Part 3: SF’s Homelessness Department Has a Billion Dollars, and Brings Up Almost as Many Questions

This is the third story by Kristi Coale, a 2020 Impact Fellow, in a four-part series investigating San Francisco’s challenges caring for its unhoused people during the pandemic.

Her other stories include:

Part 1: A homeless family in SF lives in housing limbo, while more city-funded apartments sit empty

Part 2: For SF’s Homeless, A Permanent Home Is the Ultimate Goal. The Fight Is How to Get There

Building Homes for SF’s Homeless Is Hard. Providing Mental Health Care Is Even Harder

SF’s Big Street Count Is Coming Back, But Homelessness Fixes Require Deeper Reform

Monica Steptoe is director of Jelani House, a shelter for unhoused pregnant and postpartum mothers in the Bayview. Getting a green light from the city’s homelessness department to let mothers move in off the streets can be “like pulling teeth,” she says.

(Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Monica Steptoe remembers the January day when she first heard about the young pregnant woman who was living out of her car. She would have been a perfect fit for one of the 10 vacant rooms in Jelani House.

Steptoe runs the house, which provides temporary shelter for unhoused pregnant and postpartum mothers in a Spanish-style former nunnery in the Bayview. Even though she’s the director, Steptoe couldn’t act on her own. She had to wait for the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, or HSH, to send an outreach worker to verify that the woman was indeed homeless.

So Steptoe waited. Three weeks went by, and no one from the department had checked on the woman. “Oh my God, it was like pulling teeth,” Steptoe recalls. For a while, she lost touch with the expecting woman entirely.

Only in the last couple weeks did the city finally reach her and move her into housing. The long delay could have had dire consequences. Housing is health care, even more so for pregnant homeless women, who face higher risk of complications.

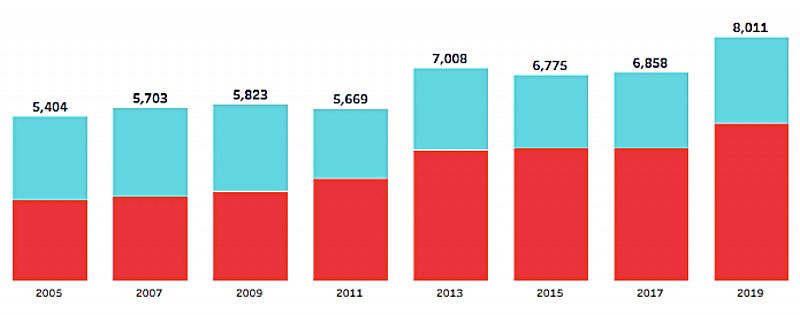

It is also a matter of racial equity. By a 2019 count, the city’s most recent, 37 percent of SF’s homeless population was Black, compared with only 6 percent of its general population, which is the largest disparity among the city’s racial and ethnic groups. These missed connections are not just putting lives at risk; they are also a lost opportunity to build crucial trust between providers and unhoused people, according to Steptoe.

Incidents like this may be hard to take but are not uncommon for providers like the Homeless Prenatal Program, or HPP, which owns Jelani House. They say they receive numerous calls and emails daily from social workers and medical providers asking for shelter for pregnant women and those with infants. They’d like to bring these women in, but the city won’t let them. “When someone doesn’t get to that client in a reasonable amount of time to verify homelessness, then we lose them,” Steptoe said. ”They don’t come back, then we don’t know where they are.”

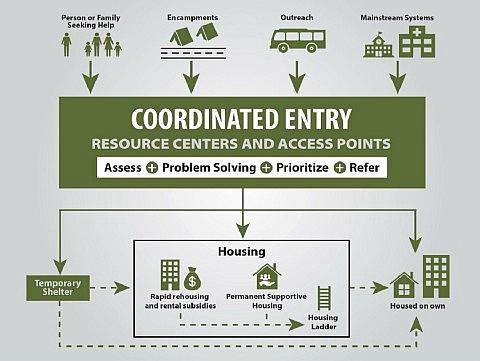

Even more frustrating is that nearly five years ago, the city of San Francisco created HSH to eliminate these errors. The department reorganized the work of several city agencies under one umbrella and with a new mandate: end homelessness by harnessing technology to move thousands of unhoused people more efficiently toward housing and services, which cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Seattle had already been doing for years.

