Candidates fail to grasp how Canada’s health system really works

Please stand if you're not clear on the details of Canada's health insurance system.

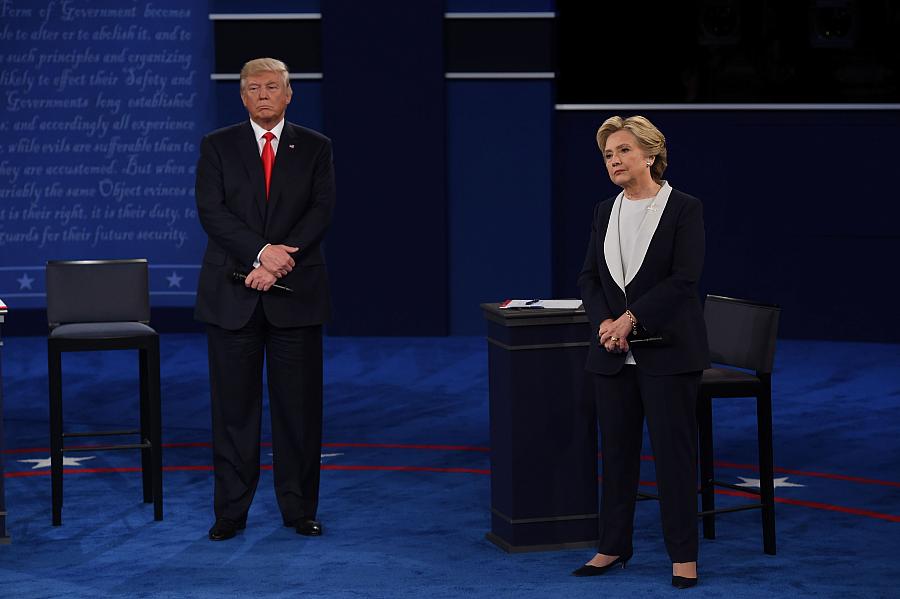

Here we go again. This time it’s Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s turn to demonize the Canadian health care system. During Sunday’s debate Trump accused Clinton of supporting a single-payer plan, “which would be a disaster, somewhat similar to Canada,” he said. “And if you hadn’t noticed the Canadians, when they need a big operation, when something happens, they come into the United States in many cases because the system is so slow. It’s catastrophic in certain ways.” As for Clinton, the batch of WikiLeaks released last Friday reveal that in one speech she said, “If you look at the single payer systems, like Scandinavia, Canada, and elsewhere, they can get costs down. But they do impose things like waiting times, you know” — a sly way of making it appear there’s trouble north of the border.

Ever since I’ve been covering health policy, the pols and the media have been disparaging Canadian and European health care. Back in 1991 a New York Times editorial pounced on waiting lists for Pap smears, which brought a strong rebuke from the Canadian ambassador who sent a letter to the Times: “You, and Americans generally, are free to decide whatever health care system to choose, avoid or adapt, but the choice is not assisted by opinions unrelated to fact.” The facts in this case were that there had been a delay several years earlier in Newfoundland, but had since been cleared up. “Elsewhere in Canada, Pap smears continue to be done immediately upon request, as has always been the case,” the ambassador wrote.

During his brief presidential run in 2007, Rudy Giuliani announced his chances of surviving his prostate cancer were 82 percent in the U.S. but only 44 percent under England’s “socialized medicine,” a claim later debunked. And more recently during Senate debate on the Affordable Care Act, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell opined: “Americans don’t want their health care denied or delayed. But once government health care is the only option, bureaucratic hassles, endless hours stuck on hold waiting for a government service rep, restrictions on care, and rationing are sure to follow.”

Restrictions on care? Rationing? This is scary-sounding language whose purpose is to thwart any serious political discussion of a national health insurance system.

This latest round of dumping on Canadian health care calls for fuller discussion, one that moves beyond scare talk. In reporting about a nation’s health care system, there’s nothing black or white, and that includes our own.

In the early 1990s, conservative interests in Canada were sending messages that patients in western Canada were being denied life-saving heart surgeries and flocking across the border. At the time I interviewed a Vancouver judge who headed a Royal Commission looking into that claim. Each of those cases fell apart, he told me. If patients went to the U.S., it was for reasons other than long wait times — a wait for a particular surgeon, for example, or because they had family in the states.

Three years ago I spent a month in Canada as a Fulbright Senior Specialist examining that country’s health care arrangements. My takeaway: Americans don’t know much about how Canada’s system works, and Canadians don’t know much about ours. Too many Americans believe Canadians are dying on the streets for lack of care; too many Canadians think Obamacare is a national health system like theirs. “After all that, you will still have 30 million people without coverage?” a former deputy health minister in New Brunswick asked me.

