'Silver tsunami' threatens to drown seniors

The growing number of aging baby boomers reaching 60 is putting a strain on California's health care services aimed at helping low-income citizens.

Charlie and Toni Bamer, both 51, would have a serious dilemma if they could not leave his 93-year-old mother, Luz Bamer, at Among Friends Adult Day Health Care Center in Oxnard on weekdays.

Charlie Bamer drops his mother off at the Medi-Cal-funded center at 7:30 a.m. before commuting to Goleta for his job as a maintenance worker. Toni Bamer picks her up at 4 p.m. on the way home from her accounting job in Santa Barbara.

Charlie Bamer drops his mother off at the Medi-Cal-funded center at 7:30 a.m. before commuting to Goleta for his job as a maintenance worker. Toni Bamer picks her up at 4 p.m. on the way home from her accounting job in Santa Barbara.

“If the center closed, either my husband or I would have to quit our job to care for her,” Toni Bamer said.

In Simi Valley, Kathy Ermi, 72, sits at her kitchen table, her legs encased in elastic stockings and propped on a chair. In-Home Supportive Services worker Yenny Chisham, 43, rinses dishes nearby, one of many things Ermi can no longer do for herself since she was diagnosed with cancer, kidney disease and blood platelet deficiency. She also recently had a hip replacement.

The two state-funded healthcare programs that people such as Bamer and Ermi rely on are in danger of being cut or eliminated as lawmakers struggle to pass a 2010-11 California budget that closes a $19.1 billion gap.

Any cuts to the IHSS program would affect about 440,000 low-income seniors and disabled people. Elimination of the ADHC program would affect about 37,000 seniors and their families who would have to find some other way to care for them.

As much of a crisis as this would be, it pales in comparison to the crisis on the horizon, experts say.

It’s what demographers refer to as the “silver tsunami” — the tidal wave of aging baby boomers. As more Californians reach 60, they threaten to swamp an already strained “safety net”— a description of services provided for low income citizens.

“The demographics are going to overwhelm us,” Congress of California Seniors spokesman Gary Passmore said. “The demographic imperative is there, but there has been a denial in California about how to accommodate this population.”

California Department of Aging statistics show this year that one in five Californians — about 6.4 million total — are 60 or older and that we have yet to see the full force of the wave of boomers, many of whom may find themselves in financial straits and in need of a safety net. The 60-plus age group will reach 12.5 million by 2040.

According to the CDA, there will also be a rapid increase in the number of people over 85 — those most likely to need care. Currently, more than 628,000 Californians are 85 and older. By 2040, that number will be 1.7 million.

As each decade passes, the demographic changes will create more pressure on the state budget, according to Hans Johnson, director of research for the Public Policy Institute of California, but there’s one more complicating factor.

“The cost of healthcare has far outpaced the cost of other goods and services,” he said. “It’s not just an aging population, it’s healthcare becoming more and more expensive.”

Lawmakers, scholars and communities are scrambling to find answers.

The IHSS program

This is the second year that Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger has recommended cuts to the In-Home Supportive Services program, which provides state funding for workers who help low-income seniors with basic tasks such as dressing, cleaning, shopping and going to the bathroom.

Schwarzenegger originally called for $750 million to be cut from the IHSS program and asked that the ADHC be eliminated.

“It’s easy to describe them (the cuts) as tragic, but where’s the money coming from? We’re taxed to the hilt,” said John R. Graham, director of Health Care Studies for the Pacific Research Institute, a conservative think tank in San Francisco.

IHSS cuts totalling more than $200 million were approved in the 2009 budget, but a Northern California court has so far prevented the cuts. A two-house budget committee this month proposed a compromise in which they said the state would stop fighting for those cuts in court and repeal them if $250 million in cuts are made in the 2010-11 budget.

The struggle over the 2009 cuts has been keeping lawyers on both sides busy.

“Part of what I have done around the IHSS cuts is try to clean up after disastrous decisions have been made,” said Melinda Bird, senior counsel with Disability Rights California, one of the groups that sued the state to stop the IHSS cuts from going into effect.

