Trump plans to halt immigration, California growers aren't thrilled

This story was produced as a project for the 2020 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Ag workers exempted from COVID-19 shelter in place mandate, advocates fear for health

Protected in the fields but not at home: Salinas H-2A farmworkers at risk

‘The perfect storm of vulnerability’: Protection in the fields doesn’t follow farmworkers home

Monterey County ag workers comprise nearly a quarter of county COVID-19 diagnoses

Sixth person dies from COVID-19, Alisal and North Salinas hardest-hit in county

Monterey County growers face 'unprecedented losses' amid pandemic

Close quarters: Overcrowding fuels spread of COVID-19 among essential and service workers

Evicted Monterey County renters face greater risk of contracting COVID-19

Do California ag counties hold solutions to Monterey County farmworker housing crisis?

Monterey County advocates, growers urge renewed focus on farmworker housing

Housing bills aim to extend tenant, landlord protections for Californians amid pandemic

The Trump administration is considering cutting the pay of guest visa farmworkers during the coronavirus pandemic to help the farm industry.

President Trump tweeted late Monday that he planned to temporarily suspend immigration to the U.S. The president cited the need to protect jobs in light of “the attack from the Invisible Enemy,” a reference to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

"In light of the attack from the Invisible Enemy, as well as the need to protect the jobs of our GREAT American Citizens, I will be signing an executive order to temporarily suspend immigration into the United States!” Trump tweeted.

And California growers aren’t thrilled: They say it won’t help them much with their financial crisis. And they worry that it might even hurt them by creating uncertainty for their essential employees, prompting them to look elsewhere for work once the pandemic ends.

Unions and other worker advocates also worry that reducing farmworkers’ wages would cause hardships for people already living on the edge of poverty, and may end up lowering the pay of domestic farmworkers, too.

Hugo Marcos has an H-2A visa, which allows growers to temporarily employ guest workers from other countries if there is a shortage of workers willing to take the jobs. He spends his days cutting hearts of romaine lettuce for Foothill Packing, Inc., and returns around 6 p.m. to the Salinas motel where he will stay for months.

Marcos just arrived in Salinas, but this is his fourth year working U.S. fields on an H-2A visa. He has earned enough to build a two-bedroom home in the Mexican state of Michoacan, and take care of his wife and two children.

“Trabajar de campo es complicado y especializado,” he said. In English, that translates to “farmwork is complicated and specialized.”

It took Marcos a long time to learn the skills he has now: cutting the lettuce in a perfectly flat swipe to maintain a uniform look and size; removing excess leaves and handing the heart off to be packaged right there in the field.

More than 257,000 people worked in the U.S. on an H-2A visa in 2017. These workers have been deemed essential during the coronavirus pandemic by county, state and federal government regulations.

In California, H-2A workers earn $14.77 an hour this year, or about $118.16 for an eight-hour day, one of the highest in the country for these workers. The average wage of an H-2A farmworker, known as the “adverse effect wage rate,” or AEWR, is based on a survey of growers and farm labor contractors, and the AEWR varies state to state.

For the same labor in Mexico, Marcos said, he would earn 70 pesos an hour, something like $23.28 a day. A drop in pay would reduce his children’s quality of life, he said. “Reduciría en nivel de vida que les damos,” he said.

Yet the Trump administration’s Department of Agriculture is exploring cutting H-2A worker pay, according to an NPR report. NPR found that “new White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows is working with Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue to see how to reduce wage rates for foreign guest workers on American farms.”

The USDA declined comment on whether it is considering such a change, or how it would be accomplished. The administration could announce a temporary rule change, order a new rulemaking or issue an executive order.

“During these difficult times, President Trump and Secretary Perdue are doing everything to ensure farmers have the tools to carry out the vital work of feeding the American people,” a USDA spokesman told USA Today Network.

By cutting worker pay, the administration hopes to keep farmers afloat through the pandemic.

Without the wage cut, researchers expect to see up to a $688.7 million decline in sales leading to a payroll decline of up to $103.3 million between March and May of 2020.

The pandemic has shut down restaurants, schools, cafes and other regular buyers of wholesale goods, leaving farmers hauling larger loads to food banks when they can afford to, and letting food rot in fields when they can’t.

As the administration contemplates cutting pay to workers on the frontlines, farmers also may be on the verge of receiving a $16 billion bailout to keep their operations going.

But agricultural industry representatives and workers’ advocates alike say the move to cut worker pay won’t solve the food-supply-chain crisis.

“To see wages being depressed would be reason for concern and evaluation,” said Chris Valadez, president of the Grower-Shipper Association of Central California, which represents more than 300 companies. “We are one of the few industries still essential, still open for business.

“Longer term, it should cause us to reevaluate the AEWR system and what goes into it, but right now, I just think it would create more uncertainty in the mind of the employees,” Valadez said.

Union officials say a pay cut for temporary workers may reduce the pay of domestic workers, too, because the H-2A pay rate is considered the average pay for all farmworkers.

“To reduce their wages at any time would be of deep concern, given that many farmworkers are struggling to feed their own families,” said Gieve Kashkooli, the political and legislative director with the United Farm Workers, a union that serves domestic and foreign farm laborers. “It would be an even deeper concern to do that during this COVID crisis while the federal government has declared farmworkers essential. And it’s a total insult to them.”