But that was then. COVID-19 not only scrambled the department’s priorities, it has shaken up its leadership and structure — with big changes just in the past week that underscore the turmoil HSH has experienced throughout its short life. Even before the pandemic, HSH’s tech-centric system was having problems, and SF streets were experiencing a shocking increase in unhoused residents.

There have been some successes amid controversies. The agency is now at a critical juncture. By budget, it’s the largest department in the city with no formal oversight, and now for a year running, no permanent leadership. Its interim director Abigail Stewart-Kahn, who took the reins as the city was locking down last year, quit March 18.

What’s more, the city’s emergency COVID Command Center, which is separate from HSH, wants to move the roughly 2,000 people living in shelter-in-place hotels into permanent supportive housing, and has tapped a veteran homelessness advocate to run point. (The move was first reported in the SF Public Press as the creation of a new office taking responsibility away from HSH.) But it’s not clear how much responsibility or budget will shift. HSH’s budget, which has grown 250 percent since 2016, began the current fiscal year at $852

Before and after: In the early days of HSH, director Jeff Kositsky’s presentations often showed how the new system would streamline access to services.

Despite the turmoil and outsized expectations, this could be the right time to make a real difference —not just for the city’s most vulnerable, but also for the residents and business owners who want cleaner streets and humane outcomes. Can the department deliver on its promise to end homelessness, or even put a significant dent in the problem?

To answer these questions, we have talked to dozens of stakeholders to sort out what many officials, observers, and advocates say are HSH’s chronic problems: understaffing, poor information sharing, a patchwork of oversight, and challenges keeping track of money. We will also look at what the department has gotten right in extremely difficult circumstances, and what lies ahead in SF’s fractious post-COVID recovery.

Lee, Breed, and COVID

In August 2015, San Francisco had plenty of housing and homelessness issues. Affordable housing was scarce, evictions were on the rise, and large tent encampments dotted the city, including the downtown streets where Mayor Ed Lee and his hospitality team were planning a big party for the upcoming Super Bowl 50. “We’ll give you an alternative,” Lee told the tent dwellers. “But you are going to have to leave the streets.”

The alternative came in May 2016, when Lee announced the new Homelessness and Supportive Housing Department and set an ambitious goal to “end homelessness for at least 8,000 residents in the next four years.” It hinged on two main strategies: aggressively moving people indoors, and having a range of places to house them, based on their needs. For its director, the mayor tapped Jeff Kositsky, who had been leading a shelter-and-service organization for homeless families.

When Lee died suddenly in December 2017, London Breed stepped in as mayor, pledging 1,000 new shelter beds and more specialized invitation-only shelters called Navigation Centers. But she campaigned against Proposition C, a business tax that would roughly double the city’s homelessness budget, angering many advocates and providers. (Prop C won anyway.) Kositsky, for his part, was catching heat from several supervisors while Breed was touting successes: more shelter beds, fewer tent encampments. In March 2020, Kositsky resigned his post to take over a smaller homelessness-focused group, the city’s Healthy Streets Operation Center.

A year ago, when the deadly coronavirus was spreading, people in crowded group shelters and tents were in greater harm’s way. Hotels, now empty of visitors, seemed a good alternative, but the mayor and supervisors fought over how many rooms to rent and how fast to fill them.

The debate over hotels has cooled for now. Federal and state dollars will reimburse most, if not all of SF’s COVID hotel spending. (Those still in the hotels — 1,882 as of March 23 — are now a city priority to move into permanent supportive housing.)

Yet the influx of cash and the management musical chairs make a high-profile call for reform issued last year even more urgent today.

Getting audited

An August 2020 report by the city’s Budget & Legislative Analyst, or BLA, which works on behalf of the Board of Supervisors, laid bare a host of chronic problems at HSH. Yes, COVID struck in the middle of the months-long audit, putting the department in emergency mode under intense pressure and rapidly shifting health rules — and by moving fast to put infected folks in hotels, HSH likely gave local hospitals vital breathing room, according to UCSF researchers.

