Health Officials Knew COVID-19 Would Hit Pacific Islanders Hard. The State Still Fell Short

This article is part of a larger project by Anita Hofschneider with the help of the 2020 National Fellowship and a grant from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Her other stories include:

Community Leaders: State Is Failing Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 1: Hawaii Wanted To Save Insurance Money. People Died

Hawaii Researchers: State Must Support Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Pacific Islanders Have The Highest COVID-19 Death Rate In Hawaii

Women Were Already Struggling At Work. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

Here’s What Honolulu Is Doing To Test Hard-Hit Communities For COVID-19

Kalihi Has The Worst COVID-19 Outbreak In Hawaii. Here’s How The Community Is Responding

Hawaii COVID-19 Data For Race And Ethnicity Is Missing

Hawaii Pacific Islanders Are Twice As Likely To Be Hospitalized For COVID-19

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 3: Pacific Islanders Can’t Return Home During COVID-19 — Even To Bury Their Loved Ones

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 4: The Pandemic Is Hitting Hawaii’s Filipino Community Hard

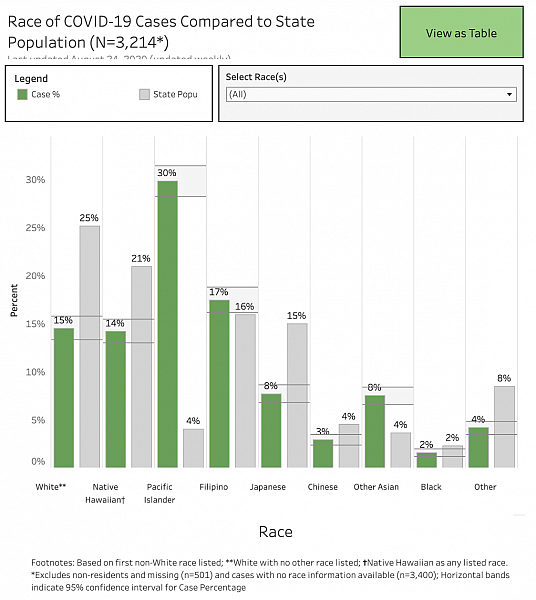

Members of Hawaii’s COVID-19 Command Mobile Unit prepare to collect samples from Oahu residents during a drive-thru event in Kakaako. Pacific Islanders make up nearly a third of cases in Hawaii.

For the past four months, Eola Lokebol has been overwhelmed with calls from Marshallese families in Hawaii desperate for help because they or their loved ones have tested positive for the coronavirus.

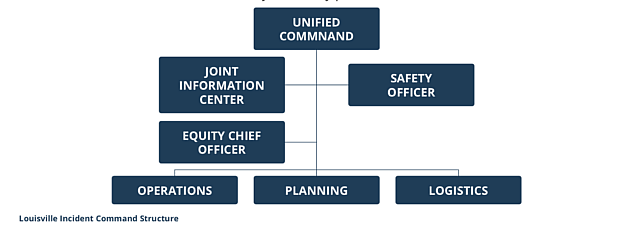

Melissa Jones, the executive director of the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative, says that having emergency response staffers who are tasked with addressing health equity is critical. Her organization just released a new report highlighting best practices for addressing health disparities in pandemic response teams.

Emergency response operations are often very centralized, Jones says, and there needs to be someone in the decision-making room who understands the needs of different communities.

“The only way you know that is if you have a health equity officer whose whole job is to focus on what different communities need who are most impacted and to develop the strategies that are going to work for them,” she said.

Lokebol says she’s seeing more outreach from officials now, such as public health nurses who have helped with food distribution. The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency and the nonprofit group EveryOne Hawaii donated more than 20,000 masks to the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander response team, a community coalition formed in response to the pandemic.

Hawaii health department staffers have been going door-to-door to offer testing in low-income communities and have translated some COVID-19 messages into different languages. Community members say they are extremely grateful for the help of individual Health Department staffers, even if overall they feel their community has been overlooked.

The Hawaii Department of Health created this video in Chuukese to spread the word about coronavirus.

Hawaii Health Director Bruce Anderson and Park did not respond to multiple requests for interviews for this story. State health officials say health equity is a priority and is embedded into their pandemic response.

The difference between Hawaii’s outreach to Pacific Islander communities and other states’ is noticeable, says Jayceleen Ifenuk, who is part of the Federated States of Micronesia COVID-19 Task Force. Ifenuk moved to Hawaii from Chuuk when she was eight years old, lost her job in Honolulu when the pandemic hit and moved to Oregon two months ago to save money and live with family.

