FORT BELKNAP RESERVATION — Less than 200 feet from her driveway on a morning in August, the retired cop car Tescha Hawley drives for work began to slow. Hundreds of people waited on the other end.

'The gap filler': One woman's mission to improve health outcomes on Fort Belknap Reservation

The story was originally published by the Missoulian with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

“Oh no,” she said. “No, no, no.”

She pulled into a neighbor’s driveway just as the 1988 Crown Victoria died.

“I don’t have time for sh-- to break down,” Hawley said, hitting her hand against the steering wheel. “I have too much to do!”

Tescha Hawley has made it her life’s mission to improve life expectancy on the Fort Belknap Reservation. Through her work with Day Eagle Hope Project, a nonprofit she launched, Hawley aims to provide resources including fresh produce, gas cards and travel for those in need of medical attention across the reservation. “I’m just a gap filler,” she said. “But sometimes it feels like I am the filler.”

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

Life expectancy is Hawley’s mission. Herself a cancer survivor, she knows death comes too soon for Indigenous people in America and even sooner for people on the Fort Belknap Reservation in north-central Montana where she lives.

Buster Moore helps distribute boxes of produce to people in Hays, a town 35 miles south of the distribution hub for Day Eagle Project in Fort Belknap Agency. While there are a handful of convenience stores on the reservation, residents often must travel to an Albertsons grocery store just outside the reservation for healthy food. Depending on where one lives on the reservation, a trip to that store could be 40 miles each way.

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

Frustrated by a health care system that consistently fails Indigenous people and elected officials who don’t seem to prioritize the issue, individuals like Hawley often work to fill gaps in the system. While her mission isn’t easy, Hawley knows her efforts save lives.

That’s why on this particular summer morning, Hawley planned to distribute tens of thousands of pounds of fresh produce to her community. It’s why she drives people to medical appointments and hands out gas cards. It’s why she helps community members navigate a complex medical system and encourages them to seek preventive care. And why she launched her nonprofit, Day Eagle Hope Project, which recently received national recognition.

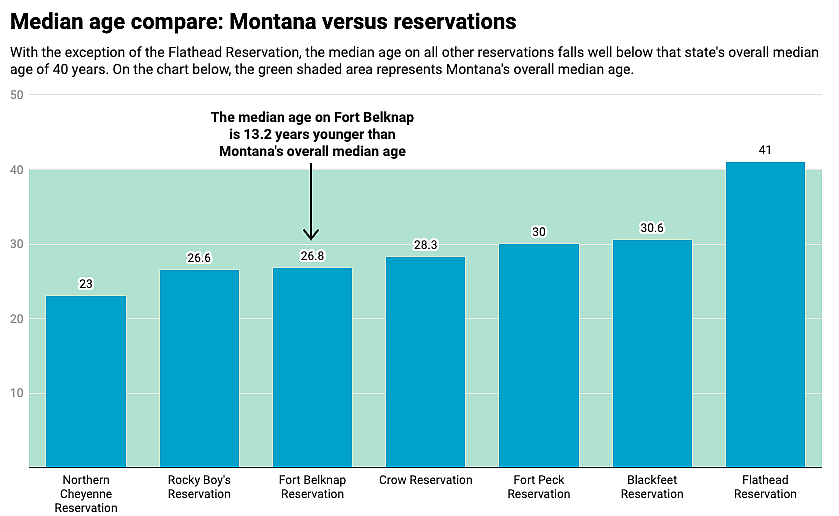

Native Americans have the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S. And in Montana, where Native Americans comprise 6.7% of the population, Indigenous people die a generation younger than their white neighbors.

Experts say inadequate care, food deserts, discrimination at the doctor’s office, oppressive policies, poverty and rurality are among the factors contributing to the crisis. And while tribal leaders have raised the issue for years, they say improving health outcomes simply isn’t a priority among state and federal leaders.

From 2018 to 2022, white Montanans died on average at 78, and Native Americans in the state typically died 17 years sooner at 61. On the Fort Belknap Reservation, the gap widens. The most recent county health assessment reveals that on the reservation, Native men die, on average, at 56. In the same county, white men typically live 27 years longer.

Hawley — like others who do this work in tribal communities statewide — is up against intense barriers. She doesn’t have a proper food storage facility or a central distribution point. Hawley has no full-time staff. And the people who help her often don’t have reliable vehicles.

Limited resources mean Hawley constantly scrambles for funding. Political dynamics bring further complications. And, of course, Hawley must also grapple with her own health issues.

Hawley is the first to admit that individual efforts aren’t enough to fix a broken system of care. She alone cannot ensure the federal Indian Health Service is adequately funded. She can’t help that some of the closest medical services are hundreds of miles away. She can’t change the fact that almost one-third of families on the reservation live below poverty level or that most towns on the reservation have a convenience store — not a grocery store.

