Your mother may not love you, and other anecdotes about a beloved professor

Last week, I found out my favorite journalism professor had passed away. I used to call him now and then, but hadn't in several years. By all accounts, he lived a good life; he died last year surrounded by friends at 85.

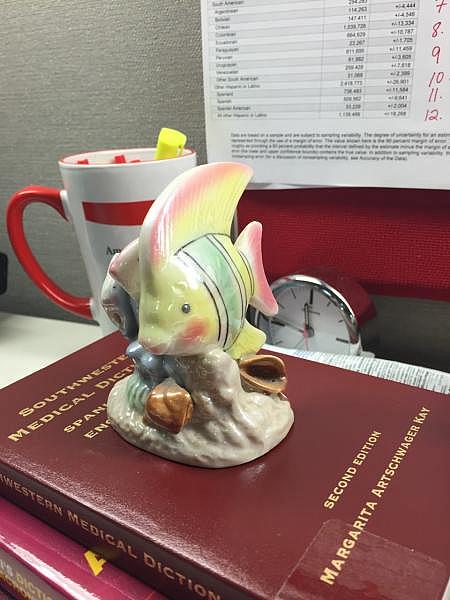

The kitschy ceramic sculpture in the photograph below was a prize I won twenty years ago in his introduction to reporting class for writing the best lede for an assignment. It is one of my cherished possessions, a reminder that reporting was what I was meant to do.

Alan Prince was a newsman through and through. A reporter's editor and a tough one. For one of his most memorable assignments, we had to interview someone who had HIV or AIDS and find out what they had planned for their funeral. One of my classmates and I rode the train to Miami's Jackson Memorial Hospital and met a guy who was a great profile. I then called him and asked whether she and I could co-write it, and he replied, "Sure. And if you get an A, I'll split the grade in two and you'll each get a C."

In his obituaries, family and friends remembered him as a charming, generous and witty man who was a talented magician. One of the tributes said he'd always wanted a career in journalism. Students remembered him as a demanding and wonderful professor whose lessons have stayed with them more than twenty-five years after taking his courses.

In his long and successful career, Alan Prince was a reporter and editor at the Miami Herald, where he worked twenty-five years. He also taught at the University of Miami, where I was a student, and at Florida Atlantic University.

One of his singular traits was that he had an inherent distrust of authority and encouraged us to do the same. Among the lessons that have stuck with me: Always attribute what sources say, don't trust them because they may be wrong or they may lie. He told us not to believe even our mothers when they told us they loved us. He used to say something along the lines of, "Your mother says she loves you, but you don't know that's true."

There were grammatical lessons, too. I've never fogotten how to spell "nickel," the differences between "to lay" and "to lie," and "to convince" and "to persuade."

This was a man who was hard-core old school about reporting and was not above yelling at you when you did someting stupid. He was a passionate professor who made you want to do good work. If you polled students who took his class, they'd tell you they hated him or they loved him. I was in the latter camp, and I know, as I knew then, I am the better for being in his classes. In the end, a handful of us earned the privilege of calling him Alan.

Alan Prince lived and breathed the history of American journalism. He made us memorize the First Amendment, and would give us pop quizzes for which we had to write it out. During the course, there were a few people whose names he wrote in such large handwriting on the blackboard they took up the entire space. They were his heroes. One of them was John Peter Zenger, a German immigrant who in the 1730s became one of the first American newspaper publishers and journalists tried for libel. Another was Elijah Parish Lovejoy, an abolitionist journalist and editor killed in the 1830s by a mob who set fire to one of his printing presses.

Here's to Alan Prince, and the many other professors like him who have inspired us to be journalists, to do the good, messy and hard work of reporting and writing the news.