She was surprised to see how much more collaborative Oregon’s coronavirus response has been with Pacific Islanders there compared with Hawaii.

“It’s frustrating that after all these years, we’re still the forgotten group that kind of doesn’t matter,” she said. “We’re more of an afterthought.”

Hawaii’s Office of Health Equity, launched in 2011, was small, with only one full-time staffer. It was a policy-focused office, with the goal of influencing the health department’s work by providing staff training, increasing community input and ensuring that health equity is a priority throughout every aspect of the health department. The plan, according to a draft reviewed by Civil Beat, was to build it out and create a permanent division.

Other versions of the office nationally are more robust. In California, the Office of Health Equity produces reports on disparities in health care, convenes community leaders from underrepresented communities and pushes for better health equity-focused policies throughout the state, not just the health department.

Lorrin Kim, who leads the Office of Policy, Planning and Program Development at the Hawaii Department of Health, said the Office of Equity lost its director in 2015 after the Legislature passed new rules limiting how the state could use special funds.

Along with then-Health Director Virginia Pressler, he remembers debating whether to use remaining money to continue the health equity work on a smaller scale or funnel it into a position that would seek to expand telehealth, which felt more tangible and achievable.

Hawaii hasn’t staffed the Office of Health Equity since 2015.

The decision was also influenced by the question of whether the health equity office was necessary. Kim remembers going to conferences on the mainland and feeling like concerns about access to health care there weren’t as relevant to Hawaii because Hawaii is a minority-majority state with a relatively low rate of uninsured people.

“We had great aspirations, but we really struggled with how to reconcile the national best practices and trends with Hawaii,” he said. “It was difficult to replace Asian American with Filipino or Hispanic with Native Hawaiian. It wasn’t an easy substitution. We have a pretty progressive state health environment. Clearly there are levels of institutionalized racism here but it is so stark on the mainland.”

He wondered whether a health equity division would be duplicating work done by Native Hawaiian-focused organizations like the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. And he felt policy work about Pacific Islander migrants wasn’t going to be effective until the communities were better organized politically, given that politicians were mainly concerned about the cost of their health care, not providing it.

“No amount of government programming will get very far without the constituents actively advocating on their behalf,” he said of Pacific migrants who are present in Hawaii through treaties known as the Compacts of Free Association. The community does have advocacy groups but they tend to have limited resources.

“When people talk about COFA they talk about how much it costs. That’s where the conversation just kind of simmers. That’s really all people talk about,” Kim said, adding that people don’t talk about barriers in accessing health, such as language interpretation needs. “The COFA conversation is about how many general funds we’re spending and not about solving the problem.”

Kim wants to get funding to reestablish the health equity office but said that will have to wait because of the pandemic-induced hiring freeze.

“Everybody would agree that we need to do more about health equity and having dedicated resources certainly would help that,” he said.

Joseph Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, chair of the Native Hawaiian Health department at the University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine, says even when the office was in existence, it didn’t have adequate staffing or authority to be effective. He thinks addressing the needs of Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders should be a priority in every division of the Department of Health.

He’s not surprised Pacific Islanders are suffering the most from COVID-19 because they’ve always been neglected by the state.

“It’s an example of how we just allow these inequities to continue and when we’re in a time of crisis it just gets worse and then we don’t know what to do about it because we never really addressed these issues,” he said.

Improving Outreach

Lola Irvin is the head of the chronic disease prevention and health promotion division at the Department of Health. She says that she is one of several division heads who joins pandemic response calls every day and cares deeply about health equity.

The health department has been conducting door-to-door outreach at public housing developments since May and established language interpretation services on Hawaii island’s health division over the summer. The agency has an Office of Language Access that has produced videos and run radio ads about COVID-19 in multiple languages.

Health equity is “integrated into everything we do, our plans, our implementation, our languages in terms of how we speak and making sure we’re addressing it,” she said.

But top health officials haven’t expressed that same sensitivity and awareness. In early April, Hawaii’s health director Bruce Anderson told reporters that he didn’t expect to see the racial disparities in the pandemic that have emerged in other states.

“I think everyone is pretty much (in) the same socio-economic group, except perhaps some of the Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders,” he said, even though data shows poverty varies widely in Hawaii by race and ethnicity.

