Nearly two years after ICE came to town, trauma still haunts these Iowa families

This story was completed as a project for the 2019 National Fellowship.

photo by Chris Walljasper/The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting

Editor’s note: This story was produced with support from the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship and by the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Luis bent over his front porch, one knee on a piece of plywood as he muscled an old hand saw through a cut in the wood on a warm day in early February. He was repairing a section of flooring in the small white house he shares with three other men on a quiet street in Mt. Pleasant, Iowa.

The cuts became more challenging as the saw caught in the wood. Luis, whose name has been changed for anonymity, shook his head and said he once owned newer power tools that would make the job much easier. But two years ago they were stolen while he was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

On May 9, 2018, Luis and 31 other workers from Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras were arrested during a federal immigration enforcement action at MPC Enterprises, a concrete plant on Mt. Pleasant’s west side. Some of the men who were detained were undocumented. Some had climbed their way from base laborer to middle management.

Unlike many of the men detained who have received work authorization while they await final immigration decisions, Luis, to this day, is still awaiting clearance to legally go back to work.

That state of limbo has left him idle for nearly two years, save for a few odd jobs he’s been able to pick up around town. He’s done yard work or painting, even cleaning manure out of hog confinements outside of town. The lack of consistent work has left him hungry at times.

“I feel like a zombie,” he said through an interpreter.

The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting conducted an eight-month review of health studies, government data and interviews with researchers, undocumented residents and community leaders on the aftermath of the 2018 raid in Mt. Pleasant, finding that families and the community remain traumatized by the events, long after the attention by national media and local support waned.

The raid at MPC enterprises is part of a trend of increasing worksite raids, according to a Midwest Center analysis of federal data and interviews with immigration officials.

Additionally the review also found:

- The number of administrative arrests of undocumented workers in worksite immigration raids increased more than 18 times between 2016 and 2019, from 169 to 2,048, according to an analysis of federal immigration data provided by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

- Undocumented workers are arrested at much higher rates than civil and criminal actions against their employers.

- Undocumented workers in the 2018 raid were detained for more than a week - some for nearly a month - leaving their families to struggle for food and expenses while scrambling to raise the full $10,000 bond.

- Nearly two years after the worksite enforcement action at MPC Enterprises, many of the men detained, as well as their families, struggle with mental and physical health issues related to trauma from the raid.

“They can’t do anything, in that moment,” said Ronald Carrillo, a small business owner in Mt. Pleasant who emigrated legally from Guatemala in 2001. “It’s devastating, like a hurricane devastates a town. But in this case, this hurricane devastated the Hispanic community.”

Mt. Pleasant local law enforcement declined to be interviewed for this story. Undocumented residents requested anonymity. They are identified in this story by pseudonyms and were interviewed through an interpreter.

Mike Moehle, the vice president of MPC Enterprises, said the company is still dealing with the issue and declined multiple interview requests.

Danielle Bennett, a spokesperson for Immigration and Customs Enforcement said the increase in worksite enforcement actions reflects priorities outlined by then acting Immigration and Customs Enforcement director Tom Homan.

Bennett said undocumented workers are not the primary target in worksite enforcement actions. But the raids are meant to have a chilling effect on illegal immigration, making undocumented workers think twice before coming to the United States illegally for work, she said.

“This does tie to border security,” said Bennet. “If you make it less likely that that work is available, it reduces one of the pull factors of crossing the border.”

She said, “the focus of worksite enforcement is on the criminal investigation and the pursuit of the employers. But at the same time, we’re not turning a blind eye to the illegal workforce.”

The raid may have been targeting the employers, but the fallout was felt by the workers.

The men who were caught up in the 2018 raid at MPC Enterprises were violating civil law, not criminal, said Rodrigo Reza, a volunteer for Iowa Welcomes Immigrant Neighbors, or IowaWINS, a community organization started by the First Presbyterian Church in Mt. Pleasant.

“Most of the people arrested, they were good people. The only crime was they didn’t have papers,” said Reza. “They were supporting their families. They were role models for the community.”

