Domestic abuse takes many forms, even in the absence of physical violence

This project was originally published in Nevada Current with support from our 2023 Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund

Alison stopped for gas in Carson City before driving to a medical appointment for her adenomyosis, a reproductive health condition that causes fatigue, fainting, and anemia when she realized she couldn’t pay because her card was rejected.

She went into Nevada State Bank, where she discovered the more than $20,000 in the joint account that she shared with her husband had been emptied.

“I love my kids to death, but I’d been begging for help with my reproductive health for 20 years,” said Alison, who didn’t want her full name used in this story. “The second I was no longer able to give him more children, which we weren’t going to do in the first place, things got really ugly, really quick. He drained all of our bank accounts when I asked for a divorce”

The teller at the bank directed her to Advocates to End Domestic Violence (AEDV), a private, nonprofit shelter in Carson City.

Before the surgery to treat adenomyosis, their relationship was already deteriorating, having been put under extra pressures by the death of her estranged husband’s grandfather during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the stressors of moving to Carson City from Fernley in Lyon County. She said he would control what clothes she wore, take her keys to prevent her from leaving their home to go to the gym, interfere with her seeing her friends or brother. When they separated, he would prolong the divorce and the selling of their house.

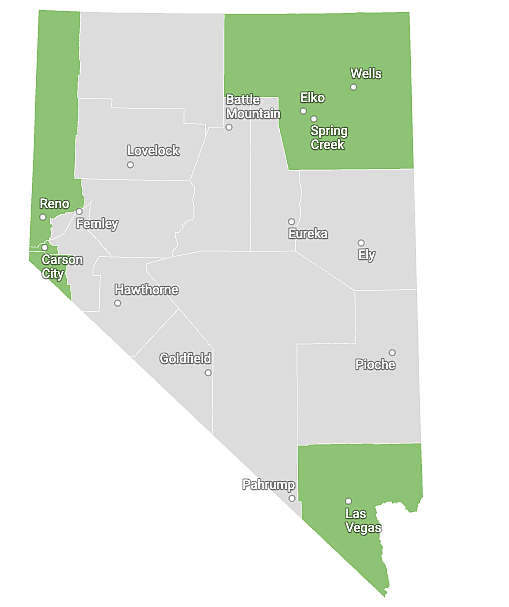

Domestic Violence Shelters in Nevada

All 17 counties in Nevada have a domestic violence program in place, but not every county has a designated shelter. Many people in Nevada’s rural and frontier counties are either placed in the state’s urban counties that have shelters or are placed in hotels and motels throughout the area.

Nevada Coalition to End Domestic Violence 2022 statewide Data Collection Project

Domestic abuse can take many forms even in the absence of physical violence.

Domestic violence and abuse exist on a spectrum where power is used to control another person. In addition to physical and sexual violence and emotional and verbal assaults, domestic abuse can extend to controlling finances, destroying property, isolating a person from friends, family, and community, threatening to commit suicide, and using children to control someone.

More than 90% of domestic violence survivors experience economic abuse, which can include applying for loans or credit cards in the victim’s name without their permission, refinancing a home without a victim’s knowledge, forbidding them to work, and repeatedly filing costly lawsuits during separation.

The state doesn’t provide litigation protection, safe banking protections, or coerced debt protections, according to FreeForm, a collective grassroots movement on the intersection of domestic violence and economic abuse.

The consequences of domestic abuse can cause harm to the victim long after the immediate threat is gone.

“I grew up in a very violent home, I had to put my dad in prison for being a pedophile, and got put in foster care really late,” Alison said. “I had gone through 10, 15 years after I aged out of the system where I just was floating through life. This is the end of my second marriage because I was never taught to believe or love in myself, I wasn’t taught that so many of these behaviors were not normal, not acceptable. For me, it was a normal thing as long as I wasn’t getting punched in the face.”

According to a Carson City Sheriff’s report from December 2022, Alison told officers that her husband had never been physically violent toward her, but she was still concerned about her safety.

Finding safety and shelter

Domestic violence is the leading cause of homelessness for women and children in the U.S., and economic abuse creates barriers to housing security. The problem is compounded when survivors can’t get into domestic violence shelters, a not uncommon circumstance in Nevada.

In addition to the AEDV facility in Carson City, there are eight other domestic violence shelters in Nevada. Only two of those are outside the state's most populated counties of Clark and Washoe, the Family Support Center in Douglas County, and the Committee Against Domestic Violence Harbor House in Elko County.

The only state funding domestic violence providers receive is through marriage certificate fees. Nevada does not have any designated funding for shelters in its budget, and relies on federal grant funds for other programs that support domestic violence efforts.

Nevada has a shortage of beds for domestic violence survivors. The state did receive funding through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) for housing vouchers. Still, the state, Clark County, and the City of Las Vegas all rejected the proposal from SafeNest, the domestic violence emergency shelter and treatment center, to use ARPA to fund a new building with over 300 beds.

While every county uses those funds to provide some form of domestic violence programming, there’s not enough to create a shelter in each county, said Lisa Lee, the executive director of AEDV. The Carson City shelter at AEDV has over 50 beds and serves people from across the state including the surrounding rural counties like Lyon, Churchill, and Douglas.

