Mental Mapping: Research reveals simplicity of brain patterns

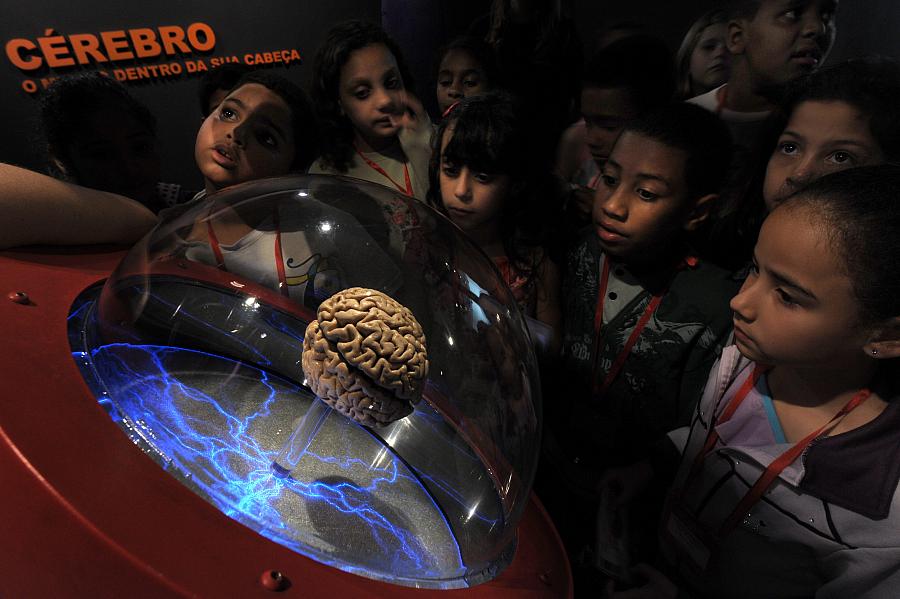

Photo by Mauricio Lima/Getty Images

Brains are simpler than you think.

That’s not the line you usually hear. When I meet someone in medicine — especially someone on the mental health side — I often say something along the lines of what I said in my last post. Why don’t we have a better toolkit for the brain, the way we do, say, for the heart? The number one response is this: the heart is just a muscle. The brain is so much more complicated that it’s harder to fix it when something goes wrong.

“The human brain is the most complex system we know of,” says Hermann Haken, the renowned German physicist.

When I hear something like that I usually change the subject to the latest Truckfighters album or that book by Christopher Farnsworth.

Now I have a better comeback. As part of the Allen Institute for Brain Science’s Brain Atlas project, researchers examined six different human brains — donated after death — including: three “males of European ancestry, two African-American males and one woman of European ancestry,” according to the paper the researchers published in Nature Neuroscience last year. They found a surprising commonality in how genes are expressed in the brain: there are just 32 different patterns.

In addition to the Allen Institute, researchers came from institutions all over the world, including Edinburgh University in Scotland; Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands; the University of California, Irvine; the California Institute of Technology; the University of Maryland; the Gonda Research Center at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine; and the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore.

And yet they all agreed on something that challenged long-held notions about the complexity of the brain.

“The number of combinatorial possibilities for these genes should be enormous,” Michael Hawrylycz, one of the Allen Institute’s researchers, told Arlene Weintraub at Forbes. “But what we find is that these patterns are very stereotyped, in the sense that almost all genes look like one of these 32.”

(To understand a bit more about how the Allen Institute uses donated brain tissue to develop its brain atlas, you can read my last post. There’s also a paper on it in Nature from 2012.)

So why does it matter that the brain has fewer genetic patterns than previously thought? It opens up the possibilities for new approaches to diseases old and emerging. The paper is only two years old and already has been cited in research related to autism, ALS, and Parkinson disease.

In a related finding, the research team discovered that the gene patterns related to many important diseases were not found in mice brains.

As NPR’s Jon Hamilton put it, “The discrepancy could help explain why brain drugs that work in mice often fail in people.”

That points to a harder road for those building on this discovery, though. Mice experiments, of course, are cheaper and easier than those using humans. If we can’t study mouse brains to understand all of these 32 genetic patterns, we are likely looking at a much longer time to develop preventive drugs, and other treatments.

From a research perspsective, human brains are scarce. Ben Barres, a professor of neurobiology at Stanford Unversity’s School of Medicine, told Hamilton, "It's actually very hard to get human brain material that's in sufficiently good condition to study."

This points to another reason why the Brain Atlas project is so important. It is expanding the utility of every brain donated by mapping it and making the revealed data available to everyone.

Next: Brain maps show changes as we age.

Related post

Mental mapping: Deep brain science points to better mental health