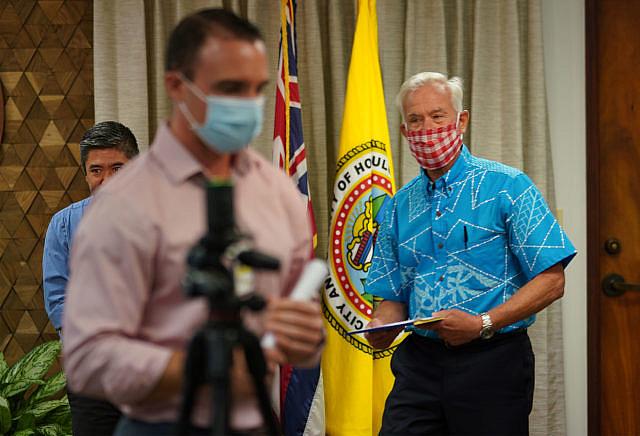

Health Director Bruce Anderson said in April that he didn’t expect Hawaii to see the same racial disparities as other states.

Anderson later apologized to the Marshallese community in Kona in May after he singled them out. There’s no public data that indicates that Marshallese families have contracted COVID-19 more often than other Pasifika communities.

When Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander leaders met with Park, the state epidemiologist, last week, they left feeling discouraged, telling reporters that she was unwilling to move forward on any of their recommendations to better track the virus in their communities.

Among other changes, they want the state to hire Pacific Islander contact tracers and provide gift cards to quarantined families who can’t use food stamps for food delivery.

Jendrikdrik Paul, who leads the Marshallese Community Organization, says given how vulnerable the Pacific Islander community is to the virus, he’s unsure why the Department of Health hasn’t relied on community groups like his.

“I think they could have reached out to the community just in case this happens. We could have been ready to offer our help,” he said, adding he knows of four people living in crowded units still waiting to hear whether the state can offer them a hotel room.

Paul thinks Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell was spot-on when he said at a recent press conference that there’s a need to do more to help Pacific Islanders.

“In some ways, I think we forgot about this community,” Caldwell acknowledged.

Better Collaboration Elsewhere

Jones from the Bay Area health organization analyzed pandemic responses nationally and found health departments in California, Washington and Kentucky were better equipped to respond to racial disparities in the pandemic because of existing staff dedicated to addressing them.

Jones says that in San Francisco, having health equity-focused staffers enabled the city to more quickly identify virus hotspots and set up a housing program to isolate sick people.

In Seattle-King County the public health department set up a Pandemic Community Advisory Group to ensure the communities who were most likely to be affected by COVID-19 were involved in the response. That enabled the county to better get out messages about wearing masks and social distancing through trusted community leaders, Jones said.

Joe Enlet is the FSM consul general in Portland, Oregon.

Like Hawaii, Oregon data showed Pacific Islanders had the highest rate of COVID-19 back in April. Joe Enlet, consul general of the Federated States of Micronesia in Portland, said Oregon officials reached out to him and other Pacific Islander leaders right away.

“We have been part of conversations in trying to shape the response in both the state health department and local health department authorities,” he said. “It’s basically just activating those relationships that have been created over the years so I think that’s why it’s been pretty quick for them to respond.”

Oregon gave the COFA Alliance National Network about $300,000 to hire Pacific Islander contact tracers, one of several grants to Pacific Islander community organizations, Enlet said. Every week state officials hold meetings with community organizations to discuss the COVID-19 response.

It’s not perfect — Enlet says he wishes resources could be distributed more quickly and says historic lack of investment in community organizations makes it difficult to scale up quickly. But he thinks having state and local officials who are charged with ensuring health equity is essential.

“There’s a path for advocacy and a path for accountability,” Enlet said. “Even if it’s late or not enough, at least there’s a place where people can go to and hold people accountable. To not even have that path, where do we go from here?”

Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell says he wants to help. He said the city is in the process of contracting with a 130-room Waikiki hotel to provide rooms for sick people who need to isolate, and has plans to potentially contract with two more hotels.

“We need to do a better job of not forgetting these new immigrant groups,” he said.

Caldwell’s office is working with community health centers to support COVID-19 testing for Pacific Islanders, and also wants to hire someone from the Pacific Islander community to join the city’s economic revitalization team and serve as a liaison with Pacific community leaders. He doesn’t have any Pacific Islanders on staff now.

Mayor Kirk Caldwell’s office is publishing messages in multiple languages about COVID-19.

His team published COVID-19 messages in Samoan, Tongan and Marshallese on social media on Friday, borrowing graphics from Los Angeles County.

Caldwell said the delay in sharing translations is because Honolulu doesn’t have a public health department like Los Angeles. Still, he acknowledged that even if action is being taken, it’s not fast enough.

“We should’ve started earlier,” he said. “We are not waiting for the Department of Health anymore.”

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship and its Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published on Civil Beat]