In Milwaukee's poorest ZIP code, fruits and vegetables become powerful weapons for saving young boys

James E. Causey’s reporting on this project was completed with the support of a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism grant.

Other stories in this series include:

I returned to the 53206 neighborhood — and saw some boys turn into men

Want to get involved in a community garden? It's not all weed-pulling.

How a Milwaukee community garden helped turn a struggling boy into 'Lil Obama'

Milwaukee couple make it their mission to give trauma victims the chance to talk and be heard

A reporter shares lessons from a Milwaukee garden trying to save at-risk boys

Nate Collins, 19, left, helps Deonta Williams, 9, prepare to plant a tomato plant on a Saturday in July at "We Got This," a program that focuses on mentorship for black boys in one of Milwaukee's most troubled neighborhoods. (Photo: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

It’s 6:35 a.m. on a humid Saturday in a community garden on Milwaukee’s north side, and a black man is kneeling to inspect the green tomatoes starting to form on a vine.

He’s singing an old Negro spiritual: I am on the battlefield for my Lord. And I promised him that I would serve him till I die.

Andre Lee Ellis spends every day on the battlefield.

It surrounds his home, his garden, his neighborhood. His fight is to save boys growing up in the 53206 ZIP code, which has one of the highest incarceration rates for black men in the nation — and one of the shortest life expectancy rates.

I am on the battlefield for my Lord.

Ellis’ weapons are fruits and vegetables, mentorship and love. And, when called for, a stern demeanor.

His garden, on the corner of North 9th and West Ring streets, has two dozen four-by-six-foot vegetable boxes, which will produce zucchini, lettuce, eggplant, green beans, tomatoes, cantaloupe and blackberries. In the fall, the produce will be given away to area families in need.

It is June 16, the kickoff of the fifth year of the “We Got This” program, which Ellis, 58, runs on a shoestring budget. The program is aimed at boys, ages 12 to 17. They arrive each Saturday to work in the garden, pick up trash in the neighborhood. At the end, they collect a $20 bill for their efforts.

Along the way, they receive support and guidance from adult mentors.

It is 6:55 a.m. The program starts at 8 a.m. sharp.

Ellis takes a seat on a wooden bench and uses his baseball cap — 53206 written on the front — to wipe beads of sweat from his face.

Every summer, there are worries: Will there be enough money? Enough mentors? Will the boys be safe? The volunteers?

For Ellis, the worries continue during the other seasons as well. Two boys and one volunteer were killed since the last harvest.

Andre Lee Ellis is founder of "We Got This." Ellis says, “We can find peace right here in 53206. This is a beautiful place with beautiful people, and we don't have to go to Shorewood or Mequon to find that.” (Photo: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Deaundra Taylor, 15, was shot and killed Nov. 1, 2017. Volunteer Kevin Williams, 32, was shot and killed Jan. 29. In May, Dennis “Booman” King, 15, was beaten, stabbed to death and his body set on fire. It was found May 20 in a vacant house about four blocks from the garden. Mayor Tom Barrett called the homicide "totally senseless."

Ellis was shaken by what he called an "evil act of violence." Weeks later, on the first day of the program, the pain is still sharp.

Now Ellis begins to pray aloud:

“Dear God, I ask that you look out for the young men who will be coming here today to look for guidance," he says. "And keep teaching us how to love each other, for this is how I pray. Amen.”

His hands shake as he stretches his arms and reaches toward the sunny sky.

By 7:27 a.m. there are already 14 boys lined up to get into the garden. The first had arrived at 7:15 a.m. Many are in shorts; a few are in flip flops.

As the clock ticks toward 8 a.m., Ellis yells down the street at a few boys who are walking in the distance.

“Hurry up! You know 8:01 is late!”

Before the youths can set foot in the garden, Ellis requires them to shake his hand and make eye contact. Then he acknowledges them in a positive way. He asks about family members and happenings in the neighborhood. He congratulates one teen who he heard made $80 in a single day cutting grass for his neighbors.

“Man, you are going to be rich if you keep that up,” Ellis says, then adds with a purpose: “Now you know what you need to do? You need to get a banking account, so you can start saving your money for college.”

