Even in San Francisco, Heat Is Turning Deadly. That's Not Something Colleen Loughman Expected.

Molly is one of the recipients of the 2018 Impact Fund, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

How Hot Was It In California Homes Last Summer? Really Hot. Here's the Data

Investigation Finds Home Can Be the Most Dangerous Place in a Heat Wave

Extreme Heat Killed 14 People in the Bay Area Last Year. 11 Takeaways From Our Investigation

It's getting (dangerously) hot in Herre

Being outside can be dangerous, especially at school

What you need to know about LA’s urban heat problem

Sweltering in nursing home, 95-year-old succumbs to heat, as climate endangers most vulnerable

The danger of urban ‘heat islands’

New Rule Would Require Employers to Protect Indoor Workers From Heat Illness

Colleen Loughman with one of her two cats, when she was a student in the 1950s at Holy Names University in Oakland. Loughman died in September 2017 from the heat, a day after San Francisco hit a record 106 degrees. (Photo: Barbara McGovern)

Reporter Molly Peterson conducted a 5-month investigation into heat in California, in partnership with KQED Science. In a series of stories, we will examine who's vulnerable and why, and what it will take to protect people who are vulnerable to heat illness and death at home or on the job.

Last year, as a Labor Day heat wave descended, Claudia Hernandez was trying to pry open the windows of a house in San Francisco, from 400 miles away.

That weekend, San Francisco hit 106 degrees, an all-time record. After two straight days topping 100, Hernandez, who lives in Orange County, pleaded with her godmother, Colleen Loughman, to open her windows and let a breeze through.

Like most in the city, Loughman’s home lacked air conditioning. “A fan, an old school fan, that's all she had,” Hernandez said. “And her windows were like maybe one-eighth open.”

Talking with her 82-year-old godmother, Hernandez felt something was off.

“You could hear that she was, I don’t know, like, drained,” she says.

Colleen Loughman died the next day, in the house her parents had built. She was at risk because her aging body couldn’t acclimatize to intense, fast-arriving heat. She was vulnerable in her home, without a way to cool down. And though she was loved, she was isolated.

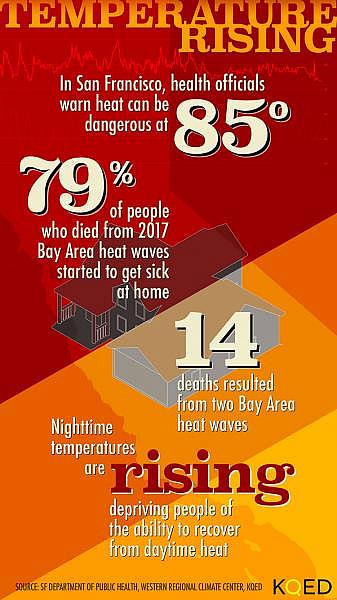

In June and September of 2017, two heat waves killed at least 14 people in the Bay Area, and sent hundreds more to the hospital.

San Francisco was caught off guard, says the city's deputy director of public health, Naveena Bobba.

“What we were seeing is really a huge health emergency,” she says.

The past five summers have been California’s hottest on record.

Even in cool, coastal parts of the state, heat, a sneaky and growing threat, is now one of the state’s top climate-related public health risks.

Why Older People Are At Risk

Last September, Loughman wanted her windows closed because she had been having lung trouble, and she feared smog and smoke would make it hard to breathe. She had heard air quality alerts on the news, issued by regional regulators.

Spiking heat worsens asthma and lung conditions and raises risks for older people in particular.

Older people have to work harder to stay cool, says Dr. David Eisenman, who directs the Center for Public Health and Disasters at UCLA.

“When your body normally gets hot, it cools down by transferring heat inside its core out to the skin.”

For most people, sweat cools the body well, but not for older ones. “They have a less effective ability to sweat,” he says.

Older bodies hold less water than younger ones, putting older people more at risk in a heat wave. And older people are less sensitive to becoming hot and thirsty.

Over several hot days, all of that means physiological heat can build up without relief.

And Colleen Loughman wasn't prepared for that in her foggy Parkside neighborhood.

Isolated in Her Own Neighborhood

St. Cecilia Church planted a Catholic community a century ago in a neighborhood set among sand dunes and eucalyptus trees: Parkside. Loughman grew up on 14th Avenue, and in Catholic schools: elementary at St. Cecilia’s, high school at St. Rose Academy, a masters degree in music at Holy Names University, across the bay.

But she never roamed too far from Parkside, where people were close knit, says her lifelong neighbor, Bob Schumann.

“I used to go to the house for birthday parties, and they were always playing the piano or something like that,” he says.

Hernandez noticed, and wondered whether her godmother needed more care and companionship.Her parents died; then a few years ago, her sister. Some of the old guard moved out, replaced by young, new transplants. Parkside was changing.

