Racial and ethnic disparities in child removals go unaddressed here

Perla Trevizo is a recipient of the University of Southern California Annenberg Center's Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being.

Other stories in this series include:

Part 1: Arizona Daily Star special investigation: Fixing our foster care crisis

Part 2: Despite state progress in Arizona, 'a lot of desperation, isolation'

Part 3: Hard work of reunification often entails rehab, intensive home services

Reporters reveal deep faults in Arizona’s swollen foster care system

Shared goals, collaboration are keys to family success

Moments of high anxiety for deported dad on custody quest

When a parent is deported, path to reunion starts with Pima County group

For migrants, cultural barriers, life’s shocks complicate welfare cases

Barreras culturales, obstáculo para el bienestar infantil entre inmigrantes

Se unen para derribar muros para padres deportados

La ansiedad de un padre deportado peleando por la custodia de sus hijos

Arizona no atiende la disparidad étnica en niños bajo cuidado temporal

Metas compartidas y colaboración son claves para que las familias tengan éxito

Lorenzo Gonzalez, head of the Healthy South Tucson Coalition, directs a trash cleanup on South Sixth Avenue, an area of concentrated poverty and home to many children of immigrant parents.

(Photo Credit: Mike Christy/Arizona Daily Star)

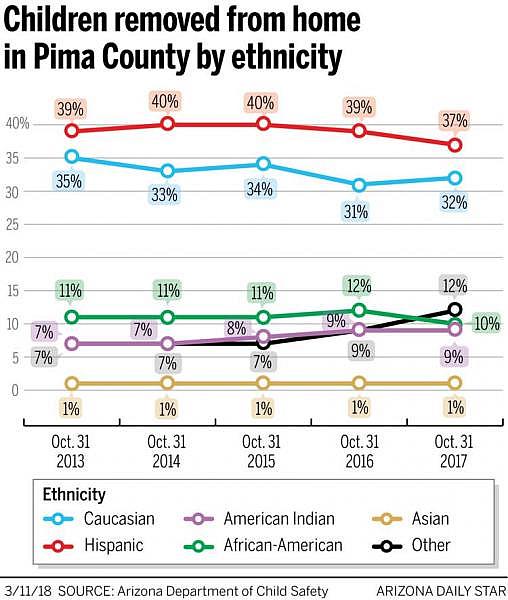

Arizona has one of the highest rates of children removed from their families in the nation, and more than 60 percent are children of color.

While that percentage mirrors the state’s overall population of children of color, there are disparities for two groups.

Black children represent 5 percent of kids in the state, yet they make up 15 percent of those removed from their homes because of possible abuse or neglect. Native American children make up 5 percent of Arizona kids, but 8 percent of those removed.

Hispanic and Anglo children each account for about a third of removals. Anglos constitute about 40 percent of Arizona’s child population and Hispanic children, 44 percent.

But while Hispanic kids may be underrepresented in the state’s child welfare system overall, national studies show that may vary by generation. A Texas study found that while first- and second-generation Hispanics were underrepresented, U.S.-born Latinos were overrepresented. Alan Dettlaff, dean at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work, also found in a separate study that, nationwide, 64 percent of Hispanic children involved in the child welfare system lived with a U.S.-born parent. In Arizona, 28 percent of children live in immigrant families, and 90 percent are U.S. citizens.

Another factor is that Arizona’s data may not be precise. The Department of Child Safety groups 6 percent of children removed from their homes into an “other” category for race or ethnicity. Caseworkers are supposed to ask families their ethnicity but advocates say at times they identify it by observation instead, which isn’t always correct.

Overall, children of color and those with immigrant parents have higher poverty rates and trail their white peers in educational attainment.

Many children of color are growing up in communities where unemployment and crime are higher; schools are poorer; access to transit and health care is more limited; and family supports and services are fewer, read the 2017 Race for Results report from the Annie E. Casey A foundation which focuses on children.

Those challenges put them a greater risk of maltreatment. For example, if parents work low-paying jobs with unpredictable hours and lack quality child care, that can lead to children taking care of children or being left home alone.

In addition to poverty, substance abuse, mental health issues and social isolation are all risk factors for child abuse and neglect.

De Jabbaj, center, plucks a bit of spearmint at the Garden Kitchen at 2205 S. Fourth Ave. The garden is part of an ongoing effort to boost food security in South Tucson. (Photo Credit: Mike Christy/Arizona Daily Star)

Pockets of poverty

The 85713 ZIP code, which includes South Tucson, has among the highest number of Department of Child Safety reports and removals in Pima County, with 607 reports and 132 removals in fiscal 2016.

South Tucson is a square-mile city of 5,600 people nestled inside Tucson city limits. More than 80 percent of its residents are Hispanic.

The average household income is less than $22,000, with nearly half of the population living below the poverty line. About 30 percent own their homes.

