How letters from prison helped me develop sources and build trust with incarcerated youth

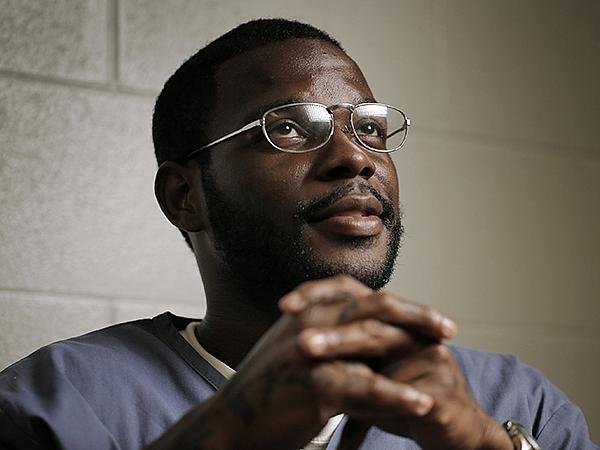

Aaron Wright’s story was part of Tessa Duvall’s larger look at the unusually high number of youth homicides in Duval County.

(Photo: The Florida Times-Union)

Not every journalist looks forward to seeing a “mailed from a correctional institution” stamp on their mail, but I do.

Such a sight has led to me busting out my happy dance moves in the newsroom on more than one occasion. I even jumped for joy on one particularly good day when 14 pieces of prison mail landed in my mailbox.

In 2017, I set out to understand why my community at the time, Jacksonville, Florida, had so many young people getting locked up for their role in killing someone. Duval County, known for years as Florida’s murder capital, also led the state in kids who killed.

Over the span of a decade, 73 Duval County children were arrested in cases of murder and manslaughter. Adjusting for population differences, no other large county in Florida has a higher rate of minors arrested on these charges than Duval.

I wanted to know: Why?

To understand such a complex problem, I knew I would no doubt need to call on criminologists and service providers who worked with kids, pore over court records and analyze years of data sets and trends.

But what the story really needed — and what it would have failed without — was the voices of the kids who took part in these crimes.

Working with my engagement coach, Terry Parris Jr., then at ProPublica, we developed a plan in which I would survey young offenders from Duval County who were serving sentences in Florida prisons for murders or manslaughters. We discussed how the survey would be crafted, but perhaps more importantly, how I’d take steps to get anyone to take the survey in the first place. Asking someone to pour out the most intimate details of their lives wouldn’t have been a great opener, and would have no doubt led to an abysmal return rate.

Using a data set of inmates from the Florida Department of Corrections, I was able to filter down the entries to the incarcerated people who met my criteria: incarcerated as a juvenile, serving time for murder or manslaughter, and from Duval County.

Then it was time to introduce myself. To do this, I wrote letters to all 103 of these incarcerated young people from Duval County and explained who I was and what I was trying to accomplish:

“It must be strange to get this letter from a reporter so randomly, so let me explain why I’m reaching out: I am working on a long-term story that seeks to understand why so many kids are committing homicide in Jacksonville. So, I’d like exchange letters with you in order to learn about your life. My goal is to understand your upbringing, your childhood and the things that affected you growing up here in Jacksonville.

The goal is to understand what happens to the kids who are most vulnerable in the community before they are permanently tangled up in the adult justice system. I believe that if adults understand the full extent of problems, then they can find the necessary solutions for them. This is why I am reaching out to every single person from Jacksonville who is incarcerated due to a situation like yours.”

A form letter, sure, but it was sincere. I also included a story I’d written about Terrence Graham, the Jacksonville man whose landmark Supreme Court case, Graham v. Florida, overturned juvenile life without parole for non-homicide offenses. It was an example of how I approached writing about people in prison, and, I hoped, a way to show 103 potential sources that I wasn’t out to sensationalize their life stories.

It worked. Fifty-seven people wrote me back. Some said they’d known Terrence and liked reading about him. Some were ready to tell me whatever I wanted to know. Some sent back their autobiographies, no questions asked.

But some still needed convincing. They remember how they’d been written about decades earlier, as monsters and evil beings. They wanted to know why they should help me, a reporter at the very paper that once dehumanized them.

Mostly, though, people just wanted to be heard. These incarcerated people ranged in age. Some were still teens who’d only recently been sent to prison, but others were old men who hadn’t felt listened to or understood in decades. To be listened to without judgment was something that many of them found comforting, and they were honored by it.

