Native Americans strive for health against alcohol, chaos and trauma

This is the third part of an occasional series on health disparities affecting Native Americans in Portland. This story focuses on how trauma, alcohol and the chaos they produce undercuts Native American health.

The series Invisible Nations Enduring ills focuses on the often-overlooked minority of urban Native Americans and their enduring health disparities.

Part 1: Portland-area Native Americans burdened by health hurdles generation after generation

Part 2: Portland-area Native Americans take on a diabetes epidemic

Part 3: Native Americans strive for health against alcohol, chaos and trauma

Part 4: A Portland diabetic Native American mother risks difficult pregnancy for fresh start

Part 5: Alaska Native Medical Center a Model for Curbing Costs, Improving Health

A 10-month-old girl takes a nap in the child development center at the Native American Rehabilitation Association's residential

Pearl Scott lifts the baby from the crib and balances the child on her hip, just as someone did to her when she was a baby 20 years ago.

Her mom went through addiction treatment here in the Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest's residential center. Now Scott works for NARA, operated by and for Native Americans. She helps care for the 10 children, all five and under, of parents in treatment.

"The counselors here remember me running down the hall with my mom chasing me," she says.

Addiction is both a cause and product of the cycle of chaos that crushes Native families generation to generation.

"We've had grandmothers, daughters and granddaughters in treatment at the same time," says Scott Buser, NARA's treatment director, sober for 20 years after furious battles with addiction.

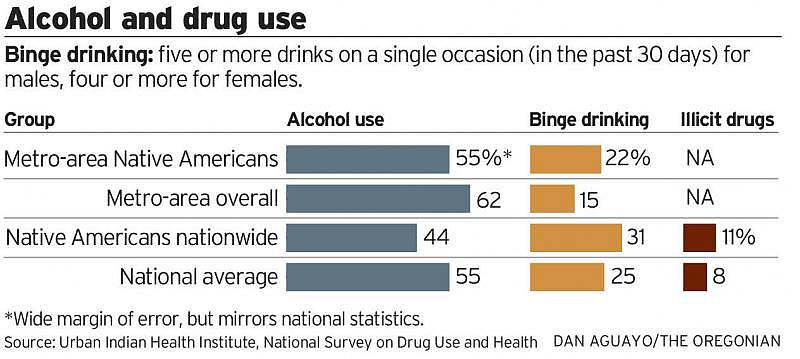

Alcohol and drug use statistics for Natives in the four-county metro area mirror national figures: A smaller portion drink alcohol, but a bigger share abuse it, 31 percent vs. 25 percent of all Americans. Death induced by alcohol or resulting from liver disease is more than double for tribal people in the Portland area.

Addiction also reinforces crushing poverty, which hits nearly half of children and nearly all single mothers in the metro area. One in five Native children in Multnomah County is in foster care, one of the highest rates in the nation.

Government policies that separated Native people from their land, family and customs also made them more vulnerable to alcohol and drugs, tribal health leaders say. Displacement is even more acute for Natives in cities. In the Portland area, home to 30 percent of the 102,000 Natives in Oregon, they are thinly scattered, at once everywhere and nowhere.

A 2010 Census map, however, shows one telling area of concentration in a tract between Portland and Scappoose. This is where NARA transformed a former elementary school into its 70-bed residential treatment program that it runs on a shoestring -- about $100 per patient per day.

It is one of the few Native residential programs in the country that takes in parents and their pre-schoolers – like Pearl Scott was – to hold families together. Last year, eight babies were born to mothers in rehab.

A family affair

Last fall, Elijah Cunningham, 32, and Jenny Bird, 26, shared a room at NARA as they each dealt with their methamphetamine addiction. They entered two days after Bird delivered her third child.

The couple tried rehab before, three years ago when Bird was pregnant with another child. But they left early because Bird had liver problems. Now that boy and their oldest daughter are in foster care on the Warm Springs reservation while they wrestle demons.

"My family is not too big anymore," he says.

Cunningham and Bird, both with Native ties, met eight years ago. Both had dropped high school and picked up drugs. Before long, they were caught stealing checks from mailboxes. Her first offense, Bird spent 10 days in jail. Cunningham had a record and went to prison.

Bird kept using meth for a time. But she had entered treatment when Cunningham was released after 39 months. He soon was using.

"If he is going to get high, then I'm going to get high," Bird concluded and joined him.

Bird again became pregnant. Two days after their daughter's birth last fall, they moved into NARA.

Treatment includes months of group therapy, classes, counseling and traveling the Red Road, 12 steps for Indians based on Alcoholics Anonymous. It also urges residents to connect to their culture. Cunningham prayed in the sweat lodge and joined the talking circle. He helped with the fire starting ceremony for the sweats.

The old ways "helped me become a better father and a better husband," he says.

Bird joined women in their sweat lodge, too.

"When she got out," recalls Cunningham, "it was like she glowed."

Recovering from history

Addictions "are grounded in historical and modern day trauma," says Jackie Mercer, NARA's chief executive officer, who left alcohol behind 19 years ago. Addiction results when people struggle to escape trauma that's knocked them out of balance, she says.

