Two Healing Traditions Meet on the Plains

Mainstream medicine finally realizes that they are not alone in the universe. Please visit the Daily Yonder site to see my slide show that accompanies this article. Let me know what you think.

"We have to take this pain from our hearts and really look at it. Leaving it up to our heads only gets us in trouble,"Austin McKay whispered, his gaze still fixed on the vision he had received on Bear Butte, called Mato Paha -- the Center of Everything That Is -- by the Lakota.

McKay's voice was barely audible as he described the experience that removed his terrible fear of being alone and finally allowed him to confront his demons brought on by a life of alcohol abuse. The watery eyes of the Canadian Dakota medicine man remained focused on the revelations from Mato Paha as he spoke, far beyond the walls of the hotel suite in Bismarck with its hot studio lights.

On the edge of my seat, I strained to hear about his troubling dreams that eventually led him to salvation and the responsibility of caring for a pipe, a great honor among the Dakota. Now he works helping others deal with their pain and trauma.

In an attempt to capture his words, the video technicians turned up their recording equipment to its most sensitive levels, so sensitive, in fact, that the producer looked at me in annoyance when I turned the page of my notebook in the back of the room.

I began to wonder if even the most sophisticated technology could capture the power and subtlety of McKay's vision that was so alive it seemed to permeate the room. Could any western technology or worldview, in fact, ever fully describe the gifts of the traditional native healer?

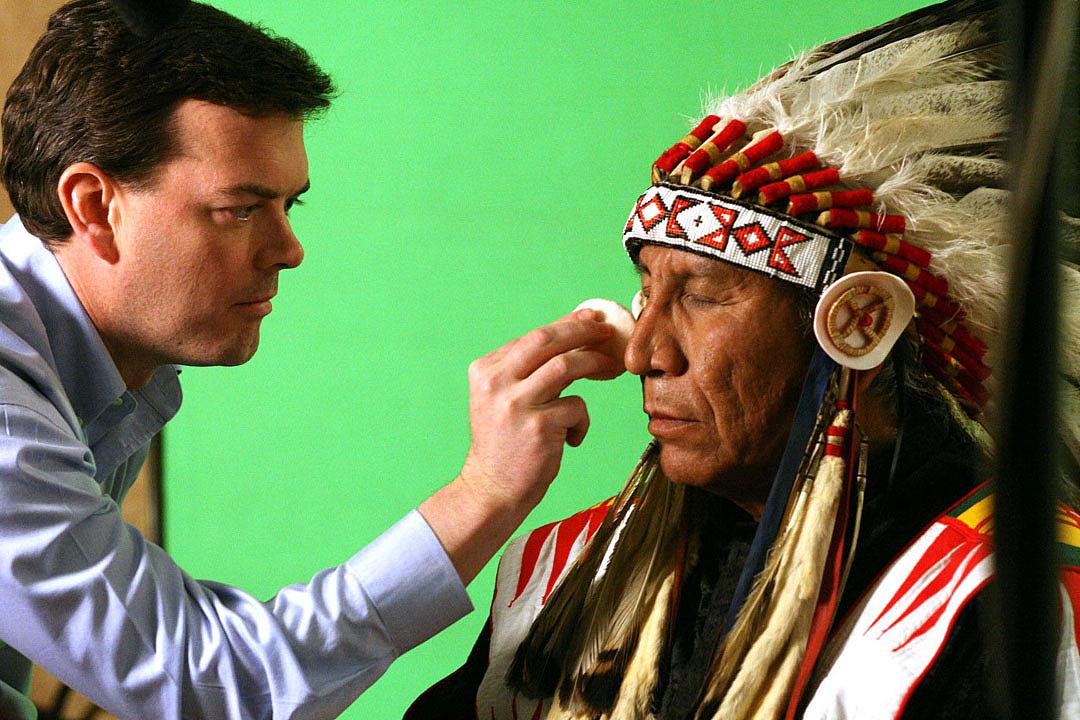

(Left: Chief Leonard Crow Dog, Sicangu Lakota medicine man, spoke about the spiritual dimension of healing. Image by Mary Annette Pember)

The U.S. National Library of Medicine was here to find out. Nine medicine men and leaders had agreed to sit down to talk with the embodiment of Western medicine, Dr. Donald Lindberg, director of the Library located in Bethesda, Maryland. He and his crew were in town in April conducting interviews for the Library's upcoming museum exhibit Native Voices: Native American Concepts of Health and Illness.

Opening in October at the Library's headquarters, the exhibit will feature interviews of 90 traditional healers and leaders from Hawaii, Alaska and the lower 48 states. Over 50 tribes are represented in the exhibit which has been created over a period of six years. The exhibit will also be available at the Library's Online Exhibitions and Digital Project website.

Like those 19th century meetings on the prairie between tribal leaders and representatives from Washington, this promised to be a remarkable event: two sides of the healing coin, traditional and Western medicine, would be facing one another.

