With HIV, the data isn’t as reliable as you think it is

In 2015, publications such as The New York Times touted the San Francisco “miracle” of dramatically reducing new HIV infections. Indeed, the city and county (they are one and the same) saw new infections fall 34 percent between 2012 and 2014. After living there for over a decade, I know that San Francisco is uniquely situated when it comes to HIV and AIDS — in terms of funding, political will, education, and empowered stakeholders. But I wondered how other counties in California were fairing in their prevention efforts, both social and biomedical, and whether San Francisco’s model could be imported to other locales to produce similar results.

I’m a senior editor for Plus magazine, the country’s largest publication for people living with HIV as well as those who care for them. Although 80 percent of our readers already have HIV, they are also concerned with stopping the spread of the epidemic, the availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and campaigns dedicated to functionally “ending AIDS” or, according to California’s slogan, “Getting to Zero” by 2020. We also understood that this topic would be interesting to the policymakers, doctors, and activists involved in reducing HIV infections in their own areas.

California, as a whole, is a wealthy state, with progressive social leanings, less fervent religious beliefs, and an interest in improving the health of its residents by policies such as expanding Medicaid access. These elements means that California faces fewer hurdles in reducing new HIV infections than many other states in the union.

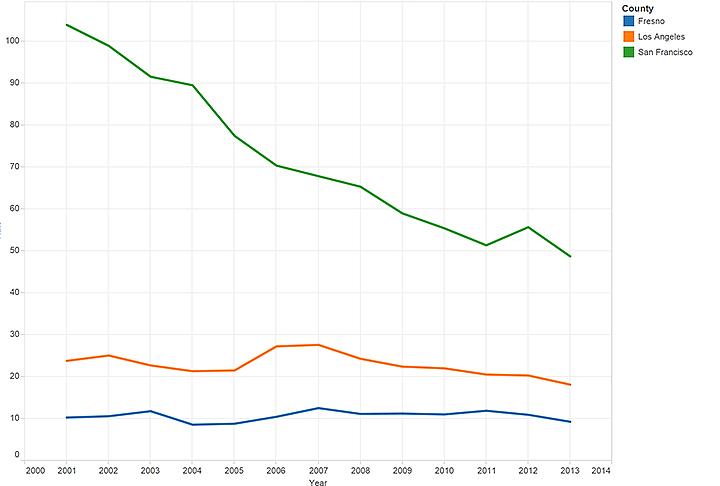

HIV Rates in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Fresno (per 10,000 people)

I decided to focus on three counties: San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Fresno. Each county has very different stats in terms of size, demographics, whether its urban or rural, and available resources. These differences rendered my ability to make comparisons far more difficult than I initially anticipated, in part because they dramatically impacted the quantity and quality of data available from each county.

While every county collects data on people living with sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, few jurisdictions are employing their data collection quite the way San Francisco is. San Francisco County, for example, employs a slew of epidemiologists and statisticians to monitor and interpret the results of their HIV surveillance and apply that information to their prevention efforts.

Interpret the data with caution

One of the first things I decided to do in researching this story was to dive in deep and really understand San Francisco’s HIV surveillance data and try to figure out, to the extent possible, what exactly was responsible for the great strides the city was making. In essence, I wanted to make sure that the reduction the city was seeing in new HIV infections was due to this intervention, not something else.

For instance, new HIV infection rates have been declining globally over the past decade: Was this just a local example of an international trend? And San Francisco’s demographics are changing dramatically as affluent tech workers displace African-American or Latino residents (not to mention the poor and working class, homeless individuals, drug users, sex workers, and many transgender people). Many of the exiled populations happen to have higher risks of becoming HIV-positive, so their absence, I surmised, could help drive down new infection rates.

“There's no question that the demographics of San Francisco are changing,” acknowledged Dr. Susan Buchbinder, director of Bridge HIV at the San Francisco Department of Public Health. That “could certainly affect the new diagnoses, because if we get fewer of a certain group living in San Francisco then we see fewer diagnoses in that group. But we can't say that that’s really what accounts for the numbers. We can't say that definitively.”