The raid

Carlos, who requested anonymity, was on break at MPC Enterprises when the raid began. He was in the factory’s dining room, when ICE agents descended on the facility and arrested him. He said he was held for 30 days in ICE’s Hardin County Detention Center in Eldora, Iowa, 175 miles northwest of Mt. Pleasant.

“I thought, ‘my time has come,’” he said. “I’m a good person. I’ve never been involved in any crime. I’ve never been a drunk or had a record with the police department.”

Across town, sirens blared and helicopters blades beat the air.

As husbands and fathers were taken away, family members cried, said Carrillo.

At Mt. Pleasant Middle School, Dina Saunders taught English Language Learning (ELL). She said the morning of the raid, her phone exploded with texts and emails.

“I went room to room looking for my students,” said Saunders in an email. “I did not know where all of their parents worked. When I found students, I called them into the hallway and told them that something has happened and they should call home to make sure everything is okay.”

That day, 32 men were taken to different county jails and ICE detention centers, some as far away as 300 miles away in Dodge County, Wisconsin.

Many of their families gathered at the home of a local community member.

Saunders and the middle school principal attended to provide support.

“Some women were really mad because they were not able to get documents to their husbands. The ICE officers didn't seem to care- they just rounded up anyone who fit the profile and didn't have papers on them at the time,” she said.

Saunders said many students weren’t in class the next day. But others had few alternatives.

“I remember one 7th grade boy who had three people in his family picked up by ICE in the raid,” she said. “He was at school because there was nothing else he could do. He was like a zombie, trying to make it through the day.”

Saunders said one student threw herself into her schoolwork as a way of coping with the chaos.

“It was the only normal thing for her,” she said. “The family was scrambling to get information and trying to figure out how to survive. The father was the sole breadwinner in the house.”

For Sofia, a mother of two from Honduras who also requested anonymity, the raid not only took her husband, but also her father and brother. Prior to the raid, her husband had reentered the U.S. after being deported. He was detained for a year after being arrested at MPC Enterprises, while he attempted to get legal status, but eventually was deported again.

Sofia said her brother and father, who had never been deported or received orders of removal, were held for five and three months, respectively, despite having no prior criminal history.

The uncertainty has weighed on both Sofia and her two sons, one 13-years-old, the other five. She especially sees it in her younger son.

“His anxiety has gotten worse. Any time he sees a man, he comes and hugs him, plays with him. He’s missing his dad. I just feel like he needs his dad,” she said.

For Sofia, the trauma has manifested as depression and anxiety.

“This thing got me to a point where I was depressed, badly. Clinically depressed. And so I was on medication,” she said. “I had to go to the hospital in Iowa City. I had a bad panic attack. I just couldn’t cope with this anymore. The pills are not working. I can’t sleep. The thought of ‘how am I going to cope?’ hangs around my mind, constantly. I really don’t know how I’m going to get through this.”

She said her sons keep her going.

“They’re the only thing. Because if I die because of this, or something bad happens to me, what’s going to happen to them? Who’s going to take care of them?” said Sofia. “The government is not going to take care of my kids. They don’t want any more economic burdens here for the country.”

She said she sees the irony, that her family, which once contributed to the community, now must rely on donations to the First Presbyterian Church to survive.

“The money barely pays the rent. And now they’re repossessing my car, because I have no way to pay. I’m in between a rock and a hard place - A very bad situation. No money coming, and there’s no hope he’ll ever come back here,” said Sofia. “He was the one that was supporting the family. I never had to apply for any kind of assistance.”

She said she fears applying for public assistance will jeopardize her status as well, as the Trump administration has implemented ‘public charge’ rules that states incoming immigrants must not be a burden on the country, or they may be turned away. The Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization, said the new rule has led to a chilling effect on immigrant families seeking aid.

“I’m just a resident, I’m not a citizen. So I think I’ll be affected, if I take public assistance,” said Sofia.

As the men sat in county jails across the Midwest, the families, with the help of community organizations like IowaWINS, League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the Eastern Iowa Community Bond Program, began searching for those who had been detained.