Nevertheless, the crisis conditions and impromptu efforts didn’t excuse what came before the pandemic, the report charged. The department, four years in, “has not yet changed the trajectory of the increase in homelessness,” it read.

The BLA’s blast echoed a narrower 2019 report from the SF controller (a branch of the mayor’s office), and it added fuel to demands for reform. “I think it’s pretty damning,” District 6 Sup. Matt Haney told the SF Chronicle. “How are we spending more and getting less?”

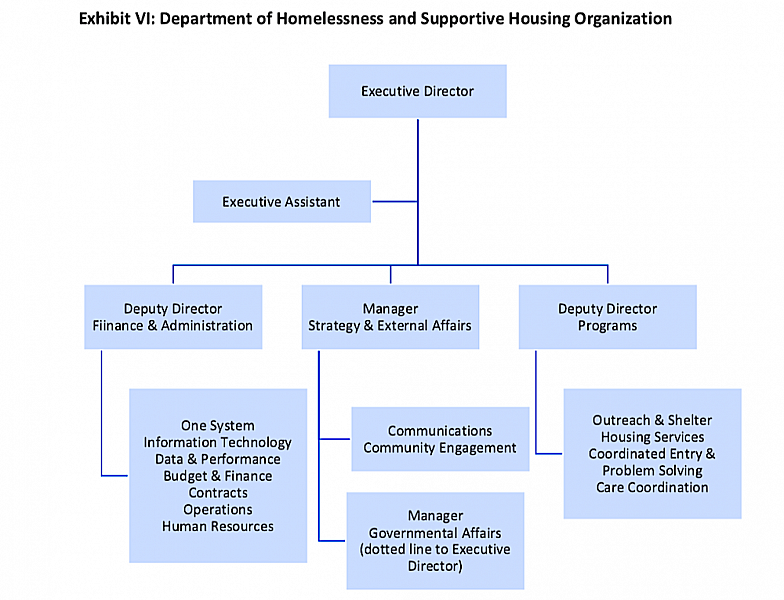

The report focused on four major problems: the monitoring of providers and contracts, chronic understaffing, poor data management and tracking, and no formal oversight. Of all the issues, understaffing remains the linchpin of HSH’s problems.

Without more people in the right places, HSH can’t properly track and help unhoused people and can’t properly manage the network of 59 nonprofits — Episcopal Community Services, Glide, Hamilton Family Services, Larkin Youth Services, and many others — that run the city’s 350 programs for homeless services, shelters, and supportive housing.

From those providers’ view, the department’s organizational chart is hard to fathom. This isn’t an esoteric complaint: There are real-world consequences when providers don’t know who to contact to, say, expedite the move of a pregnant woman living out of her car into Jelani House.

The lack of clarity became an issue not just for providers, but also for Haney and the mayor’s staff, who wanted an org chart. One finally emerged only after BLA started digging in with its audit. Even then, it was bare-boned (see chart), which was all the more troubling because Kositsky himself, in 2018, had asked the city controller to evaluate whether the department had enough people to meet upcoming demands, like new shelter beds.

Bare bones: This is all the auditors came up in 2020 with after several parties requested a deeper look at the structure of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. (SF Budget & Legislative Analyst)

HSH’s high turnover also leads to confusion or paralysis when one staffer gives information that conflicts with the person they replaced. “It gets unclear who you call the further up you go,” says Rachel Stolzfus, housing director for the Homeless Prenatal Program.

For an agency that hasn’t had a permanent leader running point during the pandemic, it’s hard to imagine how communication will improve now with Stewart-Kahn stepping down. Her successor, Sam Dodge, worked at HSH early on but is just a stopgap. Dodge “will move over from his current position at Public Works to lead the department until a replacement is found,” the mayor’s office said in the final paragraph of the announcement on the leadership change.

When The Frisc asked Haney about the transition, he called it “a huge setback. … We’re basically going from interim [director] to someone who has much less experience than interim at the most important time.”

Stewart-Kahn — who was handed HSH’s reins when Kositsky left last year, but never lost the “interim” title — acknowledged this very problem of inexperience, including her own, among senior staff in detailed comments that were part of last year’s BLA report. “Five out of seven members of this team have been in their positions for much less than one year,” she wrote.

