Measles mania puts spotlight on vaccine exemptions. And Mississippi?

Measles is back.

The recent measles outbreak that started at Disneyland reminded us yet again of that which we already knew about infectious diseases: It’s a small world, after all. Since late December, talk of measles has seemingly saturated every newspaper, radio broadcast and evening newscast in the country. The usual measles media trickle has become a flash-flood torrent.

The great bulk of daily coverage keeps tabs on climbing case numbers and the steps being taken by local and federal health officials to contain measles’ further spread. But one of the salutary side effects of this growing story has been the focus it has placed on the controversial practice of vaccine exemptions.

And where parents’ personal choices suddenly become reframed as questions of public health safety, local stories turn national. From Marin County, an anti-vaccine stronghold, we heard the story of a worried father pushing for his son’s Tiburon elementary school to bar unvaccinated kids, because his son – in remission from leukemia – is unable to receive the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine and could fall very ill. We also heard about an Arizona pediatrician, Dr. Tim Jacks, whose 10-month-old son is showing signs of measles after visiting a Phoenix clinic that treated another patient who was infected by a Disneyland visitor. Jacks’ 3-year-old daughter has an immune system weakened from chemotherapy, and he fears for her.

“Your poor choices don't just affect your child,” Jacks wrote in a blog post signed “Papa Bear.” “They affect my family and many more like us. Please forgive my sarcasm. I am upset and just a little bit scared.”

These are compelling stories because they show the fear and anxiety of parents on the other side of the vaccine debate — the parents of vulnerable children who fear for their kids’ lives because other parents have decided, for reasons of faith or philosophy, not to vaccinate. One parent’s freedom to choose is another parent’s anxious nightmare.

That doesn’t mean this conflict plays out the same way everywhere. Perhaps the most fascinating piece of reporting to come out the measles crisis so far is a story last week from Todd C. Frankel of The Washington Post. Even the story’s own headline can scarcely believe what it’s saying: “Mississippi – yes, Mississippi – has the nation’s best child vaccination rate. Here’s why.”

Mississippi doesn’t have a measles problem, Frankel explains, because nearly all of its children receive the MMR vaccine:

Mississippi has the highest vaccination rate for school-age children. It’s not even close. Last year, 99.7 percent of the state’s kindergartners were fully vaccinated. Just 140 students in Mississippi entered school without all of their required shots.

In California, epicenter of the measles outbreak, about 8 percent of kindergarteners didn’t get the MMR vaccine, while Pennsylvania’s rate is around 15 percent. While many states allow parents to obtain “personal belief exemptions,” Mississippi (and West Virginia) only allow medical exemptions — and even those are rare. Frankel explains:

The secret of Mississippi’s success stems from a strong public health program and — most importantly — a strict mandatory vaccination law that lacks the loopholes found in almost every other state.

The story distills the state’s approach to child vaccinations into a single memorable line: “In the Magnolia State, public health trumps parental choice.”

That is obviously not what you’d expect in the Deep South, where government intrusion on individual liberty is a perennial political talking point, nor is it what you’d expect from a state that routinely ranks at or near the bottom on health indicators such as obesity and infant mortality.

But Frankel’s frame on the measles outbreak goes beyond Slate-style contrarianism. The story reminds us that health stories — even those about highly infectious diseases — are rarely just about health. They’re also stories about politics and how we collectively balance the individual right to choose, on the one hand, and public health imperatives, on the other. Political abstractions become more concrete for parents anxiously checking their chronically ill child’s forehead for fever.

The debate over vaccines will continue, but the alternatives are clearer. Mississippi offers one answer, California another. They just happen to be opposite from the answers you’d expect.

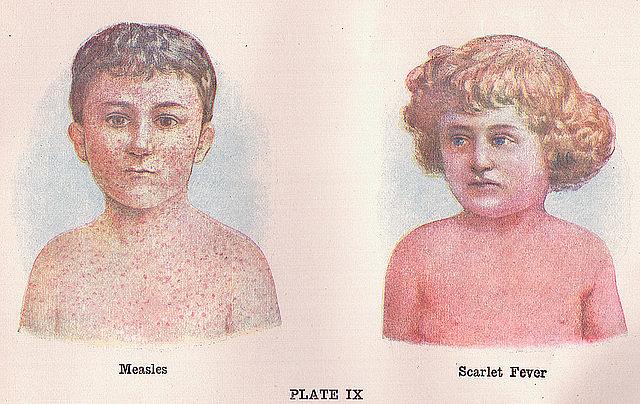

Illustration: Sue Clark via Flickr.

Related posts