Luis said he was held in the same detention center as Carlos, in Eldora, Iowa, for three and a half weeks before being released on bond.

“I was feeling terrible. I am the only source of support for my family, especially my children,” he said.

When he was released, Luis said he attempted to apply for asylum. After filling out paperwork and submitting fingerprints, he said communication stopped.

“Every time I call them, they said my application has been submitted,” he said. “Most people from Guatemala have already received either a decision, or appointments, or papers. But not me.”

Neither Luis or Carlos have been given permission to work again.

Both have found under-the-table employment that barely makes ends meet. Financial and food assistance from the First Presbyterian Church helps, but donations have dramatically tapered off in the nearly two years since the raid.

“I come here, and get the essentials,” said Luis. “I save as much as I can for rainy days.”

Carlos is even further limited by his health. Around a year after the raid, he had a blood clot and spent three days in the Henry County Health Center in Mt. Pleasant.

“I’d never had health problems when I was working before,” he said.

Today, with his work permit in limbo, his entire case seems to have fallen off the map.

“They keep on changing and moving my court date. Now there is no court date. No news about a court date. Nothing official,” he said. He’s unsure what to do. “I want a work permit. But I don’t know.”

Sofia struggles to see a solution for her family.

“I don’t have any means to survive,” she said, picking up groceries from the First Presbyterian Church’s weekly food pantry. “I’m here for some essentials. But, you need cash to pay for utilities. So right now, I’m in a very desperate situation,” she said.

The trauma of detention

For those detained in the Mt. Pleasant raid, bond was set at $10,000, regardless of criminal history. In the criminal court system, a person can pay a bail bondsmen a fraction of the set bond to be released. But no such system exists for immigration court, so families scrambled to pull together the cash.

The men detained in Mt. Pleasant had court hearings in Federal Immigration Court, more than 250 miles away, in Omaha, Nebraska. But many court dates have been delayed for months and even years, due to backlogs. The court has 12,653 active pending cases, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

“The Nebraska court that sees most cases in Iowa has an average waiting time of 850 days right now,” said Nicole Novak, assistant research scientist at the University of Iowa who studies the community health impact of immigration enforcement.

The court is already scheduling cases for April 2023.

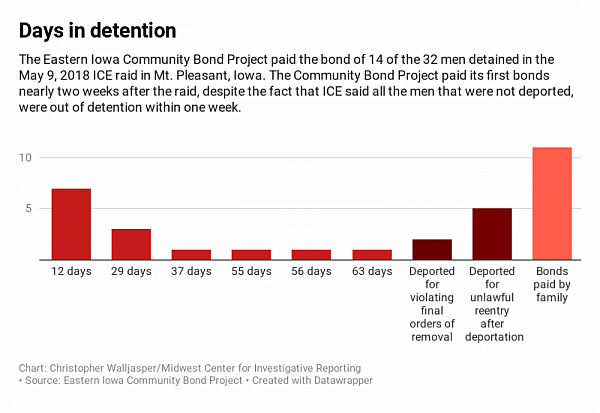

Shawn Neudauer, a spokesman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said most of the men who were detained were not in ICE custody for more than a week.

“Within a week, they were all out of custody,” he said.

He said five were prosecuted for “criminal reentry after lawful deportation.” Returning to the country after being deported is a felony. Neudauer said those men were transferred to the U.S. Marshals, to be held until their court cases. Two others had been given final orders of removal, but had not yet left the country. Neudauer said they were deported as soon as travel arrangements could be made.

Many workers and their spouses dispute Neudauer’s claim that most were released within a week.

“They lied to you. Flat out. It was three and a half weeks,” said Luis.

Julia Zalenski is the legal director and co-founder of the Eastern Iowa Community Bond Project, a non-profit that aids detained immigrants with bonds and legal services. She said, of the 14 men for which the organization posted bond, the earliest was 12 days after the raid.

“In cases where the families were able to pay themselves, it generally happened faster,” she said. “That obviously highlights the injustice of money bonds, in that they disproportionately harm poorer people.”

