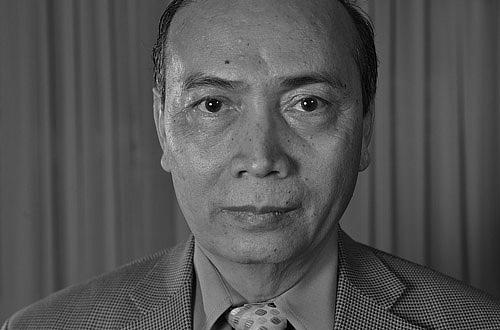

Sam Keo: Soul-searching helps win battle in mind

Sam Keo's battle with post-traumatic stress disorder began in his Long Beach home, where he would be visited by his late mother and dead baby brother. Now Keo, a licensed clinical psychologist with the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health, is able to discuss his struggles. But it took years of therapy, medication and soul-searching.

This article is part of a six-part series that looks at the effects of PTSD on members of the Cambodian community:

Part 2: PTSD from Cambodia's Killing fields affects kids who were never there

Part 3: At 92, she's still haunted by Khmer Rouge atrocities in Cambodia

Part 4: SAM KEO: Soul-searching helps win battle in mind

Part 5: ROTH PRUM: Genocide's horrors still haunt dreams

Part 6: ARUN VA: Narrow escape from becoming a killer

LONG BEACH - Day or night Sam Keo would be visited by his late mother and dead baby brother. He would stare into her reproachful eyes, see the baby's wasted corpse. And he'd hear her words.

"If you had given him your portion, he would still be alive," she said.

Problem is, it was more than 15 years since Keo's brother had died at the age of 3 from malnutrition and eight years since his mom had died of ovarian cancer. And yet there they were in Keo's Long Beach home, the mother's reproach as bitter and harsh and real as the day she first uttered it.

That is how Keo's battle with post-traumatic stress disorder started. Now Keo, a licensed clinical psychologist with the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health, is able to discuss his struggles. But it took years of therapy, medication and soul-searching.

"I couldn't close my eyes without seeing the Khmer Rouge," Keo says.

One night he recalls fighting back in his dream and socked his wife in the eye.

And then there was the memory of Aren, his brother. Keo and his family lived on a commune under the Khmer Rouge. All were on near-starvation diets with only a small bowl of gruel and rice per day to sustain them. Keo's little brother was sick and dying and his mother begged Keo one day to give the baby some of his food. Keo said he was sick too and needed the food to work. When Keo came back from the fields that day, his brother was dead and his mother blamed him.

Keo kept those memories at bay when he moved to the United States and was kept busy working, going to school and studying for his doctorate.

In 1992, I went to Cambodia. I was doing fine," says Keo, who was seeing his family for the first time in 10 years. "I went there seeking closure. I was looking for graves (of my family) and I couldn't find many. When I came back I was so distraught."

In seeking closure, Keo opened the gates to a nightmare.

Shortly after he returned to the U.S., the dreams began.

As a mental health professional, Keo knew he was not to blame, but that didn't lessen the shame.

"I didn't want to seem weak," Keo says. "I was supposed to be one of the better ones."

Twice Keo says he attempted suicide. But eventually he found a therapist he trusted and began taking the long road to recovery.

Had he not sought therapy, Keo says, "I probably would have committed suicide."

Part of the soul-searching and therapy can be found in a memoir Keo wrote titled "Out of the Dark, Into the Garden of Hope," released in December. It took Keo 17 years to write the book and was a journey that at times brought him to terrible depths.

"Sometimes I would write a paragraph and it would all come back," he says.

However, Keo says it was important for him to write the book to help others and to make sure his children understand his story.

"I had a duty to write this book," Keo says.