Unemployment is not as big a challenge as finding jobs that pay a living wage, “which means families need two to three jobs just to make it and (have) no benefits,” said Alonzo Morado, community engagement coordinator for the Primavera Foundation, which has worked in the area for decades.

There are many mixed-status families, which usually means a U.S.-citizen child is living with a parent not legally in the country. While immigrant families and other minorities struggle with the same issues as the community at large, getting help can be especially challenging.

Alonzo Morado (Photo Credit: Mike Christy/Arizona Daily Star)

Since the Trump administration promised to crack down on immigration through increased deportations and orders such as its travel ban, there’s been a rise in fear among immigrants here legally or not. Those without status fear getting deported and those with status are afraid to lose it.

“It’s really stressful. Families are scared to leave their homes,” said Kate Meyer, Community Prevention Coalition Coordinator at PPEP (Portable, Practical, Educational Preparation), an organization that provides education, training and practical life skills. They have a hard time reaching out for help, afraid they may say something wrong and authorities will come take them away, she said.

This can also leave immigrants hesitant to report child abuse, Dettlaff said.

On the other hand, he said, the strengths within many immigrant families — including two-parent households, extended family support and lower rates of drug abuse — may serve as buffers against those risks.

South Tucson is just one local example of concentrated poverty. More than 1 in 4 children in Pima County live below the poverty level.

But South Tucson is also a place where service providers and stakeholders came together to try to change its course. Healthy South Tucson is a multi-sector coalition whose members meet monthly to go over challenges and issues they see in the community.

(Credit: Chiara Bautista/Arizona Daily Star)

They hold a coat and shoe drive, and organize health clinics and neighborhood cleanups. They partner with groups like the University of Arizona’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Garden Kitchen to offer seed-to-table gardening and cooking education, aiming to boost food security and improve health.

“The overarching goal is to bring health to South Tucson across all community aspects. We want to touch on education, the environment, policy changes, health and nutrition — to get to the root causes of what really affects the community,” said Lorenzo Gonzalez, president of Healthy South Tucson.

The mission includes raising South Tucson’s home-ownership rate to 50 percent, Morado said. Primavera buys land and renovates homes to sell to low-income families as part of its home-ownership and neighborhood-revitalization project.

The group also wants to encourage the development of small businesses through micro-loans and access to commercial kitchens. “For every $1 spent in these businesses, it returns to the community six times,” Morado said.

“The one thing I’ve learned from working in South Tucson,” said Gonzalez, “is that everything in the community is connected.”

Years of talk, but little action

Disparities impacting children of color and immigrants in Arizona are not new.

In 2008, the Children’s Action Alliance produced a report on racial disproportionality in the child welfare system in Maricopa County. It said black and Native American children were more than three times as likely as white or Latino children in the county to be in foster care. It challenged the role cultural factors played in influencing decision-making; the availability of community support; and systemic or institutional factors coming into play, among other issues. The authors hoped the data would spur conversations and action.

A 2011 University of Arizona study asked whether parents who are undocumented immigrants are more likely than native-born parents to have problems with abuse, neglect, abandonment, substance abuse, poverty, domestic violence and mental health. Among those responding were 26 CPS workers, nearly all of whom “thought undocumented parents would be more likely to have problems with poverty, more than half thought they would be more likely to have problems with domestic violence and roughly one quarter thought they would be more likely to have problems with child neglect, abandonment, substance abuse, and mental health,” the study said.

Around the same time, a group of faith organizations formed to address issues of disproportionality, but it disintegrated when 6,000 reports of child abuse and neglect were found labeled “not investigated” by Child Protective Services amidst a growing backlog in 2013, said Roy Dawson, executive director of the Phoenix-based Arizona Center for African American Resources and member of that coalition.

Also, a 2012 report by the state’s child welfare agency mentions subcommittees in Pima County Juvenile Court that explored trends and factors associated with African-Americans, who were aging out of care at a higher rate; American Indians who were reunified at a lower rate and tended to be younger than children of other races in out-of-home care; and with refugee children. But priorities shifted. Today, Tina Mattison, the Juvenile Court’s deputy administrator, couldn’t find any reports about what, if anything, came of the subcommittees’ work. She wasn’t with the court in 2012.

The court also couldn’t provide the Star with breakdowns by ethnicity, race or ZIP code of court data about dependency cases — court cases that involve suspected child abuse or neglect.

No current initiatives in Pima County or Arizona address disparities and disproportionality in child-welfare systems —which also struggle to reflect the populations they serve. DCS did not respond to repeated interview requests from the Star to discuss the issue.

“I’m not talking about the hearts of people, but the heads of people,” Dawson said. “Most want to do the right thing but don’t know how. We need to create a pathway for them to connect with the right people.”

When racial biases are addressed, communities are empowered and there’s a commitment from within the system to address issues of equity, Dawson said, “there’s a much better chance of creating change.”

[This story was originally published by Arizona Daily Star.]