H.D. Palmer, the deputy director of external affairs for the California Department of Finance, said he is sympathetic to those who don’t want cuts to this year’s budget, but he believes they are necessary.

“Anything defined as an easy decision is well in the rear-view mirror,” Palmer said. “We understand there are going to be significant impacts if they’re adopted.”

If the cuts to either IHSS or ADHC are made, neither Chisham nor Ermi knows what they will do.

Ermi lives on $1,200 a month in a one-bedroom apartment in government-subsidized housing. She has four children who live in Southern California, but three work and have their own families, and the daughter who checks on her has a degenerative muscular disease.

She believes she would be too much of a burden for any of them to provide her full-time care, and she does not want to go to a nursing home.

“I guess I’ll just sit here and die,” Ermi said.

Chisham visits Ermi about 80 hours a month, coming in on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. She has two other clients. She makes minimum wage, has no pension, no sick days and no paid leave.

The single Simi Valley mother says she also has no idea what to do if budget cuts shrink or eliminate her job. Chisham doesn’t want to go on unemployment.

“You have 200,000 caregivers who could lose their jobs,” Mann said.

The SEIU United Long-Term Care Workers represents about 240,000 of the 409,000 In-Home Supportive Services caregivers statewide. The rest are represented by other unions, depending on the county.

According to the California Department of Social Services, more than 416,000 senior and disabled Californians receive home care from IHSS workers, with 3,764 IHSS recipients in Ventura County. These local recipients get care from 2,580 IHSS caregivers.

“Without the program, they will be forced from their homes and go into institutions, or have nothing and wind up in the emergency room,” said SEIU United Long-Term Care Workers spokesperson Scott Mann.

Some studies, including one conducted by a healthcare and human services policy research company called the Lewin Group, indicate cutting these programs would save money in the short term, but nursing home and emergency room care would ultimately be more costly.

Nursing homes in California cost the state an average of $238 a day, whereas IHSS care costs about $77 a day, according to statistics from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The governor says the problem is that IHSS fraud is “rampant.” According to a release from the governor’s office in July 2009 — the month the 2009-10 budget was signed — several grand jury investigations around California had turned up “egregious” cases of IHSS abuse, including IHSS recipients acting as their own “providers” and pocketing the funds. The governor’s office estimated about 25 percent of all the money going to the IHSS program is going into the wrong pockets due to fraud.

Statistics from the County Welfare Directors Association of California show a much smaller fraud problem. According to its 2007-08 data, of the 24,000 cases of possible IHSS fraud reported in the state, 523 cases were earmarked for further investigation of potential fraud, which is about 2 percent.

John Andersen of Newbury Park believes he should not have to pay for people who failed to prepare for the care of their elders.

“Every dollar I spend in taxes is one dollar less I have to spend on my own family’s care,” Andersen said. “Citizens need to rediscover personal charity and personal responsibility.”

Andersen, a financial adviser, and his siblings have been planning for years for the care of their mother so she needn’t become a ward of the state.

“Too many people have gotten into the mind-set of, ‘Oh, just let the government take care of it,’” he said.

Adult Day Care

The governor’s budget proposal for 2010-11 calls for the elimination of the Medi-Cal ADHC program in hopes of saving $135 million.

Although neither the Assembly nor the Senate has agreed to it, no alternative has been reached and advocates know that a lot can happen in the 11th hour.

“Nothing’s done ’til it’s done,” said Congress of California Seniors spokesman Passmore..

Adult Day Health Care provides skilled nursing, personal care, social services, therapy and nutritional counseling.

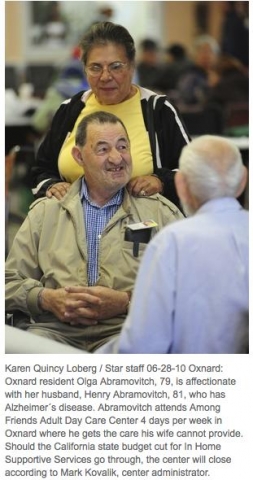

Mark Kovalik, founder and administrator of the Among Friends Center, said he would have to close the doors to the Oxnard facility if funding is eliminated. About 30 percent of the 400 seniors the center serves would probably have to go into a nursing home. He said only 3 percent to 5 percent are able to pay privately.

