Viewpoints: Out of struggle, a new direction

The struggles with trauma are common among Vietnamese refugees and immigrants who suffered postwar persecutions in Vietnam. People living with depression and anger can hurt themselves and their families. Yet because of cultural stigma associated with mental illness, those affected are uncomfortable seeking medical care.

For months, Thuy Thanh Nguyen could not sleep. The refugee from the Vietnam War and a communist gulag would cry for hours, snap at her husband and children, and throw things at them.

For months, Thuy Thanh Nguyen could not sleep. The refugee from the Vietnam War and a communist gulag would cry for hours, snap at her husband and children, and throw things at them.

She attempted suicide twice, and failed. The first time, she locked the family catering store but forgot to remove the "Open" sign. A customer knocked on the door when she was opening a bottle of poison. The second time, she closed the store, but the Vietnamese businessman next door came over and insisted, "Sister, please make me a meal." She couldn't turn him away.

She went to several psychiatrists, but the monthly 20-minute sessions were not helpful. She was sent to the Orange County's Behavioral Health Department, but heard that if she were diagnosed with a mental illness, she would not be allowed to see her children. She dodged the doctor's order.

That was back in 2002, a year after she lost her eldest daughter to a brain tumor. Nguyen had devoted all of her energy for the previous year to care for her daughter, 31-year-old Thao Thuy Le, through a series of surgeries.

Afterward, Nguyen was diagnosed with cervical cancer, which Vietnamese women are five times more likely to get than women of other ethnicities. She had two operations, and survived.

During her cancer treatment, Nguyen had to give up the catering business, which her family had worked diligently to build. She lost control of everything she had worked hard for: her daughter's health and survival, her family's business, her sense of self-reliance.

"The past trauma kept appearing as if a film on the TV screen, playing and rewinding," Nguyen recalled. "The 13 years in the gulag haunted me day and night. I could not push it away. I was in severe pain."

The struggles with trauma, like Nguyen's, are common among Vietnamese refugees and immigrants who suffered postwar persecutions in Vietnam. People living with depression and anger can hurt themselves and their families. Yet because of cultural stigma associated with mental illness, those affected are uncomfortable seeking medical care.

However, that is changing. Tri Nguyen, a mental health practitioner at the Community Research Foundation in San Diego, said, "Although we are still far behind the mainstream population in understanding and accepting mental illness as a medical problem, I do see an increase in the acceptance and motivation to seek mental health services in the Vietnamese/Asian American communities in recent years."

In 2003, Nguyen's 29-year-old son, Quan Long Le, repeatedly urged her to seek help. She refused. Eventually he called Orange County's help line. A Vietnamese-American social worker answered.

Over a five-year period, the social worker helped Nguyen overcome some of her depression and fears. But she is still afraid of some noises and is unable to drive. The jangling of keys – a signal of intense interrogations in the gulag – causes her to go berserk.

Nguyen's acceptance of treatment and her progress broke a silent wall that had stood as a barrier to Vietnamese Americans with PTSD. "I refer several of my friends to this service, and they lead a much happier life now," Nguyen said.

Her story resonates with many others, from mothers with disabled children, to veterans affected by wars, to women surviving cancer.

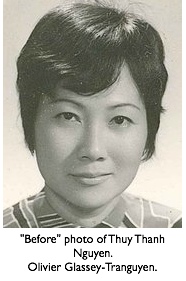

When Thuy Thanh Nguyen and her family arrived in California through the Humanitarian Operation program in 1992, she brought with her some prized possessions: two pairs of frayed gloves, which she had sewn and worn while imprisoned for 13 years after the Vietnam War ended, and two sweaters stamped with her labor camp identification numbers – one of which she had made herself, using her daughters' old sweaters.

She also brought with her intangible possessions – an unyielding determination, a sense of service to humanity, a strong faith in God, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Following the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, homes of South Vietnamese were confiscated, public facilities taken over, socio-cultural groups banned, schools disrupted, and civilians imprisoned.

Nguyen, a member of the Republic of (South) Vietnam Police Federation, and her husband, Long Thanh Le, a military academy graduate and member of the army, along with professionals, educators, intellectuals, writers, artists, landowners and entrepreneurs, were persecuted and forced into the gulags.

Nguyen was sent to a male prison and was hounded around the clock about her police career in Saigon. After months of interrogation, the communist government sent her to a labor camp.

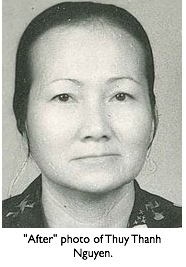

In 1981, she faced solitary confinement in a windowless cell. She was chained and interrogated for long hours, received only water and a ball of rice each day, and slept on a concrete floor. Nguyen became jaundiced and paralyzed, and contracted malaria.

But the thought of reuniting with her children kept her going. She always called out to God, trusting that God would help her through the times when she witnessed fellow inmates die from exhaustion, starvation and sickness. After 13 years, Nguyen was released because of her failing health.

When she was reunited with her family in Saigon, her looks frightened her children. "Mommy looks scary without teeth!" she recalled them saying.

The government continued to persecute Nguyen and her family until the Humanitarian Operation helped them relocate to the United States. Leaving Vietnam was a difficult blessing. Nguyen left behind her aging mother, the pillar of her family during the horrendous time in the gulag.

In March, state Sen. Lou Correa honored Nguyen as a "Woman Making a Difference" for her "commitment, dedication, and enthusiasm in serving the Orange County community" where she volunteers with the Republic of Vietnam Disabled Veterans and Widows Relief Association and other groups associated with Republic of Vietnam veterans.

Nguyen's life is mirrored by the Vietnamese commemoration of Black April – the fall of South Vietnam – and that of a bright April – a new direction for those who seek to rise from the darkness of war. Her story of trauma and loss, her community service and spirit of survival, and her journey toward healing can help other Vietnamese Americans and their fellow countrymen connect and heal.

Trangdai Glassey-Tranguyen's reporting on emotional health in the Vietnamese diasporas was undertaken as part of the California Endowment health journalism fellowships, a program of the University of Southern California's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Visit her blog at www.reportingonhealth.org/users/trangdai-0 and reach her at vietnamproj@gmail.com.