But a strong-willed Loughman wanted to stay put. "I’m okay," Hernandez says her godmother told her, "I’m okay by myself."

Heat Builds Up

Daily calls kept close a relationship that began 30 years ago between Loughman and Hernandez, as an accident of fate.

At the time, Hernandez was just 3 years old, arriving at a new foster home, belonging to Barbara McGovern in San Diego. Visiting McGovern was a longtime friend and former piano teacher of McGovern’s, Loughman.

“Colleen was so thrilled just to be around that child,” McGovern remembers. “She stayed for about two weeks.”

Loughman remained a San Franciscan, born and bred; Hernandez grew up, got married, had kids and settled in Orange County. She and her kids Ezekiel, now 15, and Natalie, 12, visited San Francisco every summer.

The daily call was usually newsy, an hour-long update: how’s your day going, how’s work, Ezekiel’s baseball, Natalie’s softball.

But when they quarreled about open windows that Saturday, heat soured the conversation.

This social media post by Claudia Hernandez shows her with her two children, Ezekial and Natalie, and godmother, Colleen Loughman. (Photo: Claudia Hernandez)

Don’t call me, Loughman said. I don’t want to talk. Loughman was stubborn, and Hernandez got the point: “She didn’t want to talk.”

But she called back the next day, Sunday afternoon, all the same.

No answer.

By 7:30, Hernandez was calling every 15 minutes.

Then every 10 minutes.

She finally reached a woman who ran Loughman’s errands. Please go over there, she said. Around the same time, Hernandez asked her husband, Jose. to call the San Francisco Police Department.

Jose told the dispatcher Loughman had not picked up her phone. “All right,” Police Dispatcher 236 told him, promising a welfare check. “We’ll get an officer out there as soon as possible.”

Last Sept. 3, Hernandez listened over the phone in agony as Loughman’s helper found her. She was unconscious. The helper tried to rouse Loughman: Colleen, Colleen.

That’s when paramedics arrived to help.

In a recorded emergency call, responders say that someone on scene is trying resuscitation. But Loughman was pronounced dead on scene, at 9:34 p.m.

'Actually, Everybody Is At Risk.'

Dangerous overheating isn’t something that happens only to elderly people.

In the temperate Bay Area, heat is a surprise we don’t quickly adjust to.

“It takes almost two weeks for your body to acclimate to the heat,” says SFDPH’s Bobba. "And given that heat kind of comes really quickly and leaves fairly quickly in San Francisco, our bodies don't acclimate.

People in the Bay Area are particularly vulnerable to heat illness even at lower temperatures, according to Rupa Basu, chief of the air and climate epidemiology section at the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. She points out that when heat spikes in the bay, the health effects are similar to what happens in hotter cities with hotter heat waves.

San Francisco’s 2017 Labor Day heat wave made headlines for two consecutive 100-degree daytime records. It was also warm at night - over 80 degrees near midnight both Friday and Saturday. During hours people would normally recover from daytime heat, it was hotter than days often are.

Scientists say overnight heat doesn't only happen during spiking temperatures; a changing climate is pushing up nighttime temperatures overall. That sneaky kind of a heat wave is becoming more common in California, observes UCLA climatologist Daniel Swain.

“The magnitude and frequency of heat waves that we're observing today would have been vanishingly unlikely in a climate without human influence,” he says.

Preventable Deaths

As climate changes heat risk, public health officials say warning systems are changing too.

But Bay Area conditions are complex: Counties here can experience wildly varying weather conditions at the same time; all decide slightly differently when to issue heat alerts.

Santa Clara County, which recorded five heat-related deaths last year, explicitly relies on the weather service in its heat emergency planning. So does San Francisco. After last Labor Day, the city has become more aggressive, according to SFDPH’s Bobba, initiating warnings when forecasts indicate daytime temperatures of 85 degrees or above.

Other counties are developing emergency response plans for heat. Contra Costa considers 96 degrees to be an extremely hot day in the eastern part of the county.

Excessive heat kills more Americans than any other disaster. But even in changing climate, heat-related deaths are preventable. Around the bay, public health officials and doctors, counties, cities and neighborhood groups are allied in rethinking how to find, warn and check on vulnerable people.

Colleen Loughman’s goddaughter is still haunted by her last words.

“She just said, ‘This heat is killing me. I can't talk right now. I don't want to talk.’” And that was it.

Last fall, after the heat broke, Claudia Hernandez learned she was pregnant. Her new daughter’s middle name is Coco, her nickname for Colleen. And she lets her own air conditioning bills get higher: Hernandez says she’s now determined not to let anyone she loves suffer in heat again.

Editor’s Note: Amel Ahmed was a contributing reporter on this story. This reporting is supported by a grant from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Impact Fund.

[This story was originally published by KQED Science.]