“You’re probably going to come into Carson, and once you get into Carson and we’re going to start working with you, and if you don’t want to go back to your county for whatever reason — he’s there, you don’t have a job, you don’t have a car…our goal is to get you comfortable in those first couple of days,” Lee said.

The nonprofit is currently building a new shelter that will house 38 people in Carson City and is estimated to open in spring 2024. The shelter is being funded through their thrift store, community donations, and a William N. Pennington Foundation grant after banks denied the nonprofit a loan because “if we could not repay the loan, they would not want the publicity of foreclosing on a shelter,” Lee said.

“You’ve just moved into a strange place, you never thought you’d be in a shelter, you have your children,” Lee said, noting that the new shelter aims to address the cultural shocks of moving into domestic violence, including sharing space with other women, children, and families, having a curfew, and keeping their location private for others' safety.

Alison knows those challenges firsthand — she shares three children with her estranged husband, two from a previous marriage that he adopted and one child they had together. When she left over a year ago, her three children and Alison moved into the shelter.

Lisa Lee, Executive Director of Advocates to End Domestic Violence, works on paperwork for the nonprofit's new shelter.

Photo: Camalot Todd/Nevada Current

“It got to the point recently where he was starting to make fun of the kids and finally it clicked, that’s not something I would ever allow for the kids, why would I allow that for me?” Alison said.

Nevada’s persistent struggles with childcare, housing, transportation, and other social determinants of health exacerbate the barriers to leaving abusive households.

“Our counties are pretty huge, and without transportation, you’re lost in this state,” Lee said.

But that’s only one piece of the equation.

“You’re talking daycare, it’s very limited, it’s very hard to find and it’s very costly. Then you’re talking employment, trying to find a job, trying to find a job that works with daycare. Housing, I don’t know what you’re paying for rent, but it’s expensive and you’re not going to make it even at $15 an hour,” Lee said.

Courts, custody, and children as an abusive mechanism

Nevada ranks fourth in the nation for the rate of interpersonal violence, and 44% of Nevadan women experience domestic violence in their lifetime, compared to 35% nationally, according to a University of Nevada Las Vegas research brief.

“The amount of people who have been through the same situation, it’s overwhelming. The lady who helped me get into the college here, she was talking about her experience, the counselors shared their experiences, and some of the teachers — and it’s so pervasive,” said Alison, who was able to continue her education after she and her children moved into the AEDV shelter.

Children complicate the ability of victims to leave their abusers, Lee said.

While the person experiencing domestic violence may be granted a temporary restraining order, as Alison was, victims typically must share custody with their spouse until a divorce is final, or beyond.

I wasn’t taught that so many of these behaviors were not normal, not acceptable. For me, it was a normal thing as long as I wasn’t getting punched in the face.

The perpetrator of the abuse can use the courts and children to maintain contact with their victim by prolonging legal cases, seeking full custody, increasing visitation time to cause them distress, lying in court as a tactic of control and not following court orders, according to a 2022 National Institutes of Health report on coercive control in the judicial system. The report urges the development of a scale to quantify legal abuse, citing a current absence of legal definition and measurement.

Alison’s adenomyosis appointment was in August 2022, she got her first temporary restraining order in September of that year and was living in the shelter with her children, as she and her estranged husband sorted out their legal details.

She called the police, but when they arrived they told her they couldn’t do anything, she said.

The police are limited to the evidence provided, and encourage people to document as much as possible including recording interactions with abusers, like text messages, because police need probable cause to arrest the person who violated the restraining order, said Jim Primka, the assistant sheriff for the Carson City Sheriff’s Office.

The second time Alison’s husband violated the restraining order, she had moved out of the shelter, and into her own apartment unit through subsidized housing and was in the Nevada Confidential Address Program (CAP) which helps people experiencing domestic violence, sexual assault, human trafficking, and stalking from being located by the perpetrator through public records by providing a fictitious address and confidential mail forwarding services. Alison believes he either followed her after she had dropped off the children for his visitation rights or tracked one of the children’s phones.

Police departments don’t actually have to enforce restraining orders. In 2005, the United States Supreme Court ruled 7–2 in Castle Rock v. Gonzales that a town and its police department couldn’t be sued for failing to enforce a restraining order after a mother’s three children were murdered by her estranged husband.

Alison, who graduated from the Advocates to End Domestic Violence program, shared her experiences of financial abuse and stalking in the last two years.

Photo: Camalot Todd/Nevada Current

“The biggest barrier for me was not feeling supported by law enforcement. That’s a big one. I think that’s why a lot of people don’t report. Because why am I going to go through making him upset if there is no accountability?”

Over a year after she moved into the shelter, she and her estranged husband are not divorced. The court date has moved back several times. But between the fear, the stress, and the anxiety, she knows she made the right decision.

“Absent the issues I’ve been having with accountability, it’s been so freeing feeling like for the first time I can figure out who I am and what I like and it’s also so frustrating because I feel like I lost so many years and I don’t have an answer as to why I couldn’t do that then what I did now,” Alison said. “I’ve had a lifetime of going through this. I don’t want to be in this situation ever again. I deserve better. My kids deserve better.”