San Francisco has an army of highly skilled epidemiologists and statisticians hired, Buchbinder said, because “none of us can do all the analyses on our own.” (It bears noting that Buchbinder is herself a clinical professor of medicine, epidemiology, and biostatistics.) So, the idea that even this team of highly skilled professionals “can’t say” exactly what accounts for changes in HIV rates was a significant eye-opener. When media outlets report on declines of HIV rates, we rarely see caveats added about the difficulty of interpreting available data.

I went through 10 years of San Francisco HIV surveillance data and annual epidemiology reports. I asked Buchbinder about every change in rates of new HIV infections, particularly for different racial/ethnic groups.

“What do you think caused this?” I asked about increases and decreases in rates among the city’s monitored populations (for example, if there appeared an increase in the number of new HIV infections among African-American women). The fact that I was rarely provided a direct answer wasn’t due to some political stonewalling, but rather due to a problem with my questions, which were built on the apparently faulty assumption that those differences existed at all. Buchbinder maintained that most of the fluctuations in HIV rates over the past decade are simply not “significantly statistically different. The estimated number of new infections have remained relatively stable since 2007. There were fluctuations but … these small increases and small decreases often don't mean much.”

Small counties not only don’t have their own fleet of experts, they also have data that needs to be “interpreted with caution due to the small numbers,” Matt Geltmaker, the public health clinical services manager for the San Mateo County Health System, told me. “For example, just one case can change a percentage by 2 percent either way.”

Poor, partially rural Fresno County hovers around 100 new cases a year, so adding 10 new cases of HIV could significantly alter their per capita HIV rate.

Although the data San Francisco collects might not be able to tell what’s going on behind the scenes, at least its numbers reflect reality (as far as I can tell). I soon learned that might not be true of HIV data from other parts of the state. It all boils down to testing.

Until 2009, the state of California routinely conducted up to 130,000 HIV tests annually, then a recession-based decision led lawmakers to plunder the state’s Office of AIDS, cutting its budget in half, and completely decimating the department’s prevention funding.

“The amount of testing before, versus after the budget cuts was roughly cut in about half — the number of tests done annually was cut in half,” confirmed Karen E. Mark, MD, PhD, who has led the California Office of AIDS since 2010. To “partially mitigate” the impact, Mark told me that the office began limiting its testing to higher risk targets. “[So] while we still diagnose fewer people with HIV than we did before the budget cuts … the new amount of new diagnoses was not cut in half. Because we're testing people at higher risk. [Even with a lower] number of tests, we're diagnosing more people.”

Because of the loss of funding, a 2015 study reports, “HIV tests declined from 66,629 to 53,760 (19 percent) in local health jurisdictions with high HIV burden. In low-burden jurisdictions, HIV tests declined from 20,302 to 2,116 (90 percent). New HIV or AIDS diagnoses fell from 2,434 in 2009 to 2,235 in 2011 (calendar years) in high-burden jurisdictions and from 346 to 327 in low-burden ones.” Ultimately, the impact “was smaller than might have been expected,” because many jurisdictions reallocated funds to keep their testing programs afloat.

Mark also touted the department’s efforts at increasing “routine testing in medical settings,” where he said “the majority of new diagnoses are actually made,” and the only place “people who are not in sort of a high risk group are going to be tested for HIV.”

Kyle Baker, from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health's Division of HIV and STD Programs, dismissed routine medical testing as an idea that “sounds terrific on paper, but when it gets down to educating folks in clinics, thinking through their workflow and staffing patterns and things like that, on-the-ground experience has shown that it’s not as simple as it once seemed.”

In fact, the L.A. County Department of Public Health has had trouble convincing independent institutions (even facilities that the county funds) to adopt routine testing. One L.A. County hospital now has a “robust program,” Baker said, after “years of working and negotiating with the hospital administration.”

After the cuts, Baker says, Los Angeles (like San Francisco) “made the decision that we were not in any way going to decrease by one test the amount of testing that we fund. We refused to cut testing.” Instead, both jurisdictions increased testing in recent years.