Chart: Christopher Walljasper/Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting; Source: Eastern Iowa Community Bond Project

For those who couldn’t afford the bond, court dates came more quickly.

But that, too, presented problems. Martha Wiley, a volunteer with IowaWINS said members of the First Presbyterian Church, who provided detainees with transportation, saw court hearings full of contradictions and abuses of power.

“The guy was supposed to be having his court case. His family was there. Our church representative was there. But the guy wasn’t there. Because ICE still had him in detention up in Eldora (Iowa). But the ICE attorney, the government attorney said to the judge, ‘He’s not here. Let’s just get this over with faster and deport him,’” said Wiley. “The judge was really ticked. That does not make any sense to most people. That wouldn’t fly if you were a U.S. citizen.”

Bennett said the handoff between ICE and the Department of Justice can cause challenges, but the agency tries to release workers not charged with criminal offenses as soon as possible.

“If they were non-criminal, most people will be arrested and released later that day. They’ll be given a notice to appear in immigration court,” she said. “ICE does not make the determination on who has authorization to remain in the United States. That’s up to the Immigration Court, or USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services).”

Neudauer said an immigration judge may have given some of the men the opportunity to leave the country voluntarily rather than face deportation proceedings. They then could apply for lawful entry, without a deportation counting against them. Others have been granted work permits while they await final determinations on their cases.

Trauma across the community

Novak said, as she has studied the community health impact of immigration enforcement, she has seen the broad impact of ICE raids in Iowa.

“It’s not just 50,000 immigrants who don’t have a status, and might fear arrest or deportation. It’s also the over 20,000 children in Iowa schools who have at least one undocumented parent,” she said. “Not to mention all the other people who work with these folks, live in their communities, go to church with them. This is something that ripples out and affects far more people than those who are arrested.”

“The people whose health is shaped by immigration enforcement is not just those targeted for arrest, but also people who are in their family, often people who are the same ethnicity,” Novak said.

In 2017, Novak published a study on the impact of a 2008 immigration raid in Postville, Iowa, on Latina mothers and babies.

“Infants born after that raid were more likely to have low birth weight, which is a risk factor for health problems later in life,” said Novak. “This is something we saw in the whole state, not just in the town of Postville. The whole state was fearful for several months after that event. We saw a change in the health of infants born afterwards.”

Wiley, who also serves on the Mt. Pleasant school board, said the school district has been trying to address adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which can cause long-lasting mental and physical health problems, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She sees multiple ways the raid has negatively impacted the lives of the children in her community.

“Having your dad scooped up and incarcerated, that would be an ACE (adverse childhood experience). Food insecurity is an ACE. Having to move at the drop of a hat, that’s another ACE,” she said. “They’re going to carry that for the rest of their lives. It’s going to be there. Hopefully they’ve found folks who are loving and supportive and playful and have linked arms with them at this church. At least they have that in their back pocket.”

Elizabeth Bernal, a founding member of the Eastern Iowa Community Bond Program, said she’s seen the mental and physical toll these detainments can have on children.

“The student’s going to school, and they’re thinking: ‘What is going to happen the next day? What’s going to happen when I’m done at school?’ So they don’t concentrate,” said Bernal. “They worry about too many other things — not only school. They worry about who’s going to take care of me? Who’s going to be responsible? They start to stress out, and the health issues start coming down. We see a lot of problems with the students,” said Bernal.

Carrillo has been in the U.S. nearly 20 years, but still feels the uncertainty rippling through the community. He sees it in his neighbors who struggle to put food on the table for their kids because of jobs lost and spouses deported. He sees that it could just as easily be his family facing those challenges.

“That is the struggle. I’m feeling free. But at the same time, I feel like I’m in jail, because who knows what will happen today or tomorrow,” said Carrillo.

Trust in local law enforcement among the immigrant community has also frayed. The Mt. Pleasant Police Department received little notice prior to the raid, but did cooperate, providing traffic control during the enforcement event.

Mt. Pleasant Chief of Police, Lyle Murray, declined to comment for this story.