“I’m just a gap filler,” she said. “But sometimes it feels like I am the filler.”

In the driver’s seat of the retired cop car, Hawley took a deep breath and sighed as her phone pinged with Facebook messages from community members: “Where is the food distribution going to be? When does it start? Is food distribution today?”

For her work on the reservation, Tescha Hawley uses a retired 1988 Crown Victoria police cruiser supplied by the tribe. Unreliable, the vehicle broke down just as Hawley was to set out for a day of food distribution in late August. “I don’t have time for sh-- to break down,” she said. “I have too much to do!”

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

The car was the least of her problems.

Hawley had scrambled to move her food distribution site after one tribal building was condemned for black mold. And she'd recently heard that tribal housing employees, who usually haul food on large trailers, were unavailable.

Hawley, who is Aaniiih, has wavy blonde hair, big brown eyes and isn’t afraid to speak her mind. Sitting in her stalled car on the side of the highway, she had to find a different way to distribute 26,000 pounds of fresh produce across the 1,000-square-mile reservation.

She grabbed her phone and opened Facebook.

In a place where there’s no local newspaper, where cell service is limited and where there aren't many areas for community members to convene, Facebook — which requires low bandwidth and is accessible to elders — is a vital tool of communication.

“Good morning,” Hawley typed in a post. “We will be delayed this a.m.”

‘Twenty-six should not be middle-age’: IHS struggles to provide quality care

Indian Health Service (IHS) is responsible for providing health care to federally recognized tribes.

While tribal members statewide criticize the agency for being understaffed and underfunded, agency leaders say IHS faces unique challenges in providing care.

Jessica Windy Boy, former CEO of the Fort Belknap IHS facility, knows firsthand that barriers to care can mean the difference between life and early death on the reservation. Her uncle, a rancher, died at 56 of diabetes.

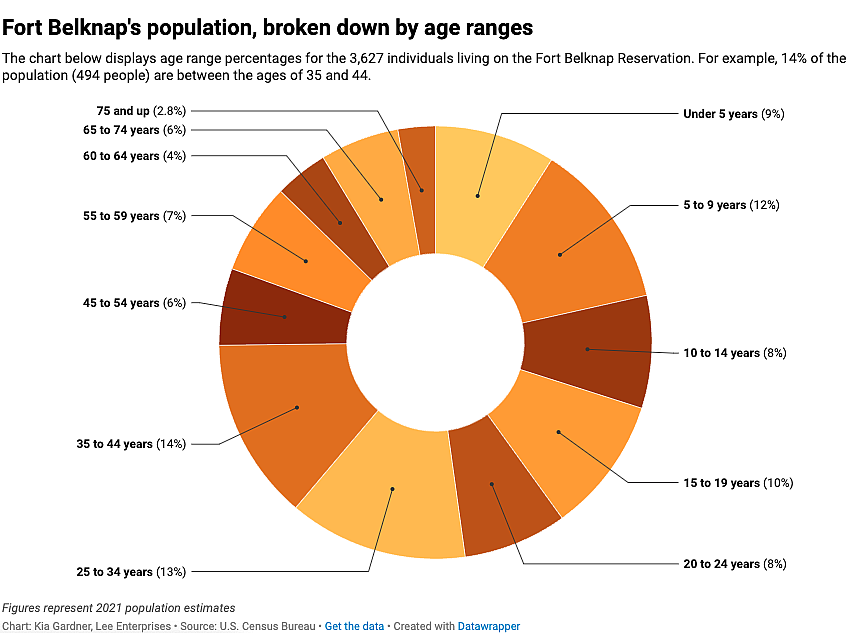

“There’s tons of 80- and 90-year-olds in Montana — just not here on the reservation,” she said. “Twenty-six should not be middle-age.”

The two hardest things to do in government, according to Windy Boy, are hire someone and buy something.

IHS facilities everywhere face severe staffing shortages. In August, 42 of the roughly 200 positions at the Fort Belknap IHS unit were vacant, which, at the time, was the best vacancy rate of all seven IHS facilities in Montana.

Because the IHS doesn’t provide most specialty services, people must often drive 200 miles each way to Billings, 160 miles to Great Falls or 50 miles to Havre for things like cancer treatment, a CT scan or dialysis.

The IHS has a van, but it can only comfortably transport three people at a time — limiting its effectiveness.

Of the seven IHS facilities on reservations in Montana, Windy Boy said the Fort Belknap IHS unit is the only one that runs ambulance services.

But transport can also be dangerous. The Fort Belknap IHS does not have a blood bank. Ambulance drivers — who can log thousands of miles a week on unlit, rural roads — often work overtime and face high rates of burnout. Plus, there’s the deer problem. Windy Boy said EMS drivers hit so many deer that one seemingly invincible ambulance earned the nickname “Deer Slayer.”