Still, Stewart-Kahn cited 18 accomplishments from HSH’s inception, such as the creation of a system to track empty supportive housing. But she ultimately agreed with BLA’s recommendations for remedies.

Staffing: Keeping track of contracts

So what has the department done to deal with its woes and absorb the recommendations that BLA laid out last year?

Let’s start with staffing. The BLA report advised HSH to work with the mayor’s budget director and the SF Department of Human Resources to quickly fill key positions, particularly its own human resources division. (In other words, hire some people who hire.) Department spokesperson Deborah Bouck says it has made progress: “HSH has staffed up the HR team to support additional hiring of vacancies that has been a continued challenge since our inception.”

Bouck says the overall vacancy rate is now 14 percent. The department’s 23 open positions include two contract analyst vacancies that have been posted since September.

That’s notable because the BLA report urged HSH to improve oversight of its myriad contracts with service providers. It wanted to see clearer goals set for HSH contractors, along with a documented review of each contract “at least annually” to check if providers are hitting their goals. (BLA also recommended using standardized forms for contracts.)

It’s hard to do all that without contract analysts. HSH’s Bouck said the department and the controller’s office are planning “to launch a work group to carry this critical work forward.”

Now comes news that a group outside HSH will move shelter-in-place hotel residents into permanent supportive housing, muddying the waters further. Organized under the city’s COVID Command Center, the unit’s leader is Chris Block, former director of the nonprofit Tipping Point Community’s Chronic Homelessness Initiative. Block will report to the city’s emergency department chief.

When the pandemic began, HSH employees were reassigned to the command center to help activate and staff the hotels. Block told The Frisc weeks before he was tapped for the new city post that the emergency reassignment hurt HSH’s long-term goals. “The single-minded focus slowed down the whole system,” he said.

Departmental staffing woes had already resulted in money mismanagement. With the department’s budget at more than $1 billion over the next two years, it’s unsettling that the BLA report uncovered shoddy contract oversight. For example, its report flagged $26.5 million in federal, state, and city funds that were received but went unspent in the 2019–20 cycle, about 7 percent of the department’s $364 million budget that year.

This raised enough concern that federal Housing and Urban Development worked with HSH recently on a review. HSH officials have said publicly it was not a punitive audit. (The Frisc requested documents related to the audit but had not received them as of press time.)

The Biden administration’s promise to fund the shelter-in-place hotel program frees up $15 million to $18 million a month. That cash adds to the hundreds of millions of dollars per year from 2018’s Prop C business tax, finally released by a court decision last year, and bond money approved by voters last November, that the city can now spend on homelessness programs. More money won’t help, though, if HSH doesn’t have the mechanisms in place to spend it correctly.

Sharing information: ‘The system is broken’

At the February 1 meeting of an advisory panel called the Local Homelessness Coordinating Board, HSH director of housing services Salvador Menjivar reported an eye-opening number: There were 766 vacant units in the city’s supportive housing system, a key component of the strategy to move people off the streets. Menjivar said almost 40 percent were only temporarily empty due to maintenance and such, which was cold comfort to Swords to Ploughshares director Tramecia Garner and other providers.

“The vacancy issue predated COVID, and we have no updates from the city on how to move referrals to providers,” said Garner, who expressed exasperation with HSH for focusing on small details while issues like the housing vacancies grow worse. (The current total was 58 percent higher than the 484 vacancies HSH reported last September.)

With hundreds of people like this family willing and able to move, their predicaments weren’t just a sign of HSH being overwhelmed by the pandemic, providers said. It was something deeper: an unwillingness to accept help matching unhoused people with open housing faster. “We’re experiencing long delays,” said Sara Shortt of the Community Housing Project.

‘You used to be able to pick up the phone, talk to someone you knew, and get people off the streets. Now it’s hard because they don’t treat us like they trust us.’ —Homeless Prenatal Program executive director Martha Ryan

Sheylis Arroyo with her baby at Jelani House. Delays in the city’s bureaucracy have kept other women from moving into the house, even when there are open spots. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Moving power away from providers was one of Kositsky’s priorities when he started HSH four years ago. “We’re trying to change the way business has been done for the last 20 years,” he said to The Frisc in 2019. “We used to be a nonprofit-centered city. We need a client-centered system.”