These letter exchanges went on for months. In part because I became buried under prison mail and it takes time to write personal responses to 57 letters, but also because using old-fashioned snail mail just takes time. Then consider the fact all the letters must be opened and reviewed by prison staff before they can be delivered to the recipient.

As I was getting people to open up to me and agree to take the survey, I was still crafting that survey. I knew I wanted each survey to feel like its own interview, and I knew I wanted to be able to create my own unique data set from the findings.

The survey went through six revisions before settling on the final 50-question version that was sent out to my incarcerated sources. I asked for help from a psychology professor, a criminology professor who works in prisons, a formerly incarcerated youth advocate, a child psychologist, a pediatrician and Terrence Graham himself.

The survey was a mix of common trauma assessments, like the ACE Score, and questions that just needed answers, like where they got their firearms and were they alone at the time of their crime?

Some of the best revisions were things I never would have thought of without the input of the experts who helped me: Use this simpler word instead of that one you have now. Add in some more positive questions so getting to the end of the survey doesn’t feel so heavy. Make this gender neutral.

The best revision, I believe, came from Terrence Graham, who suggested I ask if their crime was the result of another crime, or a street beef gone wrong. That would become a huge point in the reporting later: these kids didn’t set out to be killers; they typically set out to rob or steal.

Throughout the letter-writing process, I lost some respondents along the way. Attorneys advised them to not speak with me, or they lost interest or misplaced my letter.

In all, 25 people agreed to answer my survey.

It was a small, but mightily important, data set that revealed the depth of trauma, violence and despair in the lives of the Jacksonville young people who found themselves in prison.

Some key findings:

-

84 percent said they've been shot at and 72 percent had witnessed someone get shot.

-

60 percent reported emotional abuse at home and 84 percent said they lived with someone who was a problem drinker or who used street drugs.

-

At least 12 remembered being held back a year or more in school and six said they were placed in special education classes.

These points were so powerful because they weren’t anonymous subjects in an academic survey done in some other state — they were real kids from our community that suffered tremendously before they caused tremendous suffering. Readers got to see their faces, know their names and hear their stories.

With the gift of hindsight, there are several things I’d modify if I set out to do this project over again. For anyone else who aspires to crowd-source from prison, I’d recommend the following:

-

Think through the obstacles you may face. Fellow former National Fellow Cary Aspinwall of The Dallas Morning News spoke to me about a similar letter-writing effort she’d used to report her project. A minor tip proved to be hugely helpful: send a self-addressed stamped envelope. Canteen items in prison are expensive, and if it’s a financial burden to write to a reporter, then some people won’t be able to participate in the story. This also means getting acquainted with the rules for prison mail. I thought it was a great idea to use labels for my return envelopes — until my letters started getting rejected because I’d sent an item with an adhesive.

-

Organization is key. With so many letters coming in every day, and notes to take from every single one of them, I had to be meticulous. Each person I corresponded with had a folder in my documents, and the letters were dated in chronological order. I built a spreadsheet that allowed me to track my response date, their response date, their willingness to participate in the survey and input notes and stories from the Times-Union’s archive. Because I was getting hard-copy letters, I decided to organize them using accordion files rather than scanning and saving them all. For me, that was a way to save time. There might be something I need in every letter, but I didn’t need every page of every letter at all times.

-

Hurry up and wait. This is hard for me, admittedly. I like being able to pick up the phone and get clarification from a source right when I need it. With prison mail, answers can take weeks to get. Plan ahead with your writing and publication timetables accordingly.

-

Ask specific, pointed questions, and ask them one at a time. There are several questions on my survey that I wish I had separated from one another or asked in a more direct “yes” or “no” format. For example, I asked the following with three blank lines that followed: “How were your grades in school? Were you ever held back a grade or did you need special help? What were your best classes?” Looking back, I wished I’d asked about special education and being held back as their own yes or no questions. By the time I realized that, it was too late to modify the survey as they were already in the mail.

-

Be willing to answer as many questions as you ask. Like i mentioned, some people were apprehensive about talking to me. Not only was I a reporter, I was also a faceless stranger in an office miles away. These folks knew nothing about me or my motivations, and some even doubted if I was a real person or just someone messing with them. At least a few asked their mothers to call me and verify that I was real. Others wouldn’t answer any of my questions until I’d answered all of theirs.

Yes, these things slowed the process down, but, building rapport and trust with people takes time. It’s harder when it’s entirely through the written word, with weeks if not months between communication. I recognized that I was asking people to put a lot of trust in me and be deeply vulnerable in our communication. The least I could do was help them feel comfortable in the process.

Read the stories in Tessa Duvall’s fellowship project here.