An IHS bus would help more people access care. In August, Windy Boy wasn’t optimistic that resource need would be met. IHS funding is appropriated through Congress, and money for each facility is limited.

“I can’t depend on money from IHS if I want to grow a program or service,” she explained. “I have to find that through a third party. No other hospital has to think about how to fund EMS.”

Almost one-third of families on the reservation live below poverty level.

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

‘Why are we living like this?’: Resources are limited

After abandoning her car on the side of the road, Hawley jumped in her personal truck back at her house. On a food distribution day, she could easily log more than 100 miles just driving on the reservation alone, so she typically tries to avoid putting miles on her own vehicle.

Today, however, she had no choice.

Arriving at the community center, Hawley watched as her friend Trisha Blackcrow — a short woman with long brown hair — used a forklift to hoist pallets of food boxes, stacking them like Tetris blocks into the beds of pickup trucks.

Trucks loaded with boxes of food are dispatched to towns on the reservation.

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

With the original food distribution building condemned, the tribes’ community center was Hawley’s best option. One major problem, though, is that the building doesn’t have heating or cooling. In the August heat with no walk-in refrigeration, Hawley figured she had 24 hours before the lettuce would wilt and the celery would soften.

“Why are we living like this?” she shouted to no one in particular. “There’s no damn reason!”

Once they were loaded with boxes of food, truck drivers headed out to towns on the reservation, where there are about three people per square mile. One traveled 25 miles east to Dodson, another 35 miles south to Hays and a third 40 miles southeast to Lodge Pole. Another driver took a truckload of produce to the Rocky Boy Reservation, 70 miles west of Fort Belknap.

In Hays, cars pulled up every few minutes to get boxes filled with lettuce, celery, cauliflower and onions.

A grandmother thanked the group, saying she relies on Hawley’s food distribution to feed salads to her grandchildren. A man in a tank top leaned out of his powder blue minivan and shouted, “I love you guys!”

Hawley yelled as a red SUV sped past blaring music.

“Hey!” she shouted. “Get over here!”

The car’s wheels screeched as the driver spun a U-turn and pulled up. Inside, four young men smiled and joked with each other as Hawley loaded a box in their trunk.

“You can grind that cauliflower up and make rice, you know!” she told them as she closed the trunk door.

Michael “Conrad” Buck unloads boxes of produce to be distributed to people on the Fort Belknap Reservation.

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

While there are a handful of convenience stores on the reservation, residents often must travel to an Albertsons grocery store just outside the reservation for healthy food. Depending on where one lives on the reservation, a trip to that store could be 40 miles each way. In a place where the median household income is $46,250 — about $20,000 less than Montana’s statewide median and about $28,000 less than the national figure — not everyone has a reliable vehicle or money for gas or for produce, which is typically more expensive than food at a convenience store.

Lack of access to healthy foods, experts say, contributes to poorer health outcomes. Nationally, Native Americans are 3.2 times more likely to die from diabetes than non-Natives. In Montana, where most reservations are considered food deserts, Natives are 4.5 times more likely to die from diabetes than their white neighbors.

Hawley knows she could be more effective if she had more resources. She wants a centrally located building, with a covered loading dock, heating, cooling and walk-in refrigeration for adequate food storage. Reliable vehicles and paid employees would improve food distribution efforts. If Hawley had a bus, she could also transport people to medical appointments across the state. And if she had a reliable car herself, maybe she wouldn’t have been late on this August morning.

Hawley disburses more than $20,000 twice a month to buy and ship produce to her community. She doesn’t get paid for her nonprofit work, and it’s not her full-time job. To make ends meet, she serves as a mental health therapist at Harlem Public Schools, earning $42,000 a year. Hawley typically submits grant applications for her nonprofit on nights and weekends, sometimes staying up until 2 a.m., and she takes time off work to distribute food across the reservation.

To make ends meet, Hawley serves as a mental health therapist at Harlem Public Schools, earning $42,000 a year. Often, she will take time off work to distribute food across the reservation.

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

While the Fort Belknap Aaniiih and Nakoda Tribes provide financial assistance to members seeking medical care, leaders say the support drains tribal resources.

Mark Azure, former tribal president, said while the tribe budgets for medical assistance, it’s impossible to predict how many people will get sick in a given month, so budgets often fluctuate in unpredictable ways. Tribal officials said the tribes distribute between $60,000 and $90,000 each month to help members pay for gas, food and hotels to get to medical appointments.

Michael “Conrad” Buck fuels up trucks loaded with produce headed to the Rocky Boy Reservation.

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

Azure said budgeting can be especially burdensome for rural tribes, like the Aaniiih and Nakoda. At a conference with tribal leaders nationwide, Azure remembers people spoke of things like a tribally-run golf course in Las Vegas, an offshore drilling site in the Gulf of Mexico or a big hotel or casino — all of which earn outside revenue for tribal communities.