HSH and the city as a whole still depend heavily on providers to address homelessness. So efforts to shift away from the nonprofits have brought the city a lack of trust, several providers told The Frisc.

“In the old days, you used to be able to pick up the phone, talk to someone you knew, tell them what’s going on, and get people off the streets,” said Homeless Prenatal Program founder and executive director Martha Ryan. “Now it’s crazy. It’s hard because they don’t treat us like they trust us. What do they think we’re going to do? We just want people not to have to sleep in cars.”

Tipping Point’s Block, before he joined the city, said that distrust on all sides — the Board of Supervisors, the mayor, HSH, and providers — is “a huge detriment.” The city’s ability to meet the needs of its most vulnerable residents depends on all parties to set aside differences and collaborate.

Before the pandemic, the various parties were getting together to do just that, despite the acrimony. But it wasn’t easy; a brief period of problem-solving only came about from a failed attempt to force HSH to be more accountable.

Oversight: How much is enough?

From August 2019 to February 2020, HSH officials, homeless service providers, supervisors, and even Mayor Breed from time to time would gather once a month around a large conference table at City Hall to hash out differences. The meetings actually grew out of a contentious compromise. Chafing at HSH’s special status, with no formal oversight like other major city departments, Sup. Haney had pressed for an oversight commission and threatened to take it to voters on the November 2019 ballot.

Breed and the members of the Board of Supervisors had been battling all 2019, and the mayor pushed back, arguing that a commission would stymie HSH’s ability to add shelter beds and offer services. Haney couldn’t convince enough supervisors to place his measure on the ballot. While the mayor strengthened her grip on the homelessness policies, she offered an olive branch with the informal gatherings.

As some attendees now tell it, the working group was a safe harbor for dialogue and coming up with solutions — where, for example, the problem that pregnant women were not eligible for family-based shelters was fixed. “Our goal was to bridge the gap between the mayor, providers, and staff at HSH and create a venue for sharing what they were advocating for,” said Haney’s legislative aide Courtney MacDonald, who facilitated the gatherings with one of the mayor’s aides.

HSH accountability was still spotty, but at least the working group opened a channel for sharing information. Once the pandemic hit, however, the group meetings stopped.

Good oversight is conducted by people who understand the issue. Bad oversight lets politics interfere. ‘It doesn’t give people the opportunity to be flexible.’ — Tipping Point CEO Sam Cobbs

Now it’s an open question who is keeping an eye on HSH. When The Frisc recently asked Haney if he still wants an oversight commission, he hedged. “People are going to feel like Matt Haney thinks the solution to everything is a new commission. I don’t believe that,” he said.

The supervisors do have a government audit and oversight committee, but it hasn’t looked into HSH since the pandemic began. The Frisc contacted its three members, Connie Chan, Rafael Mandelman, and Dean Preston for this story, and only Mandelman responded. (We also asked every member of the board for comment about HSH and accountability; several did not respond. Aides to Sups. Hillary Ronen and Shamann Walton referred questions to Haney’s office.)

In the last six months, Haney has held two hearings just on the housing vacancies. He asked Stewart-Kahn in September how much revenue HSH has lost due to the vacancies. In late February, she responded that the department hadn’t had the resources to do the analysis.

As head of the board’s Budget & Finance Committee, the D6 supervisor is in position to push for more, as he did March 3 in pressing Stewart-Kahn about contracts and spending, among other items. Haney asked whether “anything has changed in transparent and effective contract oversight.”

Stewart-Kahn offered that the department — which has over 230 agreements, 22 forged in the COVID emergency — had moved to “performance-based contracting” that focuses on the outcomes a provider achieves.

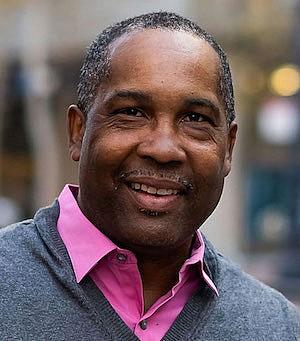

Sam Cobbs: Drawing a distinction on oversight.