Government efforts to relocate Native Americans, to ban their languages and spiritual and cultural practices, to put their children in boarding schools, to sterilize women and to terminate tribes left a spiritual people strangers in their own land, Mercer says.

"They gave me my first glass of beer when I was about seven or eight."

By age 12, he had a drinking problem. His adoptive mother ridiculed him and sometimes bloodied his nose. By high school, his anger exploded in drunken fights on weekends. While playing football, he says, "I was out there trying to break people's legs."

"No Indians Allowed" signs hung on some restaurant doors in nearby Bismarck. At sporting events, adults would curse him and his teammates, spit on them, tell them to go back to the reservation.

"I figured if they are going to hate me, I'm going to hate them, which is wrong."

He graduated from high school in 1957, three years after the federal government began revoking tribes' sovereignty and claims to reservation land. Douglas McKay, former Oregon governor and U.S. interior secretary, championed termination to give Indians "full and equal citizenship." More than 60 Oregon tribes disappeared, their social services abolished and about 865,000 acres of their land sold. Many headed for Portland.

The federal Relocation Act paid for Archambault's ticket to Los Angeles where he landed a job in Frontierland at Disneyland. He dressed in Indian regalia and paddled a canoe full of tourists as it moved on rails through a manmade lake.

Over the years, he married, assembled planes at Northrop Aircraft Co., then returned to the reservation. As a policeman there, he saw the horrors of addiction: car accidents, suicides, children burned to death in houses locked by parents out drinking, and intoxicated people frozen to death.

A move to Minneapolis followed, where the couple raised nine children. Archambault worked in carpentry, as a bus driver and other jobs, all the while drinking.

"If I'm dying a like him," he thought, "I might as well kill myself."

Instead, he entered treatment, stayed sober, and earned credentials at the University of Minnesota to be a chemical dependency specialist. Divorced in 1979, he headed to the Northwest. Soon, he was counseling at NARA. He sweated though ceremonies in the lodge, endured the grueling Sun Dance rituals on Mount Hood and found purpose as NARA's traditional culture director.

One afternoon this spring, Archambault, now 74, leads a group session.

About 20 residents stretch out on soft couches, women on one side and men on the other. One young mom pats the back of her one-month-old girl. Archambault wears jeans, a leather vest decorated with patches and beads, and his hair is in a pony tail as he paces before the group. He draws from his own life as he talks about humility, honesty, commitments, responsibility, respect and sobriety.

At times he's tough: "Nobody owes you a damn thing. If you can't enjoy sobriety, your are not doing something right."

He's also philosophical. "Death is smiling at us everyday. All we can do is smile back."

And hopeful: "Once I understood where the anger was coming from, then I didn't have to deal with that anymore. I can promise things will get better for you."

Healing in culture

NARA opened in 1970 solely to address alcoholism, but today provides an array of mental, social and medical services. Residents cite the cultural connection more often than any other factor as the service that helped them most in their recovery, Mercer says.

"It is a question of becoming more in tune with their identity," she says. "Culture is about values; it teaches a way of life."

An Oregon Health & Science University study in 2010 found that 51 percent of NARA residents complete treatment, compared to a national average of 42 percent of Native Americans in residential treatment.

Native and non-native health professionals agree traditional ties provide psychological and practical physical benefits. While government long tried to extract culture from Native lives, now initiatives include it. The 2007 federal Indian Country Methamphetamine Initiative, for example, encourage "culture-based" treatment and prevention.

Earlier this month, 18 people, most of them Choctaws, walked portions of the Trail of Tears,where the government force-marched their tribe to an Oklahoma reservation 181 years ago. The group focused on "what does it mean to be Choctaw and healthful in modern times, and how can we commit to the next seven generations?" says one walker, Karina Walters. She is a professor and head of the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute at the University of Washington.

Rather than dwell on suffering, she says, they thought about the source of resiliency and humor in their people, and about traditional health practices.

"That is a much more healthy place to be."

The Coin Ceremony

Back in January, counselors, residents and their families sit in a large circle in the old school gym at NARA. In the center, four men and three children pound on a big drum. A red road on a mural curves to a bright horizon.

Each of the 11 residents will leave with a NARA coin symbolizing a new life without drugs and alcohol. Among them are Jenny Bird and Elijah Cunningham, who sit with their three children and relatives.

Cunningham gives her a long hug.

"I've learned to respect myself," he says. "The only person who can defeat me in my recovery is myself. I'm not asking for much, just a chance for life, and that is what you gave me. I have a Creator, and I have a family now."

An unasked question hangs over the circle: Will Cunningham and the other graduates stay sober? NARA statistics suggest most will. If they relapse, they will be welcomed back.

NARA has helped Cunningham and Bird get into a state-subsidized apartment near Gresham. Cunningham will look for work, probably construction, while he and Bird continue as outpatients. Someday, he says, he'd like to go back to school and become a counselor for a program like NARA's.

When her turn comes, Bird steps up to a microphone and speaks in tears.

"This is my second time around here," she says. "This time I feel like I got it. I got my kids. I got my family. I've got everything I need here."