IHSS workers do not provide medical care, but ADHC workers are trained to medically monitor clients and give some types of therapy.

“I think both programs complement each other,” Kovalik said.

State budget cuts have also affected senior care centers that operate primarily with private grants.

Senior Concerns, a Thousand Oaks senior day care center specializing in Alzheimer’s care, scrambled with fundraising this year to offset the loss of $78,000 in state funding for Alzheimer’s Day Care Resource Centers.

“I had to keep it going. Where else would these people go?” said Senior Concerns facilitator Maureen Symonds.

Pat Hickerson, 82, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2002, and the only socialization she gets and the only break her caregiver daughter gets is on weekdays when Hickerson spends several hours at Senior Concerns.

“When she’s home 24/7, you can’t do anything but pay attention to her,” Sandy Jolley, 63, said. “She’s turned on the stove, I’ve had apples down the toilet. I feel guilty about it, but now and then I need a break.”

Solutions?

Caring for the silver tsunami requires a long-term view, experts say.

One group looking into the way California could better afford and arrange care for the state’s aging population is the Sacramento-based think tank the Little Hoover Commission.

The commission is in the process of coming up with recommendations about the long-term care of elders and the disabled, including in-home supportive services, home- and community-based care, adult day healthcare and assisted-living and nursing facilities.

When it’s finished in about a year, the commission hopes to have solid recommendations on how the state can deliver the right mix of services for the least amount of money. The commission will then present that plan to the governor and the Legislature.

“What prompted this study was the wave of aging Californians — the silver tsunami — and the fact that we have run up against limits about how much the state can afford to do,” said Stuart Drown, executive director of the Little Hoover Commission.

Drown said the report is still in progress, but it’s evident money could be saved by streamlining and consolidating services. The services are scattered, he said, primarily so each program can meet the requirements necessary to get matching county and federal funding.

“We’ve gained an appreciation for the complexity of how to get these things paid for,” Drown said.

The commission is also looking at a program in San Francisco called the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly or PACE model. On Lok’s William L. Gee Center began in the 1970s when the Chinatown-North Beach part of San Francisco tried to meet the needs of elders who had immigrated from Italy, China and the Philippines.

The program provides transportation, medical, social and other types of care that allows people in need of skilled nursing to stay in their homes.

An interdisciplinary team develops an individualized plan for each participant, and members of the community are trained. The PACE program integrates Medicare and long-term care funding to streamline the service, proponents of the plan said.

Graham, of the San Francisco think tank, believes unions have driven up a lot of the cost of the state’s IHSS system.

“You’re throwing money at a unionized pay contract that could be spent more widely on people’s medical needs,” Graham said.

He believes California could benefit from a voucher system, where people would get a certain amount of money from the government to pay for care they choose.

“What we need is a mechanism for people to become less dependent on government and more dependent on their churches, families and fraternal organizations,” Graham said.

Assistant state director of advocacy for AARP, Casey Young, believes the federal healthcare reform bill will help communities as they figure out a model for long-term care in the future, but thinks the ideal model has not yet been developed.

“There are pieces people are working on,” Young said. “I think it’s going to be a number of strategies. The first tenet of it is that people are going to want to stay in their homes as long as they can.”

Passmore believes the answer to the crisis might lie with the very silver tsunami that’s threatening the state’s financial shores.

“We, as baby boomers, are the generation that redefines things,” Passmore, 64, said. “When we showed up in public schools, people didn’t say, ‘oh my gosh, look at all these kids we’d better start cutting pay to teachers.’”

The same ingenuity and political will that has paved the boomers’ way through every passage in life, should be a big advantage as this same population ages, he said.

“We have to figure out for literally millions of Californians, how to age at home with dignity,” he said.

— This article was conceived and produced as a project for The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships, a program of USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Kim Lamb Gregory received a journalism fellowship from the school to explore the question of how potential California budget cuts would affect seniors who rely on the state’s Adult Day Health Care centers and In-Home Supportive Services.