgical caps, they held copies of the day’s schedule, listening as surgical care manager Sam Minero pointed out the patients whose circumstances called for a little more awareness.

There were patients with latex allergies in rooms one, five and 10.

“Anything we use to care for those patients must be latex free,” Minero reminded, drawing nods from the gathering.

The patient in room nine had a VRE infection. Over in 17, it was methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus.

Half an hour later, across the medical campus in the outpatient pavilion, Dr. Michael Keefe led his surgical team through a quick timeout, repeating his patient’s name and age and the specific procedure to be performed, noting an allergy to penicillin. All of these items and more had already been gone over with the patient and checked upon arrival in the operating room. But hospital policy calls for the surgeon to run through those items one more time before asking for the scalpel. Only after asking each member of the team if they had a question did the surgeon say “we are set to proceed.”

These procedures inside and outside the OR have been in place at Kearny Mesa facility for many years, but Sharp has been working over the last two years to make them more meaningful.

Focus on deepening the hospital’s safety culture tightened in 2012 when a surgical team mistakenly removed patient Paul Kibbett’s healthy left kidney though a cancerous tumor had been discovered on the right. Ultimately both organs were removed, and the patient was forced to rely on dialysis for the rest of his life. In addition to a lawsuit, Sharp received a $100,000 fine and bad publicity, courtesy of the state’s immediate jeopardy system.

The event caused Sharp, the region’s largest health system with four acute-care hospitals in San Diego County, to do some soul searching.

After all, it was not like the hospital was ignoring standard safety procedures. Hospitals across the nation have had an intense focus on error prevention for more than a decade, mandating new fail-safes often adopted from industries such as aviation and nuclear power where one slip-up can cost many lives.

Checklists, which pilots routinely use to make sure they don’t miss critical steps in the complex task of preparing an airplane for flight, have become common in operating rooms. Some, including Sharp, have now begun using wireless electronic tracking systems for surgical sponges that allow surgeons to detect a left-behind item even if it is not visible in a patient’s body cavity.

However, there are still plenty of ways things can go wrong. In the Sharp kidney case, the surgeon decided to move forward without having confirmatory X-rays, taken at another facility, up on the digital screen in the operating room for visualization by the whole team despite the fact that hospital policy clearly stated that X-ray verification is required in cases where there could be left-right confusion.

The incident highlighted a simple truth: Rules and procedures only work if all of the people involved actually follow them every single time.

Safety, then, is just as much about a hospital’s culture as it is about having the right policies, procedures, technology and personnel in place.

When someone decides to skip a step, someone else needs to spot that behavior and call it out.

Dr. Gerald Hickson, immediate past chair of the National Patient Safety Foundation and a quality and safety executive at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., said the true work in increasing hospital safety is changing culture.

“It requires people, process and technology. What has so often happened is, when somebody attempts to put in new procedures like checklists or universal timeouts, surgeon X looks up and says, ‘I’ve been operating for 20 years. I’ve never operated on the wrong side. We don’t have time for this. Move on,’” Hickson said. “That has been, in my view, one of the big factors slowing down the safety movement. Culture trumps everything.”

Sharp seems to agree.

Its latest moves, said hospital medical director Dr. Geoffrey Stiles, have been as much about the way workers collaborate and hold each other accountable as they have been about creating redundant safety policies for high-risk operations.

It has been important, he said, for doctors to understand that a sterling history of safety does not necessarily mean an error-free future.

“One of the big pieces to get them engaged was for them to realize their vulnerability. They were all, for the most part, saying, ‘Yeah, I’m safe, I’m good,’ but, when the American Academy of Orthopedics comes out and says that an orthopedic surgeon has a one-in-four chance of doing a wrong-site surgery sometime in their career, it’s like, ‘OK, I don’t want to be in that 25 percent,’” Stiles said.

Sharp has tried, the director added, to emphasize to its caregivers that reporting errors is a good thing, even creating a “great catch” award complete with a catcher’s mitt trophy and company-wide recognition.

Sharp has also implemented the TeamSTEPPS program created by the U.S. Department of Defense and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which is designed to improve teamwork.

Surgical nursing manager Michele McCluer went through the training and said its emphasis on encouraging all caregivers to speak up if they see a problem is its most valuable feature.

But encouragement, she noted, is actually not the most critical element of success. Employees, she said, need to know that the corner office has their backs.

“Knowing that we will be backed up by our leadership and our management team is very important,” McCluer said.

Changing culture can force some difficult conversations, and no one knows that better than Dr. Tom Karagianes, the soft-spoken medical director of Sharp Memorial’s outpatient surgery pavilion.

He said that, historically, hospital workers have made allowances for disruptive behavior by doctors. That, he said, is a mistake. Though it may be uncomfortable, it is important for management to back its staff by sharing with doctors that the way they talk to their coworkers has real safety implications. It is more likely, for example, that employees will rush through safety checks without paying proper attention if they feel uncomfortable, rushed or anxious.

“A physician who is borderline disruptive throws everybody’s game off,” Karagianes said.

So far Sharp says these changes to culture have had a positive effect. The health care system has not had a “wrong site” surgery since the kidney removal mixup.

Stiles said the new focus on speaking up has occasionally brought disagreements to his attention.

“We have had some that have said, ‘Yeah, yeah, let’s go,’ and we say, ‘No, we have to do the timeout.’ The staff won’t give them the knife. If need be, they’ll escalate it to me or Tom,” Stiles said.

[This story was originally published by The San Diego Union-Tribune.]