Los Angeles was the only jurisdiction that provided us with data to compare new HIV cases with the number of tests given annually. What you can see from the chart they provided was that increases in testing have been mirrored by a rising number of new HIV cases. Generally, there were marginally more HIV tests given than there are new positive diagnoses, but during the 2014-2015 reporting period that has been released so far, HIV tests and new HIV diagnosis appeared to be neck to neck.

Is that merely a classic case of testing finally catching up to reality? A data expert told us that in cases where testing improves, incidences often appear to soar but it’s really because new testing uncovers older cases. What we should see is the rate of new cases flattening out, regardless of additional tests. L.A. may have reached that point, or their numbers could still change for 2015, as the data is collected and processed.

Meanwhile Fresno county’s testing was nearly abolished with the Office of AIDS budget cuts in 2009. This means that Fresno’s data isn’t as reliable. And when we see significant changes — say the decline of new HIV cases among African-American women in Fresno County — we can’t be sure if they reflect reality or an absence of testing among those populations or communities. If testing increases there, we will likely see rates climb significantly.

Making comparisons between these counties was made more difficult by the fact that they collect different data. Fresno reports, for example, don’t include “transgender” as a category. I was told they just didn’t have any transgender people with HIV in the county. That could be, though it seems unlikely when the HIV rates among African-American transgender women is hovering around 56 percent across the U.S. More likely, it could be that they — like many, many jurisdictions and most official medical studies and pharmaceutical clinical trials — still lump transgender women in with “men who have sex with men.”

Another example arose when we were deciding on art for the piece. I wanted a visual that showed the way testing can impact number of new HIV cases, but we didn’t have enough to compare all three counties. Rather than kick out the image, we ended up choosing to reproduce a graph of L.A. County’s testing data, in order to talk about the way testing impacts the data we were examining.

Lessons learned

So what’s a writer to do when faced with these sorts of circumstances?

Reporters dealing with data need to look beyond the reports based on that data, instead of accepting the reports' conclusions at face value. I actually uncovered mistakes in the annual epidemiology reports that were released from county sources. Most glaring was one from Fresno that showed HIV rates plummeting to zero — a result a little too good to be true. I recognized the problem because I’d seen a similar result when I was translating a data set to a graph. So when questions arose regarding the Fresno data, I compared it with Fresno-specific data from both state and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As a reporter, it’s a good start to ask if you can trust the numbers. Then look at the data collection methods, which you’ll likely learn are rarely uniform from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. You need to also ask, “Who is interpreting the data?” and understand why have they reached the conclusions they’ve made.

Instead of an army of epidemiologists, Fresno has one person, an employee who works part-time and has other duties as well. Talk about outgunned and overwhelmed.

As you do more data reporting, you get a better sense of whether conclusions fit the data, but otherwise all you can do is ask questions until you fully understand and check the answers twice. You have to talk to those who know the data the best, those who know how it was collected, what might be missing, and what it all might mean. If they can’t answer those questions, or you question their answers, you may need to take their data and have an expert interpret it for you (or, in a worst case scenario, tell you all the reasons it can’t be interpreted).

Finally, you must acknowledge these issues and problems you encounter with data in your reporting.

In the extended online version of the article, I decided to include a whole section talking explicitly about data (there’s another section on testing). It was quite similar to this essay, explaining how San Francisco’s numbers might be influenced by different factors; how the changes from year to year may not be significantly relevant; and the difficulty in comparing data when it is collected differently or not collected at all.

Data collection and interpretation is actually a significant part of San Francisco’s HIV prevention effort. They see testing as a tool for data collection, HIV prevention, and treatment. Studies show those who test positive change their behavior to reduce transmitting HIV. Testing positive is a prerequisite to getting antiretroviral treatment (shooting for Treatment as Prevention or TasP, where one on ARVs becomes undetectable and can no longer pass HIV on to a partner). Testing negative is a prerequisite to accessing PrEP, the once-daily prevention method colloquially dubbed the HIV-prevention pill.

The data won’t always be so integral to the story as it was here. But I think as journalists we need to look deeper into the reports and data we are provided, and to be as transparent as possible with our readers, by mentioning the variables involved in collecting, analyzing, and understanding data, and the conclusions we make based on it.

Read the story Jacob Anderson-Minshall discusses in this essay here.