Road to recovering: Survivors of 9/11, Oklahoma City terror attacks share their stories

This story is part of a series on Dec. 2, 2015, terrorist attack survivors’ recovery and California’s workers’ compensation system. The project was undertaken for the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

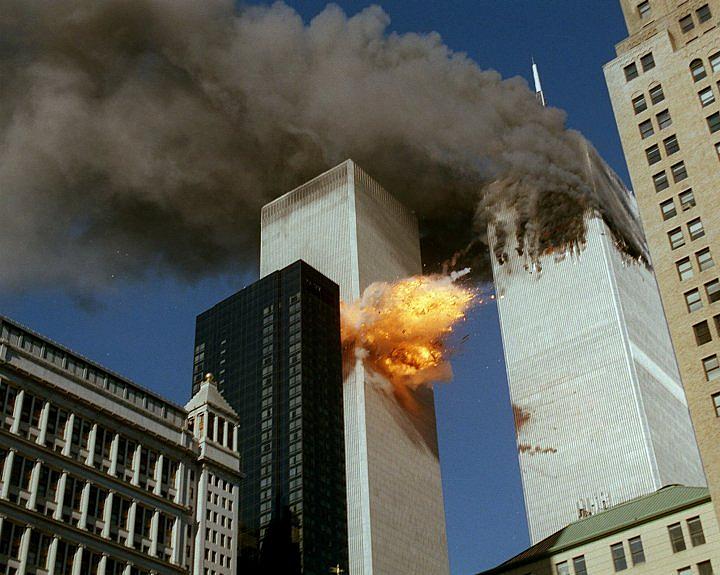

FILE – In this Sept. 11, 2001 file photo, United Airlines Flight 175 collides into the south tower of the World Trade Center in New York as smoke billows from the north tower. (AP Photo/Chao Soi Cheong)

Editor’s Note: Survivors of the Dec. 2, 2015, terrorist attack in San Bernardino aren’t the only ones afflicted with post-traumatic stress. Survivors of other terrorist attacks here and abroad also suffer from PTSD. Here, survivors of three attacks share their stories and how they coped.

Sept. 11, 2001

A blue-sky day can take him right back. When it’s 70 degrees, with no trace of a cloud overhead, Brian Branco is back in New York on Sept. 11, 2001. Back in the World Trade Center’s south tower, taking an express elevator to the ground after feeling a vibration and seeing papers fly outside his 78th-floor office window. He and Steven Weinberg wanted to go down to see what was happening, but his friend turned back to get something before reaching the elevator.

The elevator’s crammed with 50 to 60 loud, nervous people whose fear turns into hysteria when the elevator slows near the ground.

“They’re going back up! They’re going back up!” they scream, until the elevator doors opened and let them out.

FILE – In this Sept. 11, 2001 file photo, firefighters work beneath the destroyed mullions, the vertical struts which once faced the soaring outer walls of the World Trade Center towers, after a terrorist attack on the twin towers in New York. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

Brian and the others exit through the shopping mall. A block away, he turns a corner and sees a plane coming at him. He runs into another building as he feels the Boeing 767 slam into the south tower. The wings hit from the 74th to 84th floors. But the fuselage, the guts of the plane, strike floors 77 and 78 with full impact. Steven is on the phone with his wife when the plane hits.

“He didn’t get out,” Brian said.

The New Jersey IT consultant was left with post-traumatic stress disorder and survivor’s guilt.

“A lot of it,” he said firmly. “Survivor’s guilt will kill you if you let it.”

For the first few years afterward, if he left for work on a warm, sunny morning, he’d relive 9/11 in his mind through flashbacks the rest of the day. He’d feel anxiety and guilt. If he was headed to New York, he’d be hypervigilant, worrying what would come next.

Two years later, when he couldn’t stop asking why Steven didn’t leave, Brian got therapy and was diagnosed with PTSD. He went for four months but ultimately says what helped him was his wife’s encouragement to talk and willingness to listen.

“She would be like, ‘Talk to me, honey,’ ” Brian said. “I would say, ‘How many times can I tell you the same story over again?’ She would say, ‘However many times you need to.’ ”

His PTSD symptoms were constant for about five years, Brian said, because of 9/11’s scale, PTSD’s complexity and living so close to New York, where the attack’s aftermath became part of daily life. Even 16 years later, weather can trigger a flashback. Only now, he can control it.

A few months ago, a new therapist diagnosed him with anxiety but not full-blown PTSD, partly because he doesn’t avoid the attack site or avoid discussing that day. Avoidance is a major PTSD symptom.

He’s talked to survivors of 9/11 and other attacks through the World Trade Center Survivors Network and other survivor groups. He and wife, Cynthia, lead tours at the Ground Zero site and donate time at the National September 11th Memorial and Museum. Brian recovered by sharing his experiences with others.

“And that’s why, to this day, we volunteer down there as much as we do. Because it helps me to talk about it.”

Jerusalem bus attack

Fourteen years later, she still has trouble sleeping. Three to four hours a night is what she usually gets. There are no nightmares. No flashbacks. She just wakes up.

She was sitting next to a window on her way to meet a friend for dinner in Jerusalem when the bus exploded. Sarri Singer can still remember the shockwave that ripped through the bus June 11, 2003, when a Palestinian teen wearing explosives and shrapnel hidden under an orthodox Jew’s clothing blew himself up when they got to Davidka Square.

