Two Virginia cities aim to reconnect neighborhoods isolated by long-ago highways

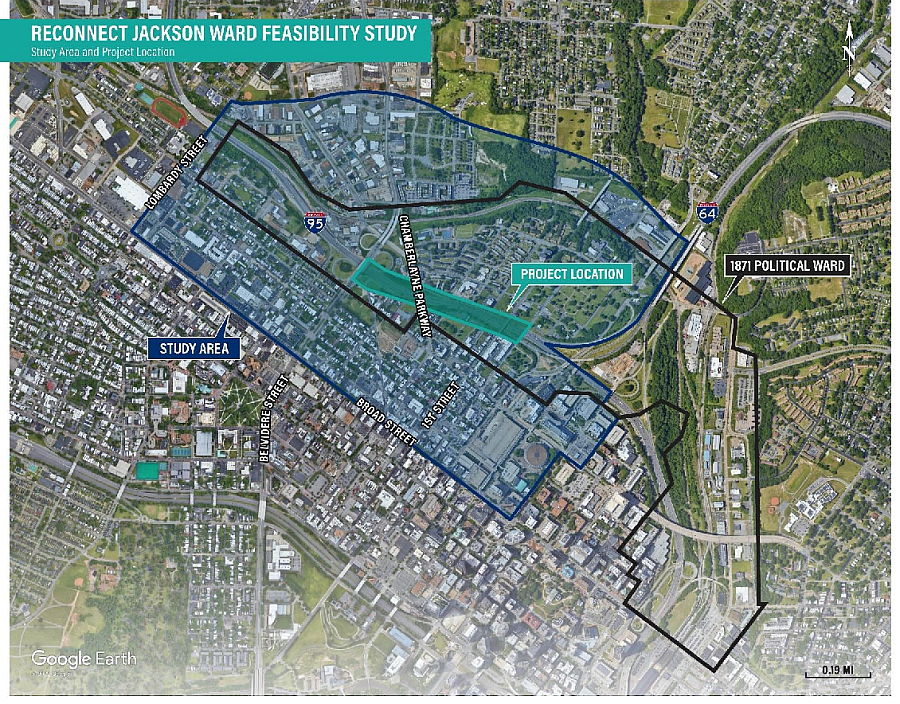

This overview encompasses Jackson Ward and surrounding neighborhoods in Richmond, Va. Generally, it extends from the Belvidere Street Bridge over I-95/64 to east of the North First Street Bridge over I-95/64.

Reconnect Jackson Ward Feasibility Study

The Jackson Ward neighborhood in Richmond, Va., was once known as the Harlem of the South.

That changed in the 1950s when the capital city greenlighted a plan to build Interstates 95 and 64 through the historically Black community. Construction displaced 7,000 residents and 1,000 homes and businesses. The community still exists as an “island” that is a shadow of its former self.

Ninety-two car miles to the east, something similar happened to Tidewater Gardens, a large public housing project built in Norfolk in the early 1950s. Residents, most of whom are Black families, became isolated by the “spaghetti bowl,” a 14-lane wide jumble of I-264 ramps and interchanges built between 1962 and 1991.

Highway projects designed to rush traffic through their urban core aren’t all these two Virginia cities have in common.

Earlier this year, both were among 40-plus cities nationwide that received significant planning grants from Reconnecting Communities, a new program of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

President Biden has made a commitment to advancing equity. This program exemplifies the administration’s effort to honor that pledge. As Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said when he announced the pilot program grants in February: “Transportation should connect, not divide, people and communities.”

Overall, the much heralded bipartisan infrastructure law of 2021 sets aside $1 billion over five years for these endeavors. And the competition for this pilot program is stiff.

Richmond and Norfolk were among the 326 applicants seeking $313 million in planning grants. Separately, 109 applicants sought $1.7 billion for construction projects.

The stories I will be writing with support from the Center for Health Journalism 2023 National Fellowship will delve into what reconnecting means for people living in these long-isolated neighborhoods in Richmond and Norfolk.

One goal is to help readers understand that “fixing” egregious transportation infrastructure decisions of the past is not done with a snap of the federal government’s fingers. It’s a long complicated process, yet it has to begin somewhere.

Another goal is to expose the related health issues. Planners and builders who began bisecting cities in the mid-20th century touted modernization, not the harms to the physical and mental health of Black neighborhoods across America.

It is well documented that people living near interstate highways suffer from more health problems, including asthma and other lung and heart ailments, because of exposure to particulate matter and other pollution emitted by cars and trucks. A nonprofit group, Virginia Clinicians for Climate Action, has documented the prevalence of these health issues across Virginia. I am collecting pertinent information for the project areas in Norfolk and Richmond.

Both cities are led by Black mayors who have been vocal and strategic about advancing equity.

Richmond is using its $1.35 million federal grant to devise a plan to rebuild and reknit the history and culture of the bisected neighborhood. One option is a new bridge across the interstates to connect Jackson Ward. Another is a more expensive “freeway lid” that would be built over the highways. It would be robust enough to accommodate parks and other cultural amenities adjacent to Jackson Ward.

A common theme that emerged among residents when a team of officials and consultants conducted surveys and community meetings last year was making sure the project would elevate and expand Black ownership, history and culture in Jackson Ward.

That sounds fitting. But the bread and butter of one of my stories is to find out what that actually means and why it matters to the people who live there. What are their hopes? Do they trust the government to achieve those goals? Who is accountable? And will residents be helping to design that future now that the initial meetings with state and city agencies and a host of consultants have ended?

The Norfolk article(s) is likely a bigger lift because the $1.6 million federal grant is just a tiny piece of a more enormous transformation in the works.

While I-264 was rolled out decades ago as a driver for the regional economy of Norfolk and other coastal cities in what’s known as Virginia’s Hampton Roads region, developers ignored how the sprawling highway cut off low-income and vast majority-Black neighborhoods from the adjacent downtown core and its job centers, educational hubs, grocery stores, hospitals, transportation resources and cultural institutions.

Neighborhoods such as St. Paul’s along Elizabeth River waterfront and Norfolk State University (HBCU) bore the brunt of the separation.

What’s at the heart of the story is: Who will benefit once the community is “reconnected?” It’s a key question because the city’s reconnect grant ties into an ongoing and overarching plan by the coastal city to replace deteriorating public housing with mixed-use development. That new housing, built in phases, will be market rate and affordable. As well, a voucher program is designed to accommodate some families displaced when the apartments are razed. Others will be eligible to move to public housing elsewhere in the city.

The goal of that larger plan is to reverse injustices and economic disparities by linking the community to downtown resources, boosting access to public transportation and reducing car speed so the area is walkable and bikeable. But if longtime residents are displaced, where will they go?

Briefly, the plan involves:

Connecting residents of this neighborhood to public transportation and greenways by revitalizing the Elizabeth River waterfront as part of a larger citywide $2.6 billion endeavor to address sea level rise and tidal flooding resiliency.

Replacing 1,680 units of obsolete public housing with a mixed-income, mixed-use walkable neighborhood. In 1947, this is the site where the federal government funded the first all-Black public housing project. More public housing was added in the 1950s when the federal government cleared Black “slums” and mixed-race neighborhoods, part of a pattern of residential segregation ordinances and restrictive covenants.

Monitoring the physical and mental health of neighborhood residents via a city-funded initiative called People First.

On paper, those goals sound noble and just. But I want residents along the Elizabeth River to tell me if the project is being done in their best interest. Is the city promising access and healthy living to one group and then, intentionally or unintentionally, delivering it to a new set of residents – and once again marginalizing a Black community?