Shea finds, then loses, a bed to recuperate

Isabelle Walker provides an in-depth look at Santa Barbara's homeless community in a multi-part series running on Independent.com and HomelessinSB.org.

Part 1: Where do the homeless heal?

Part 2: Santa Clara hospitals give homeless a respite

Part 3: Post hospital stay is whirlwind of beds, programs

Part 4: JWCH gives L.A. hospitals a place to send homeless

Part 5: Shea finds, then loses, a bed to recuperate

Part 6: After ER visit, homeless woman has nightmare weekend

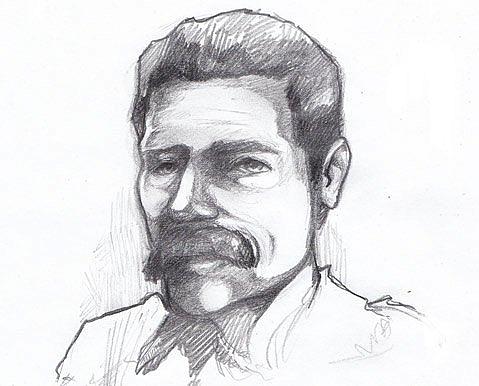

Bill Shea

For two years, Bill Shea lived on the property of Christ the King Episcopal Church. As homeless camps go, it was average. He slept in a field, in a decent bag, and with the blessing of the church's rector. He did not have the long arm of law enforcement to worry about at least. Plus, with a flow of Christians in and out, there was little risk of going hungry. He was surviving — if nothing else.

But then his survival came into question, too. In August, Shea noticed he was winded after even small amounts of exertion. Thinking it would pass, he dismissed it. By mid September, taking just a few steps had become a challenge, so he got some church friends to drive him to Goleta Valley Cottage Hospital (GVCH).

In the hospital, doctors discovered he had atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. He stayed there for six days; when discharge day came, he was released to WillBridge of Santa Barbara.

Unlike William Richardson and Mary Manning, two other homeless people I tracked after they were discharged from Cottage Hospital, Shea¹s discharge was smooth as silk. Discharge planners were in touch with Nick Ferrera, the program manager at WillBridge, a small residence for homeless mentally ill people that also takes in homeless hospital patients. Ferrera knew all about Shea, his illness, and the day he would be released. That day was Tuesday, September 12, and he invited me to come along.

A nurse wheeled Shea through the hospital lobby in a gurney-like contraption, and out to the WillBridge minivan. Ferrara helped him into the back seat. Shea is a heavyset man with blue eyes and a light brown beard; how I might imagine a young Santa Claus to look, in the off season. Shea acted and looked tired, but he was willing to answer the many questions I had for him.

Shea came to Santa Barbara to finish college. He was moving steadily in that direction when his life fell off track. He remained vague about the reasons. He is reported to have had, at some point, an affinity for beer, perhaps even a fixation. Whatever it was that derailed his life, it was never something he could surmount. And then he landed at Christ the King.

As we were driving away from the hospital, Ferrara told Shea that we’d be stopping at the County Public Health Clinic before proceeding to WillBridge, to get the four prescription medications he would now need to take everyday. That process was held up at first by the news that Shea was not registered as a County Clinic patient. Yet, with Ferrara explaining to clinic managers that Shea could not get through the night safely without the medicine his doctors had prescribed for his heart, the three of us were quickly ushered into a side office, where Shea’s personal information was typed into the computer, rendering him officially “registered.”

At WillBridge, Shea was escorted by Ferrara to a small bedroom upstairs that overlooked a busy Santa Barbara thoroughfare. It would be the first night Shea would sleep in a bed (excluding the hospital bed) in over two years.

Ferrara ran down the house rules. No drinking or drugs of any kind; breakfast and lunch are self-serve in the kitchen and somebody named Dawn would stop by later to help with him with his meds. He could sleep as late as he wanted.

When I visited him the next day, Shea was sitting in the small downstairs den, watching television with two other WillBridge residents. His eyes looked heavy. He moved and spoke in slow motion. He said he’d slept well, and described the food as “okay.” He had a doctor’s appointment in the coming week, which WillBridge case managers would drive him to. His medicine made him feel weird, he said.

The following week, Shea’s responses were similar. I caught him smoking on the back patio once.

“I should stop,” he acknowledged.

Shea’s recovery proceeded like this for a month, slowly but steadily. He was given help filling out paperwork for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)---a step towards permanent housing.

Then it all ended. In mid-October, Ferrara said WillBridge’s respite care funding was officially spent. The $20,000 that Cottage Health System (CHS) gave WillBridge to take its homeless patients discharged from the hospital in 2011 was exhausted for the year. Shea would have to move to Casa Esperanza. He would have to finish recuperating in one of their 30 medical beds.

And then he disappeared. Shea simply left the house without telling anyone on a Wednesday afternoon. Because it was locked up, he didn’t take his medication with him, either.

When Ferrara returned from a week off on October 24th, he immediately drove out to Christ The King Church. As expected, Shea had returned to his old stopping grounds and he was happy to see Ferrara, and soon learned that Christ the King was willing to pick up the tab for his respite nights at WillBridge. He could return that afternoon.

So things appeared to be back on track for Shea. He would get the time he needed to heal. He might even get a housing voucher. But less a week after returning to WillBridge, Shea developed an intestinal blockage. Ferrara took him directly to Cottage Hospital’s Emergency Department, where he was operated on.

When I called Shea at Cottage, he gave me the gory details of his surgery and illness and said doctors weren’t predicting a discharge date. But at least now, thanks to his church, he willl have a place to go.