As in those old time encounters, the leaders conducted themselves with great gravity. Each had dressed in his finery, a display of rank and accomplishments. Several of the men wore magnificent regalia indicative of their high standing.

For those in the know, the assembly of traditional healers was spectacular. They were (in the order of appearance): Albert Red Bear, Jr. Oglala Lakota, Wajahiah descendent and leader in the Native American Church; Laidman Fox Jr., Mni Wakan Dakota, medicine man and spiritual leader; Tom Cook, Mohawk, spiritual leader and coordinator of Running Strong, a Billy Mills Foundation organization; Austin McKay, Canadian Dakota traditional healer and leader; Chief Leonard Crow Dog, Sicangu Lakota medicine man; Wilmer Mesteth, Oglala Lakota teacher/instructor on traditional plants, philosophy, culture and language; Galen Drapeau, Dakota traditional healer and leader; Rick Two Dogs, Oglala Lakota Wakan Iyeska (Interpreter of the Sacred); and Chief Arvol Looking Horse, Minnecounjou Lakota, 19th generation keeper of the White Buffalo Calf pipe bundle.

Dr. Lindberg also wore regalia for the interviews, his finery being the mantle of the National Library of Medicine, representing the conviction and omnipotence of Western medicine. The 175-year-old Library, located within the campus of the National Institute of Health, is the largest repository of medical research and information in the world. Lindberg has led the library since 1984.

I had anticipated an epistemological smack down at this encounter, but what emerged was far more subtle and revealing.

Lindberg's team of videographers transformed the modest hotel suite into a professional television studio as they filmed interviews with each healer. Although the researchers were sincerely looking to understand and learn from these men, Lindberg's demeanor and dark blue suit said it all; this was his show.

Lindberg's questions revealed the conviction and implied superiority of Western medicine. He asked how the men treated specific diseases and wondered if they went into trances when they conducted healings. The healers demurred at this direct line of questioning and instead spoke of the central role of prayer and humility in their work. They alluded to a power beyond words, the spiritual connection between humans and the earth. "We first ask permission from the Creator to heal people,"said Albert Red Bear.

It began to seem like Lindberg and the healers were speaking in completely different languages. It was hot and close in that hotel room, and I started to wonder where all this was going.

I recalled that Indians have been put under the microscope of Western medicine in countless ways, few of which have benefitted us: the 19th century Smithsonian cranial studies which offered rewards for Indian skulls, the forced sterilization of our women in the 1970s, and the misuse of our DNA in the 21st century, and many more violations of Indian bodies and health.

Western medicine got an old time Indian style bawling out from Chief Leonard Crow Dog who refused to answer questions about what sort of healing was his best work.

"We have everything we need in the universe right here to keep us healthy. Medical science has drugged us. Although we have been treated like handicapped people by the white man, we have survived,"he stated.

"We must be a pretty strong people to have survived so long, right?"he demanded.

"White people are directly responsible for our genocide. Repent! Come clean!

Lindberg appeared chastened and a bit taken aback. Clearly he had not anticipated being taken to task for his race's depredations upon the Indians.

(Right: Cynthia Lindquist, Dakota, president of Cankdeska Cikana Community College (center) brought together Dr. Donald Lindberg, director of the National Medical Library (left) with Albert Red Bear, Jr., and eight other respected medicine men. Image by Mary Annette Pember)

Later, Cynthia Lindquist, Dakota, president of Cankdeska Cikana Community College on the Spirit Lake reservation, explained the implications of the Library's exhibit -- what it could mean for Indian Country. Lindquist is an advisor for the Native Voices exhibit. She stressed that having the director of the U. S. Library of Medicine actively seeking the views of native healers was no small thing. This openness, she said, indicates an important acknowledgement by Western medicine of the native worldview that all life is essentially spiritual therefore healing is deeply connected to prayer.

Lindquist drove over 2400 miles in order to secure the participation of the weekend's nine healers in the NLM's interviews. She personally approached each healer in the appropriate manner as a Dakota woman. Without this humble act, the healers certainly would not have participated.

By brokering such relationships, Lindquist hopes not only that mainstream doctors will gain more appreciation and respect for the native view of health but that native people might gain more trust in Western medicine.

Gradually I realized that the National Library of Medicine folks had their own legacy with which to contend. Theirs was based on an education that sees the body more as a Cartesian-style machine. How could they know, for instance, that Indian people don't usually speak directly about what happens in traditional ceremony? To a mainstream physician such behavior would be labeled as subterfuge.

In our Ojibwe lodge, for instance, we don't describe the details of our ceremonies outside of the actual events. I have been told that to do so would lessen their power. It is the doing and community participation that is of greatest importance. Ceremony is at once a celebration and a recognition and demonstration of our humanness and our inexorable tie to earth.