When a 16-year-old arrives, bandages and scratches on his arms, Ellis asks why he was in a fight.

"No reason."

“Well, where were you that ‘no reason’ is causing you to get jumped on? You are in the wrong place with the wrong people," Ellis replies. "You can’t be coming to the garden beat up, because that is going to have you angry.

"And that is going to make you want to get a weapon and hurt somebody back … and then you are going to end up in prison."

Ellis is often purposefully harsh.

“I try to provide them with the tools to grow," Ellis said, "so they can make that decision not to jump in that (stolen car), and not to pick up that gun, because they need to make those decisions when no one else is around.”

Ellis also notices qualities the kids may not see in themselves.

Two years ago, he met Jalen Green, 12, and told him he sees him with a microphone. Jalen was asked to give a speech at the annual "Tuxedo Walk," a December fundraiser for the garden attended by the boys, mentors and community supporters.

“Little did he know that years earlier, Jalen could not speak in complete sentences because he had a speech disorder,” said Cadence Jackson, Jalen's mother. “But he believed in my son."

Jalen told his story in front of 500 people, and received a standing ovation.

“Before that, I never thought that I could talk in front of people," Jalen said. "He brought something out of me.”

Andre Lee Ellis, founder of "We Got This," gives Nicholas Johnson, 9, a rebuke on a Saturday in June. Ellis is known for his stern approach, but at the same time often tells the boys they are special and he loves them – words he says they don't hear often enough. (Photo: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

In the garden, gang handshakes, cursing and running are forbidden. Boys with sagging jeans are instructed to pull their pants up.

“I don’t want to see your drawers,” Ellis said. “Nobody wants to see that. And the women definitely don’t want to see it.”

On the first morning of the 10-week program, more than 50 boys arrive — a big number considering Ellis doesn't advertise. The number will grow over the summer as more kids find out about the program via word of mouth.

A few of the boys get there just after the 8 a.m. cutoff, and are scolded.

"I’m going to let you slide this week but next week you have to be on time because that’s the rules,” Ellis says.

He knows many will have questions about "Booman," who was a popular figure in the garden the prior summer. Police say he was killed because he allegedly took someone's video game system. Malik M. Terrell, 21, has been charged in the death.

It's not long before a young man asks about what happened.

“Booman was a really good kid and a hard worker," Ellis says. "I miss him.”

"I still can’t believe they killed him like that,” says Marshawn Dixon, 20, who participates in the program. While Dixon is older, Ellis' age restriction for participating is a loose one.

Ellis puts his arm around Dixon and takes him to the side. Dixon wipes away tears before returning to the garden.

For some, this is the first time they have had the opportunity to get those tears out and talk about how they feel, Ellis said.

“This is a place where you can do that.”

The 53206 ZIP code is the city's poorest and most troubled.

Of the 29,000 residents, 45 percent live below the poverty line, which is $25,100 for a family of four. Only 36 percent of working-age males are employed; 66 percent of the homes are headed by black women.

In a state with the highest black male incarceration rate in the nation, 53206 is ground zero, according to Lois Quinn, a former University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee researcher.

In a 2013 report, she wrote the area included nearly 4,000 black men who were in prison or had been, meaning virtually every block had multiple ex-offenders. There is little evidence things have changed in the years since.

Problems scar the area, creating a cycle that echoes from one generation to the next: Being without a job encourages illegal moneymaking activities in order to make ends meet, Quinn said, which increases the risk of incarceration.

"A prison record carries a stigma in the eyes of employers and decreases the probability that an ex-offender will be hired, thus continuing the cycle."

Simply cleaning up a vacant lot can make a difference.

In a study published in July, a group of researchers from Philadelphia found that low-income people living near newly “greened” lots not only felt better about their neighborhoods, they also reported lower levels of stress and depression.

A 2017 study from the University of Chicago found that children from disadvantaged neighborhoods who had a summer job, worked with mentors, and received behavioral training and conflict management reported a 33 percent reduction in violent crime arrests the following year.

What has happened around 9th and Ring?

In December 2011, a month before Ellis moved there, the area was home to the second-highest crime block in the City of Milwaukee. Today, police say it is no longer in the top 50.