At the same time the vacancy problem has not improved, and that’s why board hearings alone won’t work, according to Haney. “This is a clear example of the consequences of a department not having a direct oversight body that holds public meetings, sets strategy, and pushes them to deliver results,” he said.

One service provider had words of caution about looking over HSH’s shoulder. “Some oversight, depending on the type, would be helpful,” said Tipping Point CEO Sam Cobbs, who drew a distinction between good and bad oversight. The former is “conducted by people who understand the issue,” while the latter, he noted, lets politics interfere and bureaucracy get in the way. “It doesn’t give people the opportunity to be flexible.”

An example of the good type includes the Local Homelessness Coordinating Board, which includes people who have experienced homelessness, like Del Seymour. The HSH director is required to attend the meetings and provide requested information. (It’s where Salvador Menjivar revealed last month that the housing vacancy problem had gotten worse.)

Co-chair Seymour has downplayed the authority of the board, saying “there’s not a real oversight relationship.” Nevertheless, during COVID the advisory panel has become a regular venue to raise serious issues and grill HSH officials, and it has lengthened meetings to accommodate a growing agenda. As for results? Seymour’s plea in February for HSH and providers to work out a solution for the housing vacancies brought about a pilot program.

With Seymour’s board, supervisor committees, and yet another panel that recommends how to spend the hundreds of millions of Prop C tax dollars, Mandelman said he thought that ”the department has plenty of oversight.”

“I don’t think an oversight commission would resolve the main issues of HSH,” he added.

‘Not a work of genius’

One area where the icy relationship between providers and HSH may be thawing is housing vacancies.

Housing providers Dish and Brilliant Corners are participating in a pilot that aims to cut wait times for supportive housing from five months or more to 45 days or less, by giving the providers more leeway with housing referrals. This would be a major improvement over the vacancy-riddled system made worse by the department handing providers one referral at a time, according to Dish co-founder Doug Gary.

“Doing multiple referrals is not a work of genius,” he said. “It’s very practical, and we can fill the vacancies quickly.”

With ambitious plans to expand supportive housing, the department needs to work differently, said Block: “We’re in a period of massive scaling. You can’t just make referrals the same way and work the same way.”

Moving slowly is a hallmark of San Francisco’s bureaucracy; look at the permit process for starting a business or building anything. The lack of urgency can be deadly when people who should be housed are stuck on the streets. There are signs of impatience with red tape and delay, from voter-approved small-business reform and an easing of regulations on some affordable housing to a state ban on appeals that slow the construction of Navigation Centers.

The needle to thread is to reform HSH, be nimble and directed, and save lives, all with guardrails that protect public and stakeholder trust and the hundreds of millions of dollars the department controls. After all, in the name of speed and efficiency, disgraced former Department of Public Works director Mohammed Nuru was given carte blanche to award construction contracts— including one at Jelani House —without any oversight.

A Public Works contract to renovate Jelani House was part of the ongoing City Hall corruption scandal. (Photo: Pamela Gentile)

Perhaps the biggest area for reform should come from City Hall’s two camps, according to Mandelman. With the mayor fighting for more shelter beds and supportive housing, and with the supervisors looking to make the emergency hotel program permanent, “there’s not a clear message from policy makers,” he said. “If this department is going to be successful, it would help if we could achieve a common set of goals.”

Moving unhoused people into permanent supportive housing is clearly a top goal, as Chris Block’s new role at City Hall shows. But San Francisco’s housing shortage won’t magically ease up. Beyond the 2,000 people in the shelter-in-place hotels, there are thousands more unhoused in SF, not to mention those whose precarious lives place them one paycheck or bad break away from the streets.

The trials of the past five years, with decision-making power centered under one roof, haven’t done nearly enough. The city will need creativity, flexibility, and accountability, not just money, so that we can start marking real progress — by putting thousands of heads under thousands of roofs.

Kristi Coale (@unazurda) is a San Francisco-based freelance writer and radio producer for various outlets, including KALW’s Crosscurrents and the National Radio Project’s Making Contact. She reported this story as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2020 Impact Fund fellow.

[This story was originally published by The Frisc.]