Canadian health care is hardly the disaster Donald Trump and other pols have claimed. It is far more equitable than the American system. Because it’s publicly funded through the tax system, everyone has insurance and pays no coinsurance, copayments, or other fees at the point of service. There are no shiny gold plans for wealthier people who can buy better coverage or lowly bronze plans for those who can’t. When I have lectured in Canada on the American system, I’m always asked, “What are copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles?” To Canadians, those words are as foreign as Swahili.

Their system costs less. Doctors are paid fees for their services, which are negotiated through a contentious bargaining process with the provincial governments. As in most national health systems, the power of the government to push against the persistent demands of providers for more money keeps overall medical costs much lower than in the U.S. In 1970, before Canada adopted its current system, both countries spent roughly 7 percent of their GDP on health care. Four decades later, the U.S. spent about 17 percent, Canada 10 percent.

Through global budgets for hospitals and some controls over expensive technologies — waits for MRIs for minor sports injuries — Canada has managed to keep costs more or less under control. However, high drug prices, unequal drug benefits, and the lack of a pharmaceutical benefit for about 10 percent of the population are big issues.

And what about every politician’s poster child for Canada’s health care ills — the infamous waiting lists? Here, too, the picture is more complicated. In its rebuttal to Trump, Vox reached back to a 14-year-old study in Health Affairs that “found no evidence for the idea that Canadians are fleeing their health system, and concluded it’s a ‘persistent myth.’” Indeed it is! In the early 1990s, conservative interests in Canada were sending messages that patients in western Canada were being denied life-saving heart surgeries and flocking across the border. At the time I interviewed a Vancouver judge who headed a Royal Commission looking into that claim. Each of those cases fell apart, he told me. If patients went to the U.S., it was for reasons other than long wait times — a wait for a particular surgeon, for example, or because they had family in the states.

This not to say there aren’t waits for some services at some times in some areas, and yes, some Canadians do get annoyed, especially those who may have to wait for joint replacements. But most aren’t coming here to get treatment for non-emergency care. For one thing, it costs too much.

To discuss all this, I rang up Dr. Robert McMurtry, a prominent orthopedic surgeon who has held many important posts and has chaired the Wait Times and Accessibility Work Group for the Health Council of Canada, since disbanded. “There’s no question if you need it, you can get rapid care,” McMurtry told me. “What still goes on is excellent urgent and emergent care.” He added, “the publicly funded health care system remains tremendously popular, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t all sorts of things we can do about wait times, and we’re not.”

McMurtry explained that often people are on waiting lists who should not be on them, and that better, centralized management of the lists would be a step forward. He said that the lists needed to be periodically validated and monitored to make sure that patients did not fall between the cracks. Right now, he said, some individual doctors maintain their own lists and that practice leads to gaps in service. One successful program for reducing waits for orthopedic procedures in Alberta ran into the “permanent bureaucracy” when attempts were made to implement it more broadly to other conditions. “It would take political will at the most senior levels,” McMurtry said. “There’s a gap between what we’re doing and what we could be doing.”

It seems bureaucratic obstacles can be impediments to improving care no matter what a country’s insurance arrangements are. But both the U.S. and Canada rank at the bottom of The Commonwealth Fund’s list of international comparisons of 11 countries based on a number of metrics, including quality of care, access, efficiency, equity, and expenditures.

Each time some politician talks about Canadian or European health care, the dreaded “R” word comes up; the suggestion is that other countries ration care and the U.S. does not. No health care system can afford to provide every service to every patient when they demand it. Every country has a way of distributing services. The U.S. rations by price rather than waiting lists. If you can’t afford care, you may not get it. Think of the millions of people with incomes below the poverty line in the 19 states that have not expanded Medicaid. Or the Nebraska woman I noted in my post last week who complained about sky-high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs. “We are pretty much healthy people and with our high deductible I can hardly make myself go to the doctor (for allergy shots) because it runs me about $300 when I do.” Or consider a person who needs brain surgery but his insurer’s narrow provider network prevents him from choosing the best surgeon because she charges more and is not in the network.

One day in Canada I was asking questions of customers in a Toronto coffee bar. One employee taking orders was about to go off duty and sat down to talk. “I’m tired of hearing you Americans talk about rationing in Canada,” he said. “Let me tell you how many MRIs I had when I was riding my bike and got hit by a motorcyclist.” He had been hurt and received an MRI in the emergency room and a couple more during his brief hospital stay. He said doctors wanted to make sure he was OK before releasing him. The barista got well and left the hospital without a humongous bill for his care.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is Contributing Editor of the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care blog.

(Photo: Robyn Beck /Getty Images)