Even small tribes can have big revenue streams. Take the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux in Minnesota. Profiting largely from casinos and resorts that attract thousands of people each year, the tribal community of 779 people has a net worth of more than $2 billion.

But tribes on the Fort Belknap Reservation — which is home to less than 3,500 people in rural Montana — don’t have the same opportunities.

“There aren’t a lot of people here,” Azure said. “The demographics are small. So, I don't know how you could build a huge casino. It’s not, ‘If you build it, they will come.’ You can build it, but that doesn’t mean they’re coming.”

Jeffrey Stiffarm, president of the Fort Belknap Aaniiih and Nakoda Tribes, said Hawley would need a majority vote to get more resources for her work. “It’s not (that people are) against what she’s doing,” he elaborated. “It’s how she approaches (councilmembers) to get it done. She’s very upfront. She’s very, maybe sometimes, too pushy for them. … (But) I do my best to try to help her accomplish the things she’s trying to get done.”

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

As community members from different tribal programs helped load and unload boxes of produce, Hawley noticed a group that wasn’t there — the tribal council.

Hawley isn’t afraid to voice her frustration, but being outspoken, she said, comes at a price in the small, tight-knit tribal community.

When asked about the council’s apparent lack of support, President Jeffrey Stiffarm said Hawley would need a majority vote to get more resources, and, “If we put it to a vote, I don’t think she’d get her way.”

“It’s not (that people are) against what she’s doing,” he elaborated. “It’s how she approaches (council members) to get it done. She’s very upfront. She’s very, maybe sometimes, too pushy for them. (But) I do my best to try to help her accomplish the things she’s trying to get done.”

Hawley knows this is her reality.

“If you want to get things done here,” she said, "you have to do it yourself."

'I pray someone would step up': Future uncertain

Hawley knows more than anyone that it’s important to stay on top of her own health. But she resents the fact that she must leave her community — and the hundreds of residents who depend on her — to get the care she needs.

While Hawley is cancer-free, she sees a doctor in Billings to ensure her own nutrition levels are stable.

Tescha Hawley embraces her daughter, Tearia Sunchild, before she leaves their home. Hawley named Day Eagle Hope Project after her daughter whose name, “Kisikahw Kihiw Iskwesis," translates to “Day Eagle Girl.”

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

Once food distribution was complete and after Hawley had visited with several cancer patients, after she had counseled students at school and coordinated concessions for the next sports game (advocating for healthy options), Hawley would have to pack a suitcase, and her aunt would drive her three hours to Billings. Together, they’d stay the night in Hawley’s niece’s basement apartment on a pull-out couch and drive home the next day.

At 52, Hawley is nine years younger than the average age at which Native Americans die in Montana.

If she were to die tomorrow, Hawley knows it would be nearly impossible to find someone to fill her unpaid position. She invests almost as much time in her volunteer work as she does her full-time, paid job.

“I pray that someone would step up,” she said. “(But) I know that would be difficult. I had to get a paying job just to feed my own children. (It’s) difficult managing two full-time jobs.”

‘I reached out to Tescha’: Assistance saves lives

Bret Kuntz works as a cashier at the Kwik Stop in Fort Belknap Agency. At 54, Kuntz was diagnosed with colon cancer and reached out Tescha Hawley for help with gas cards to get him to and from his appointments in Havre. His surgery was successful and trips have become less frequent. “(Without Hawley), I don’t know exactly what I would’ve done,” he said. “I would’ve found a way, probably, but I just don’t know.”

BEN ALLAN SMITH, Missoulian

Before leaving town, Hawley pulled into the Kwik Stop gas station to fuel one more truckload of food.

A mug of coffee balanced haphazardly in one cup holder, and a plate of half-eaten strawberries wobbled on her dashboard.

“Need some gas?” Bret Kuntz, a cashier at the Kwik Stop, asked Hawley as she walked in the convenience store.

Kuntz, who’s been working at the Kwik Stop for two years, knows firsthand the power of Hawley’s work.

Six months earlier, Kuntz, 54, was diagnosed with colon cancer. He took time off work to travel 50 miles each way to Havre for treatment. When he got surgery, he had to take four months off work to recover. He drained his savings in trips to and from appointments.

“I reached out to Tescha,” he said. “She helped me out with gas cards and anything financial that I needed. That was a real godsend.”

Kuntz’s surgery was successful, and his trips to Havre have become less frequent. He prides himself on knowing almost everyone in the small community and is relieved to be back at the Kwik Stop where he enjoys chatting with people as they come and go.

“(Without Hawley), I don’t know exactly what I would’ve done,” he said. “I would’ve found a way, probably, but I just don’t know.”