Novak said these events make people hypervigilant, creating tension anytime they see something that reminds them of the enforcement action.

“A lot of people, including people directly impacted by the raid or just people who responded in the community, talked about getting really scared when they see white government vehicle vehicles on the highway,” she said.

Wiley said it’s made the men and their families nervous to engage with the larger community.

“Completely fearful,” said Wiley. “Anytime they saw police.”

She said before the raid, the families didn’t even utilize non-government charity, such as the local thrift shop.

“They keep low profiles, or they try to. They don’t even go to the Fellowship Cup - the Mt. Pleasant version of the Salvation Army. I had to draw maps. And still they didn’t go, because they were afraid they would be spotted,” she said.

Bennett acknowledges ICE worksite enforcement actions have an impact beyond the day of the raid and the business under investigation. But she said questions of whether or not the laws are fair were outside the purview of ICE.

“I understand. There’s a personal toll. But we have laws in this country and we enforce those laws,” she said. “Unfortunately, the consequence of people breaking the law is being arrested. There are human consequences to that.”

Reza said blaming the system ignores the human toll exacted by this method of immigration enforcement.

“The system needs to be fixed. But we need to think about the person next to us, and see how we can help,” said Reza.

Carrillo said he worries about the pressure facing the young Hispanic people in his community.

“We need to support our kids, that they can work, but they can continue their education, change their lives, change a different future,” he said.

Carrillo has seen that progress. His eldest daughter is 27, and will finish medical school and become a doctor in 2020.

Trey Hegar, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, said that’s the goal of the church and IowaWINS as well --- Moving beyond the immediate needs, to help those impacted by the raid improve their standing in the community.

“We’re looking 10 years out. How do we help people start businesses? If they’re getting permitted to work, and they don’t want to just be a laborer, some of them want to go to school,” he said. “We’re trying to help long term, not just in the next few weeks, but in the next years. And hopefully, 20 years from now, we’ll be telling the story about one of the kids who came here from Guatemala was a valedictorian.”

In the aftermath of the raid, Luis said he cried so much, feeling helpless.

But all that faded away when he spoke about his 14-year-old son, Manuel. He said he’s only seen his son in video calls back home. Luis left Ciudad Hidalgo, west of Mexico City in the Mexican state of Michoacán, when his wife was pregnant, to escape cartel violence that he believes would have killed him long ago. And now, his son is following the same path.

“As the boy grew, we became afraid that the cartels could recruit the boy,” he said. “If you don’t want to work for them, you’re dead.”

So at the beginning of the year, Manuel, along Luis’ older daughter and her husband, began the journey north to the U.S. border.

“My son went to El Paso and asked for asylum because of the cartels. He said, ‘Here I am. I am running away from violence. Please help me,’” said Luis, tears coming to his eyes.

Luis has been preparing the house, making repairs for his son’s arrival from El Paso, Texas. Manuel crossed the border on January 20, and is trying to be placed with his father in Mt. Pleasant.

Luis’ son offers him hope, even as his own immigration status is in limbo. He said it’s better than the constant fear of the cartel’s back in Hidalgo.

Manuel has been in detention in El Paso for nearly two months. Luis said he’s sent fingerprints and paperwork twice, but the process continues to drag on. He said he spoke to Manuel recently, who said he’s being treated well.

Yet the future in Mt. Pleasant, for both Luis and his son, is still uncertain.

Luis could be deported, leaving his son without family in a strange country. His son not only has to navigate the challenges of a new school, but do so while learning a new language in a politically charged environment that isn’t always favorable to immigrants. For Luis, it’s better than what he faced back home.

The journey, for both father and son, has been full of setbacks and hardships. But Luis said he’s excited to be able to provide a better life for his son.

“All I can tell you is, it was God’s will that I am here. Otherwise, I would have been dead already in Mexico.”

Special thanks to Franklin Ruiz and Maria Mellado, who provided interpreter services during interviews with undocumented workers and their families.

[This article was originally published by MidWest Center for Investigative Reporting and was co-published on Iowa Watch.]