Everybody Hurts: Powerful Prescription Database Languishes

Just three years after California Attorney General Jerry Brown – now the governor – announced a newly improved prescription drug tracking system while standing beside a dad who lost his children as a result of prescription drug abuse, that system is all but useless.

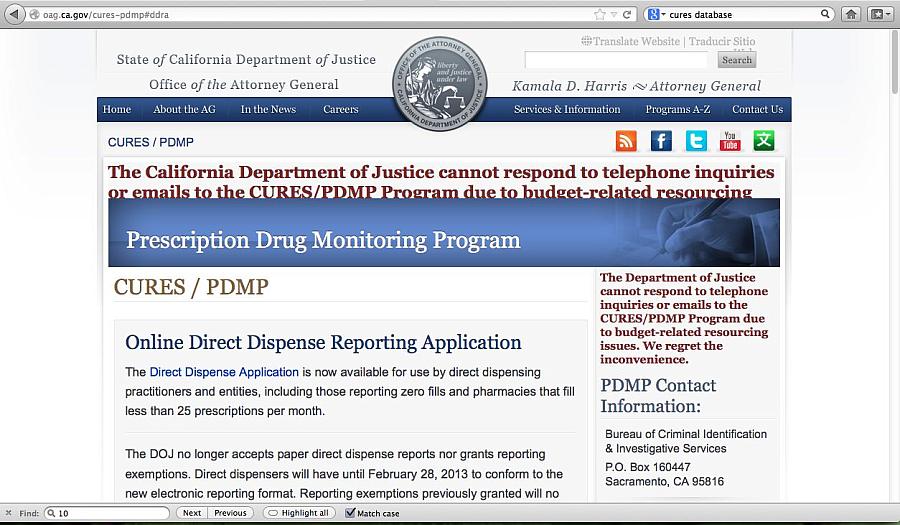

The first thing you see when you go to the CURES website is this message: The California Department of Justice cannot respond to telephone inquiries or emails to the CURES/PDMP Program due to budget-related resourcing issues. We regret the inconvenience.

CURES stands for Controlled Substance Utilization, Review and Evaluation System. The system was supposed to work in real-time. No email. No faxes. Just log on to the website and plug in a patient’s information to find out how frequently they had been getting prescriptions for painkillers and other drugs. It was supposed to stop the kind of reckless behavior – on the part of patients and physicians – that led to the deaths of 10-year-old Troy Pack and his 7-year-old sister Alana. They were killed when a nanny who had been gobbling up painkillers ran them over in Danville, California.

The system had been around for years but it had failed to catch the nanny, Jimena Barreto. So the children’s father, Bob Pack, helped re-engineer the system after their deaths. And Brown invited him to a press conference to tell the world that the state would no longer waste time in how it tracked prescription drug abuse. Scott Glover and Lisa Girion at the Los Angeles Times wrote:

Brown announced the start of real-time access to CURES at a news conference in September 2009. Pack was at Brown's side as he touted the "high-tech monitoring system" that would "enable doctors and law enforcement to identify and stop prescription-drug seekers from doctor-shopping and abusing prescription drugs." … Law enforcement officials and medical regulators could mine the data for a different purpose: To draw a bead on rogue doctors.

Here’s what that would look like. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency has a similar system that mines the same data. If a doctor racks up too many prescriptions in a year, the agency can start to investigate. Readers of my Shadow Practice series may remember that after learning about massive orders of painkillers for one clinic in Orange County, the DEA started targeting Dr. Harrell Robinson. Eventually, the agency took away his ability to prescribe pain meds.

This is not to say that the DEA is handling prescription drug abuse perfectly. But, at least, it recognizes that it makes sense to pay attention to big prescribers. California’s CURES holds the promise of real-time tracking of reckless prescribers, too. But CURES isn’t going to catch any Harrell Robinsons anytime soon.

Despite Bob Pack’s best intentions, the system ultimately was set up to track patients, not physicians. It can be used to create lists of the state’s top prescribers for a range of drugs, but the state doesn’t actually do anything about those top prescribers, even when it is obvious that their prescribing patterns are far outside the norm.

CURES won’t catch any Jimena Barretos any time soon, either. Barreto was the woman convicted of murder in the deaths of Troy and Alana. Glover and Girion wrote:

CURES is now run by a single full-time employee in the attorney general's office. A private company under contract with the state collects electronic reports on prescriptions from pharmacies and enters them into the database. The effort is funded with about $400,000 in fees collected annually from the medical board and other professional licensing agencies. Of more than 212,000 physicians, pharmacists and other professionals eligible for online access to CURES, fewer than 10% have signed up. The attorney general's office says the database could not handle the demand if every eligible prescriber signed up for online access.

Have you heard this one before? The government can’t enforce the law or meet its objectives because it doesn’t have enough money. I don’t know if I’ve written a story that involved a government agency where that complaint wasn’t raised.

Let’s assume it’s true. (You may beg to differ.) I’ll write more about how much money would be enough in my next post.