Relatives of Bat-El Ohana carry her coffin during her funeral in the cemetery of Kiryat Atta, near the northern city of Haifa, Israel, Thursday, June 12, 2003. Ohana, 21, was one of 16 people killed in Wednesday, June 11’s bus bombing in Jerusalem. (AP Photo/ Baz Ratner)

The terrorist had been two people away. Sarri never saw him. There was a ceasefire on. She wasn’t even watching for anything suspicious as they rode through downtown Jerusalem.

The explosion pinned Sarri against her seat. Shrapnel embedded in her mouth and tore through her shoulder, breaking her collarbone. Pieces of the bus hit her legs, her eardrums burst and her hair and face were burned.

Sixteen people, including everyone around her, were killed. One other person died later. Able to open only one eye after the blast, Sarri saw the man in front of her wasn’t moving. She screamed, but heard nothing.

After undergoing surgery to clean and close her wounds, the 30-year-old spent nearly two weeks in the hospital and returned to the United States.

Sarri didn’t have any PTSD symptoms until six months later. She and doctors think she initially pushed her trauma aside to speak out about the attack and terrorism in Israel.

Sarri, the daughter of New Jersey state Sen. Bob Singer, now believes there’s no common timeline for recovering from such trauma.

“I think PTSD can happen at any time. Anything can trigger it,” she said. “Someone could be fine one day and then something triggers it days, months or years later.”

She found what helps one person might not help someone else. Acupuncture lowered her anxiety and stress. But processing memories using a therapy called eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, didn’t work for her.

She found other American survivors of terrorist attacks in Israel because she needed someone to connect with.

Psychological counseling also helped her. Attack survivors are often isolated after trauma. Many won’t go for individual therapy, or go but it doesn’t help, said Sarri, now director of career services for Touro College in Manhattan.

In 2012, she started the nonprofit group Strength to Strength in New York to bring attack survivors together. The group gives free long-term support to survivors, their families and victims’ relatives through retreats and social events, speakers’ programs, self-defense classes, one-on-one connections and expert trauma help.

Sarri thinks peer-to-peer support helps terrorist attack survivors recover better than psychotherapy.

“When we share, we become connected. And then we don’t feel alone in what we’re going through,” she said.

Oklahoma City

Nightmares always follow the smell of smoke. Wherever the smoke comes from, Dorothy “Dot” Hill will dream that night of Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995.

The way her body swelled when the rental truck exploded outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building as she sat in a break room at 9:02 a.m. Trying to get back to her first-floor General Services Administration office. Her growing fear for the daycare kids as she escaped through an exit and found cars burning in the street.

The north side of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City is shown missing after a truck bomb explosion, in this Wednesday, April 19, 1995, file photo. (AP Photo/File)

“That’s when I saw the front of the building was gone. I thought it was like a war zone in Bosnia,” she said.

In her nightmares, Dot is still trying to get people out. She’s helping coworkers onto body boards so they can be loaded into ambulances. She’s climbing to the man sitting on an upper floor whose eyes plead for help until someone tells her he’s already dead.

Two coworkers were killed. The children who died had been in her building – most in the daycare her toddler grandson had attended until four months earlier.

“I knew a lot of those babies,” she said.

There weren’t many treatment options for PTSD in 1995. Dot was put out twice on one-year medical leaves – six months after the attack and three or four years later.

Talking with a counselor and other Oklahoma City bombing survivors, including coworkers, have helped her heal.

“Ignoring it definitely does not help,” she said.

Oklahoma resident Dorothy “Dot” Hill survived the attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995.(Courtesy photo)

Counseling can help survivors understand what triggers them and sets off PTSD symptoms or recognize they’re more stressed and sensitive at certain times. Talking to someone who understands is key. Friends and family might not get it, she said.

She still suffers from survivor’s guilt and PTSD. Loud noises leave her shaking. She throws up every day she works at the federal courthouse downtown but can’t afford another medical leave.

Dot said her religious faith gave her courage to get help. Once she felt she’d worked through enough trauma in two years of counseling, she began reaching out to other terrorist attack survivors through the newly formed Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism and now as president of Oklahoma City Bombing Outreach.

Helping others, especially 9-11 survivors, stirred things up but ultimately helped by expanding her focus and inspiring her to deal with trauma differently.

“By the time 9-11 happened, I was definitely in a stronger place,” she said. “I knew these people needed me to be strong.”

PTSD recovery tips shared by terrorist attack survivors

- Don’t blame yourself for the terrorist attack or beat yourself up for anything that happened.

- Don’t think that you did something wrong because you lived and someone else didn’t.

- Recovery takes time and can’t be rushed. It’s OK to get what you need to heal. Focus on taking care of yourself.

- Don’t isolate yourself, because that can make things worse.

- There’s no consistency or common timeline for the aftermath of trauma, or the recovery and healing process. Everyone’s post-traumatic stress is different.

- Recovery is a constant process. Survivors can be fine one day, yet can still experience PTSD symptoms days, months or years after the original trauma.

- Talk to other survivors, including those who survived earlier attacks because they’ve recovered longer and have different views.

- If you can’t yet talk with other survivors, it helps just to be in the same room with people who’ve gone through a terrorist attack.

- Talking to someone who understands is key. Friends and family might not get it. Sometimes the best support comes from other survivors or victims’ relatives.

- Ignoring the traumatic event or PTSD symptoms doesn’t help. Counseling can help to understand what sets off PTSD symptoms.

- Helping others may expand your focus to include more than your traumatic memories and recovery efforts.

- Appreciate life. Don’t take things for granted, because you don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow.

[This story was originally published by The Sun.]