According to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a nonpartisan think tank, H-2A workers are already underpaid compared to other workers.

“In 2019, the average wage of all nonsupervisory farmworkers was $13.99 per hour, according to USDA, while the average wage for all workers in 2019 was $26.53 per hour, meaning the farmworker wage was just 53% of the average for all workers,” read an EPI post. “And the average wage for production and nonsupervisory nonfarm workers—the most logical cohort for workers outside of agriculture to compare with farmworkers—was $23.51.

“In other words, farmworkers earned 60%—just three-fifths—of what production and nonsupervisory workers outside of agriculture earned.”

Anne Lopez, director of the Center for Farmworker Families, called it “un-American” to consider cutting wages during a health and economic crisis.

“They’re already impoverished,” said Lopez. “They live on the edge of survival, they have no guarantees. Right now they’re going through one of the worst periods I've ever seen...and to make things worse for them by cutting their pay? It’s obvious our president doesn’t consider these people as human beings.

“I think a lot of it’s racist, it’s classist, it’s to keep them where they’re at so they can’t progress. That’s why I say it’s un-American.”

Casey Creamer, president of the California Citrus Mutual, which represents 2,500 family citrus growers, said that although he had not seen a proposal from either the USDA or the Trump administration to cut H-2A wages, his group does not support cutting salaries of pickers.

“It’s not a political reality, it’s not supportive of our employees that we have in place. It’s just not a thing that we do,” he said.

‘Not the most significant tool’

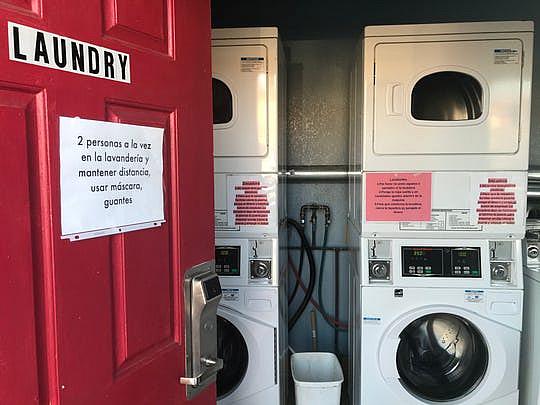

A sign on the laundry room door cautions motel H-2A guests that only two can occupy the room at a time. April 13, 2020. (Photo: Kate Cimini / The Salinas Californian)

Some industry representatives say the move to cut wages is detracting from the ultimate problem: a sudden drop in demand.

In the Ventura-Santa Barbara area, citrus growers are leaving lemons on trees, Creamer said. Unlike other produce, which can be disked straight back into the ground and used to fertilize the soil, citrus must be harvested or it will endanger next years’ crop.

“We can hold for a little bit longer and hope that restaurants open back up,” said Creamer. “Growers will have to pay to come back in and harvest to drop food back to the ground. We’re buying some time right now but it can’t go on much longer.”

Valadez said that if the administration wants to help growers, it should “put enough money in the system so employers can pay workers.”

“I know if the food service market is down, it’s down, and there’s nothing we can magically do to change that,” he said. “However, where federal stimulus is focusing on direct payments, we also need to focus on purchasing power to get that food into the hands of people that need it.

“Lowering the AEWR is a tool but I don’t think it’s the most significant tool right now,” he said.

Valadez suggested an injection of funds into purchasers still buying food, particularly ones seeing a real upswing in customers, such as food banks.

Hunger is a problem across California, and Monterey County has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the state. A 2016 report by the Monterey County Health Department placed the percentage of food-insecure people in the county at 34%.

At the Monterey County Food Bank, which typically serves 20% of the county’s adult population and 25% of its children, the number of people standing in line at the food bank has basically doubled, said the nonprofit’s executive director, Melissa Kendrick.

Many of those who take advantage of food banks are farmworkers themselves.

A food crisis

Some industry experts say without significant intervention, the farming landscape will be forever changed.

“We’re in a different world right now,” said Valadez. “As we move forward we might see a lower demand. That is extremely impactful to the industry and to the backbone of the industry: the workers.”

“Does going back to AEWR save the day?” asked Valadez. “I don’t know. Before COVID, I probably had an interesting quip to give you, but during this crisis I think there are other things that are more in-demand in the moment. Businesses need buyers for their product.

“We have to keep the system moving. Afterwards, we can have our debates and our cuts. But we have to keep the system moving.”

Some H-2A workers said they would still participate in the program even if wages went down, as they would make far more in the U.S. program than they would doing the same work in Mexico. Still, they said, it would be a blow to their finances and their plans.

Marcos has worked cutting romaine hearts for two years for Salinas-based Taylor Farms and two for Castroville-based Ocean Mist.

As Marcos washed up for dinner at a plastic washstand in the motel parking lot, pumping the water in bursts with his foot and lathering up with industrial green handsoap, he talked about his sons, the oldest, 8 years old, named for him.

They’re getting older, he said in Spanish, and he and his wife want to add a bedroom onto their blue-and-white home in Mexico so they could have their own rooms.

If his salary were to drop, Marcos said, it would hit his family hard. They would have to put construction plans on hold, probably for years.

“Suerte, pues, gracias a dios nos da la oportunidad venir por acá y lo aprovechamos después,” said Marcos.

“It was luck. Thank God I had the opportunity to come here. I made the most of it.”

[This article was originally published by The Californian.]