How is it that a big broad like myself has been able to dance for so many hours in the lodge? I look at the other big old Ojibwe women and we laugh, amazed at ourselves. In ceremony, we are immersed, partnered with the wordless power of life as we dance the sun down, down to the other side of the earth.

The healers spoke of the importance of surrendering human power to the creator and acknowledging that human beings are essentially spiritual creatures forever tied to the spirits of the earth. With this surrender and acknowledgement, they agreed that healing from even the most severe disease is possible.

Albert Red Bear said that healing for ills that plague the Indian community like alcohol, drug abuse and suicide can be found if people learn their indigenous languages and return to their culture.

"When we lose our languages, we lose our souls, our cultures,"said Red Bear. "Relearning our languages can help us sustain ourselves again."

"Our ways were always there waiting for me, waiting for me to turn away from alcohol and take them up, "said Laidman Fox.

In a later interview Lindberg said he had been struck by the impact that loss of culture and language had had upon native peoples.

"That loss of pride has been devastating,"he said.

He was also impressed by the determination of native peoples to survive and reinvent themselves.

This determination to survive and keep culture alive was voiced by all of the healers.

"We don't give up on our patients,"noted Laidman Fox.

Fox and others spoke of cancer patients who had been sent home from hospitals to die, only to be healed in traditional ceremony.

"We put aside the mainstream doctors' prognosis and we start all over again. The support of the family and community helps create the healing,"said Wilmer Mesteth. "It is not my doing."

"And when was your medicine created?"asked Lindberg.

"We have known our traditional medicines and practices as long as we have known Mother Earth,"Red bear answered. "When the U. S. government prohibited these ways, we went underground but we have always been here for the people. We have always been connected; the creator has always been there for us."

"And how long do you spend with your patients,"Lindberg asked.

"As long as it takes, maybe hours, maybe days. We share in their lives and really get to know them,"Fox replied.

"Our healing ways are not based on monetary gain. When people approach us for help. We have to go,"Two Dogs told the library director.

Lindberg expressed admiration and a certain envy for the amount of time that healers spend with their patients. Mainstream physicians, he noted, have a very different relationship with patients.

After the exhausting two-days of interviews, Lindberg seemed subdued but thoughtful.

One of the biggest insights he has gained from speaking with the healers, he said, is that Western medicine isn't very good at treating the root causes of illness.

He also favored the native view that people are responsible for their own health. "This is quite unlike mainstream society in which medicine is expected to 'fix' us,"he noted.

Lindberg was less committal regarding the spiritual element of native healing. I asked him, "Has this experience caused you to question any element of the hegemony of western medicine?"

He answered with a curt, "No,"but added, "Western medicine doesn't understand everything and is subject to correction. We haven't finished learning. We are always open to new treatments."

(Left: Dr. Lindberg, his wife Mary, and the production team greet the nine medicine men who gathered at United Tribes Technical College in Bismark to participate in the National Medical Library's study of traditional healing. Image by Mary Annette Pember)

Increasingly, mainstream clinics and hospitals are allowing healers and medicine men into their facilities to treat patients. Lindberg and his crew visited the Southcentral Foundation in Anchorage where traditional healers are part of the paid staff of health care providers. Managed by Alaskan Natives rather than federal authorities, the Foundation has named their system, Nuka, an Alaskan Native word for "strong."

"IHS, (Indian Health Service) allows and encourages traditional healers to come in for patients who request that help,"observed Mesteth.

"In the past, the government tried to stifle our culture,"he added.

There is an increased interest from mainstream medicine and U.S. society as a whole in traditional healing and medicine, Cynthia Lindquist observed. She noted the many medical studies about the power of prayer in healing. In 2006, the New York Times reported that at least 10 studies about the impact of prayer on disease had been conducted in the previous six years.

"The essence of native spirituality is the belief that everything on earth has life and value. Prayer is a means to acknowledge that value and acknowledge a power greater than ourselves. We have always known this,"said Lindquist.

In the past, she noted, the U.S. government and society condemned Indian people for their beliefs.

"Our prophecies told us that they (mainstream society) would come to us for answers,"she noted.

Galen Drapeau observed, "In today's society, we don't take time to tend to our minds, hearts of spirits."

The healers agreed that people are suffering due to this negligence of themselves and the earth.

"Polluting our water and land insults the gifts given to us by the creator,"said Red Bear. But he also spoke of hope. "We have a second chance. The land is still here and our culture is alive!

In October, a special Healing Pole will stand at the door of the Native Voices exhibit in Bethesda. The Library commissioned Jewel James, an artist of the Lummi Nation in Bellingham, Washington, to create the massive carving which tells a symbolic story of the intangible power of prayer. It will be a reminder of Chief Crow Dog's words that the sacred way of life is the most important and his instructions for a good life:

"You must see with the eye of the heart of your mind."