Under Our Skin: How racism leaves an unmistakable mark on Black Americans

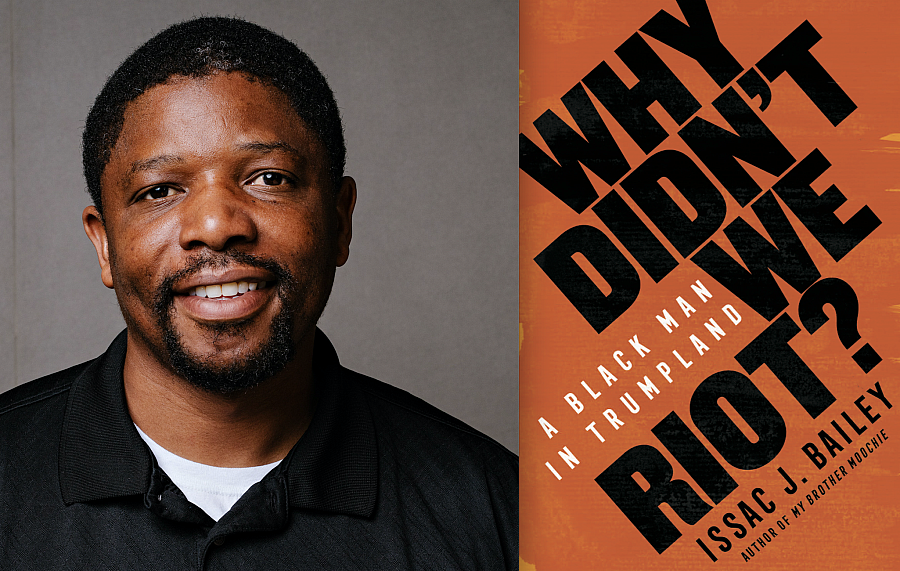

Issac J. Bailey.

I’m only now coming to grips with what it has meant to my soul – and my body – to have been born Black in the Deep South in the shadow of Jim Crow and raise my kids during the era of Donald Trump. I’m one of the fortunate ones because I’ve survived to tell my own story and lived long enough to see science begin to answer questions that have long lingered in my brain. In this excerpt from “Why We Didn’t Riot: A Black Man in Trumpland,” I try to capture that truth.

**

Our bodies, our scars — psychic, emotional, physical — are evidence of a sickness that has been with us since before this country’s founding and, like a virus, morphs and transforms, constantly seeking new hosts to remain alive no matter whom it maims or kills. As a black man from the South, my body bears proof of white supremacy’s persistence and limitations. I’m a carrier of white supremacy in the way I’m a carrier of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, or CIDP, the autoimmune disease I was diagnosed with in 2013.

My white blood cells began attacking my nerves and shutting down major muscle groups, my body turning against itself for reasons science still can’t fully explain.

The aggressive treatment designed to stop the disease’s march nearly killed me, causing a 105- degree fever that wouldn’t break, multiple blood clots and fears that my heart would sustain permanent damage even if I survived. Though there’s no test I can take to confirm it, the constant stress I was exposed to since I was a little boy could have led to a lifetime of inflammation that was changing my body’s internal wiring every day even though I didn’t know it, culminating in CIDP. I spent years of my childhood watching my father routinely beat my mother before watching my oldest brother be taken away to prison when I was a 9-year-old boy. Growing up, I lived in a tin can of a house – a green-and-white mobile home – in an underfunded school system that was still segregated four decades after Brown v. Board of Education. All the while, I was battling a severe stutter that was seemingly locked in when my brother plead guilty to first-degree murder.

Occasional stress can be healthy, teaching the body how to cope. Persistent stress puts the body in a near-constant state of emergency, making it difficult for the body to moderate itself, rendering people like me less capable of discerning the line between real and imagined threats. I was diagnosed with PTSD when I was a 34-year-old man. My therapist said my PTSD was linked to my childhood, meaning I went 25 years before getting help for it even as I battled daily ugly, violent images. The worst part, though, is knowing all of this — that “toxic stress” kills and ruins lives — but never being able to say it definitively, because the science isn’t that finely tuned yet. Racism kills. Literally.

When CIDP descended upon me, there were days I neither could walk nor had enough strength to fold a large towel. Since those dark days, I’ve made enormous progress. I’m in remission. I’m back to jogging 6 miles a day. I’m healthier than many people who never experienced anything like CIDP. But my body isn’t like it was before. Scars remain, as does CIDP. I can still feel the subtle disruptions and tinglings beneath my skin that were with me long before my diagnosis. They were signs I hardly paid attention to because they caused no immediate or detectable pain.

What CIDP did to me, white supremacy has done to the United States. Its causes are myriad, though largely mysterious and mystifying. The damage it leaves in its wake is often subtle, though pernicious. Sometimes its presence can’t be ignored when it announces itself in violent spasms. It’s why no discussion about white supremacy can be complete without examining the roles we all play, not just those played by Trump supporters or even avowed white supremacists. It’s not just about those carrying tiki torches or committing massacres in black churches or synagogues. White supremacy is embedded in this country’s DNA.

It’s not happenstance that there never has been racial equality in America, a country which coupled race-based chattel slavery with demands for liberty and justice. That makes the Black story unique in ways I wish it wasn’t. We don’t know what it feels like just to be American in a country that from the beginning hated and despised us for being black, and now hates and despises us for refusing to relinquish that blackness. And yet, here we are, still rising. Though they enslaved us, we didn’t give up. Though they lynched us, we didn’t give in. Though they kill us on video in broad daylight and hide behind shiny badges to absolve themselves of all responsibility, we refuse to back down.

I didn’t have to take the Adverse Childhood Experiences test or study trauma’s effects on the developing child’s brain, as I did at Harvard University for a year during a Nieman Fellowship, to know that truth. I can feel it in my bones. I can’t not feel it. I can hear it subtly coursing through my veins. It colors everything I think and feel. That’s the part of the American story many don’t want to hear, that we “overcomers” have wounds that won’t heal, that can only be managed, that we must reconcile ourselves to. That’s not a cry for help; it’s a scream for recognition, not for those of us who have trod the stony road, but for those still making their way up the rough side of the mountain.

This excerpt is taken from the new book “Why Didn’t We Riot?: A Black Man in Trumpland” (October 2020) by Issac J. Bailey, a Davidson College professor, Harvard Nieman Fellow, USC Center for Health Journalism National Fellow, and CNN.com and Marshall Project contributor.