Youth obesity rates holds steady, even as youngest make gains

Less than a quarter of kids get the recommended 60 minutes of exercise a day.

Earlier this year, news broke of a welcome respite from three decades of depressing news on childhood obesity.

Among 2- to 5-year-olds, obesity rates dropped 43 percent from 2003 to 2012, according to federal health survey data. And that encouraging finding was on top of a report from 2013 that found obesity rates among low-income preschoolers fell in 19 states and U.S. territories from 2008 through 2011.

Those are two very encouraging pieces of news for the struggle to curtail childhood obesity rates, which have more than tripled since 1980. The fact that gains are being seen among such young children is particularly heartening, since overweight or obese preschoolers are five times more likely to grow into overweight or obese adults, according to the CDC.

But those early childhood decreases are only part of the picture, as a recent report jointly issued by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and the Trust for America’s Health makes clear. The report finds that while some groups have indeed experienced decreases, overall childhood obesity rates have held steady since 2003. The good news is that the rates have stabilized and are not rising. The bad news is that the rates have stabilized and are not dropping.

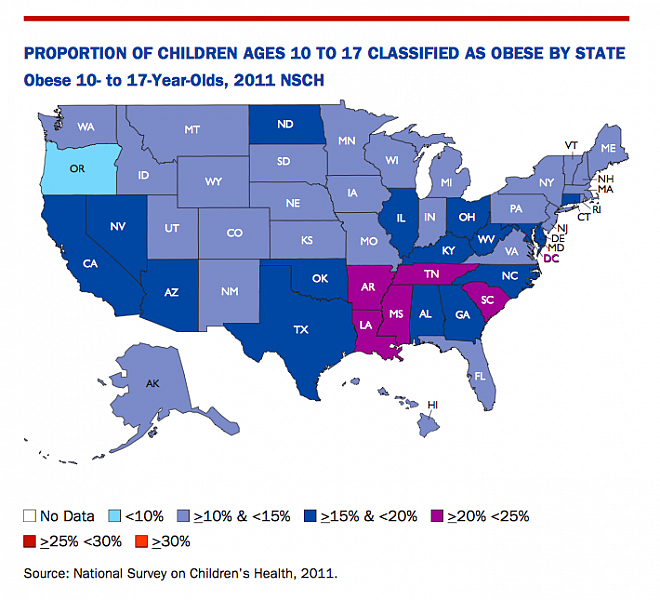

The report also documents the persistence of some glaring racial and geographic disparities, with minority children and kids and teens in the South suffering from obesity at much higher rates than their peers elsewhere.

First, the big picture view: Overall, about 17 percent of children ages 2 to 19 are obese. When overweight children are added to the mix, the figure rises to 32 percent.

But when those figures are broken down by racial group, the disparities stand out: 22.4 percent of Latinos ages 2 to 19 are obese, 20.2 percent of black youth and 14.3 percent of whites. Among that same age group, black boys are three times as likely to be severely obese (10.1 percent) as white boys (3.3 percent).

Gaps emerge along geographic lines as well. Of the top 10 states with the highest rates of obesity among 10- to 17-year-olds, seven are in the South. Mississippi leads the nation among this age group, with a 21.7 percent youth obesity rate, while Oregon takes top honors at the other end of the spectrum, at 9.9 percent.

Since obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes, it’s not surprising that the southern states lead in the nation in rates of type 2 diabetes, which is on the rise among youth. In youth under 19, type 2 diabetes increased a whopping 31 percent from 2001 to 2009, according to the report.

Where do we go from here? The policy recommendations in the report will all sound familiar:

Increase physical activity before, during and after school; offer nutritious food and beverages at school; make healthy, affordable food prevalent in all communities; ensure healthy food and beverage marketing practices; engage health care professionals to more effectively prevent obesity both within and outside the clinic walls, in collaboration with community partners; and intensify our focus on prevention in early childhood.

One might think we should just isolate what’s responsible for the obesity decreases among young children and build on those successes. But as the New York Times’ Sabrina Tavernise reported earlier this year, even experts can’t agree on what’s working. “There was little consensus on why the decline might be happening, but many theories,” she wrote.

Those theories include fewer calories from sugary drinks, more breastfeeding and families buying healthier food due to changes in the food stamp program. Or perhaps it’s the collective impact of a bunch of different policies and programs targeting obesity through fitness and healthier eating.

Most agree that getting kids to exercise more is essential, but doing so is an enduring challenge. Experts recommend about 60 minutes of physical activity a day, but a report released this spring found only about a quarter of kids 6 to 15 met that benchmark. P.E. standards issued by states tend to be lightly or unevenly enforced.

Where kids live can matter as well. A study published in March found that counties with more access to nature trails and public forests tended to have more active kids and lower rates of obesity. That, of course, is of little help to inner-city kids who lack easy access to safe outdoor areas, let alone natural lands. A 2012 research brief found that the kids at greatest risk for obesity are least likely to have school recess.

Healthy eating is the other half of the equation, and for policy makers, perhaps the easiest point of entry when it comes to improving kids’ nutrition. According to the RWJF report:

Children and teens in states with strong laws restricting the sale of unhealthy snack foods and beverages in school gained less weight over a three-year period than those living in states with no such policies.

Stricter school lunch requirements were ushered in by the 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, but the federal legislation came under attack in Congress in May. House Republicans and the School Nutrition Association sought to roll back or allow schools to opt out of the new standards, which call for healthier foods with more whole grains and less sodium.

First Lady Michelle Obama has championed the 2010 legislation and is now leading the battle to keep the healthier standards in place. The ongoing fight is expected to return to Congress this fall, but with the addition of 500 former military leaders backing up Obama’s defense of the tougher school rules.

Photo by Victoria Harjadi via Flickr. Graphic from RWJF/The State of Obesity: 2014.