How a flawed 1967 law affects California today. Can it be fixed?

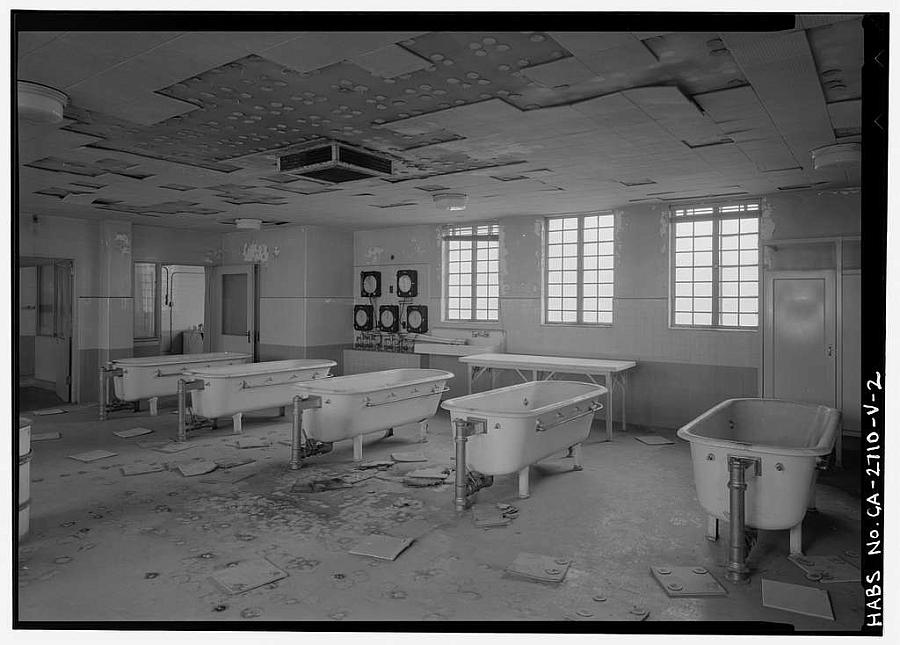

An abandoned wing of a state facility in Santa Clara, California.

On May 12, 2023, a 27-year-old man from Yreka knelt on the railroad tracks in Davis and appeared to pray as an Amtrak passenger train sped toward him.

Not far away on that same day, a man later identified as Carlos Reales Dominguez slashed a homeless woman through her tent. She survived.

Reales Dominguez grew up in Oakland, played high school football and was fastidious about his appearance. He got into UC Davis, where he studied biology and hoped to one day become a physician.

By 2022, however, his dark hair had grown wild and tangled, he stopped washing, eating and attending class, and told his girlfriend that the devil was talking to him. She didn’t know where to turn and no one at the university intervened. On April 25, 2023, UC Davis expelled him.

Two days later, authorities say, he plunged a knife into a 50-year-old man, David Breaux, who was sitting on his favorite bench, across from the town’s farmer’s market. Two days after that, in a park next to an elementary school, he stabbed Karim Abou Najm, a 20-year-old computer science student who was on the verge of graduating with honors. Both died.

Muckrakers in the mid-20th century had a name for the fetid state asylums that overflowed with more than half a million individuals diagnosed with mental illness, brain injuries and developmental disabilities: snake pits.

California led the nation by emptying and shuttering psychiatric hospitals. It came to be called deinstitutionalization. Then as now, too many people with severe mental illness were left with no plan to provide for their care. As we know all too well, America’s streets are the new snake pits, and its jails and prisons, the new asylums.

Like too many others, Reales Dominguez received help only after he was found incompetent to stand trial and sent to Atascadero State Hospital, though now, supposedly stable, he faces criminal trial later this year.

I wrote about the aftermath of deinstitutionalization many times during my years as a columnist and later editorial page editor at the Sacramento Bee, as senior editor at CalMatters, and as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times. Although I knew something of its history, the press of deadlines meant I could never fully research it.

Now, as a freelancer and author, I seek to more deeply understand the history and the politics of one of the worst public policy debacles of the last half of the 20th century.

That has led me to 1967, Ronald Reagan’s first year in office. He arrived in Sacramento offering a sunny vision of the California Dream, and vowed to cut taxes, reduce the size of government, and bring about law and order on the streets and calm on college campuses.

In that first year, he was hanged in effigy at Fresno State College, and he presided over the execution of a man who had tried to put off his date with death by slitting his wrists. He raised taxes to end a budget crisis and signed legislation legalizing abortion in California, five years before Roe v. Wade.

Two legislators, Assemblyman Frank Lanterman, a conservative from the wealthy suburb of La Cañada Flintridge, and state Sen. Nicholas Petris, a liberal who represented Oakland and Berkeley, pushed legislation to dramatically reduce the number of people confined to California’s state hospitals. They called their bill the Magna Carta for people with mental illness.

Reagan, who signed that legislation, often is blamed for what was to come, especially by Democrats. But is that blame justified? If overhauling the mental health care system was among his priorities, it wasn’t apparent from his early pronouncements.

And what exactly motivated Lanterman and Petris, and later, a less than enthusiastic third co-author, state Sen. Alan Short of Stockton? What dealmaking brought that bill to a vote on the final day of the 1967 legislative session? Why did other legislators vote in near unanimity to approve the measure? And what were the compromises that spurred Reagan to sign the bill?

I have a sense of the answers, having interviewed many people who were there and reading through old bill files housed at the Secretary of State Archives in Sacramento.

But there’s much more to know. To find answers, I intend to delve into the archives at USC, UCLA, the Reagan Library in Simi Valley, and the Hoover Institution at Stanford.

This much is clear: Politicians from both parties have found it expedient to duck the issue. Reagan was succeeded by a Democrat, Jerry Brown, then two Republicans, a Democrat, a Republican, and two more Democrats. Only one, Gov. Gavin Newsom, has elevated the issue to the top of his policy agenda.

I spent the bulk of my four-plus decades as a reporter writing about the confluence of state policy and politics. In the coming months, I intend to explore the politics and history of the complex issue of our mental health care system, and efforts to improve it.

Any change will have come too late for the man from Yreka, or Carlos Dominguez and the people he is accused of maiming and killing. But with public opinion polls showing that homelessness and mental health care have become top-tier issues, Sacramento politicians for the first time in decades are pushing to bring about significant changes to the mental health care system. And that is worth documenting.