From 2014 to 2018, property crime fell 10 percent in a broader area that includes 9th and Ring, statistics show. Still, violent crime increased about 12 percent.

“I know what Andre is doing is working,” said Ald. Milele Coggs, who represents the area.

She told the story of Ellis confronting a man dealing drugs. The man said he was trying to support his family because he couldn’t find a job. Ellis promised that he would find him a job if he stopped dealing drugs.

Ellis got the man a job at an Old Country Buffet restaurant. The man later enrolled in culinary school at Milwaukee Area Technical College.

“Several years ago he was offered a job working at a restaurant in Dubai,” Coggs said. “That’s what I call changing a life for the better, and he does this all the time.”

She and others, though, worry about the size of the need.

Milwaukee has 2,940 vacant lots in its inventory of tax foreclosed properties.

At least one-third of those lots are in 53206.

And there is only one Andre Lee Ellis.

Ellis grew up in the area, the ninth of 14 children. For much of the time, his family lived in the Lapham Park public housing complex at 617 W. Brown St.

His biological father died when his mother was three months pregnant with him. The family struggled to get by.

“You hear a lot of people saying they didn’t know they were poor growing up," he said. "I knew we were poor and I didn’t like it.”

After graduating from Bay View High School in 1977, Ellis spent years working for the Hansberry-Sands Theatre Company in Milwaukee before moving to New York in 1987 to enroll in the Herbert Berghof Studio acting school.

“I’ve always loved the stage because it was an escape for me and I could be and do whatever I wanted,” Ellis said.

After graduating, he worked in theater in Atlanta before returning to Milwaukee to become artistic director at Hansberry-Sands. In 1997, he started Andre Lee Ellis and Company, which put on productions here and throughout the country.

The company put on plays like “Quiet As It’s Kept,” a tribute to the legacy of African-American folk heroes, and “Tellin’ It Like It Tis,” a play he wrote that featured 10 black men sharing stories about their life experiences.

When the theater company was no longer financially viable, Ellis and his wife, Angela, were forced to move from Brewers Hill, a diverse community north of downtown, into a duplex on 9th and Ring in November 2011.

Suddenly, Ellis was living the issues he explored on stage.

Less than a week after moving in, he returned home from a trip to the corner store when six or seven gunshots rang out.

“I paused, and I asked, ‘Did they just shoot me?’” he said.

Ellis was not hit, but when he and his wife went to the front window, there was a black man dead in the street. Soon they spotted children standing around the yellow police tape looking at the covered body before it was taken away.

He felt trapped, because they didn’t have enough money to move.

One morning, while Ellis was sweeping in front of his house, he noticed a drug dealer across the street and crossed over to talk to him.

“He asked me what I needed," Ellis said. "And I told him I needed him not to stand on this corner every day selling drugs.”

When the dealer said his name was Butch, Ellis pulled a piece of paper from his back pocket and turned to his acting skills.

“Oh, you are the one that the police were talking about at the police meeting last night," he said, looking down as if the paper included notes from the meeting. "They are looking at you real close. If I were you, I wouldn’t come around here anymore.”

The paper was blank.

Before long, the drug dealer was gone.

One day, Ellis noticed an empty lot on the corner. A neighborhood kid told him it was supposed to be a garden, but nobody ever did anything with it.

Ellis decided he would.

Soon, he had acquired the lot and a $4,000 grant from the city to buy new box gardens.

Ellis wanted the garden to be a meeting place for the neighborhood. When adults had disputes, he wanted them to be resolved in the garden. Instead of coming to blows, he wanted them to start up the grill, have a burger, and talk it out.

When Ellis told his mother about the homicide on 9th and Ring and how he intended to change the neighborhood, she told him he was home. He was born in a house on 10th and Ring, just a block away.

“I never knew that," he said. "God is good.”

Each summer, dozens of boys participate in the garden program, which completed its fifth year in August. (Photo: Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Ellis created the youth garden program after a mother knocked on his door seeking help for her 11-year-old son, who had been arrested for stealing cars. The boy, Jermaine, had not seen his father in years.

Ellis went to the police station and — in a moment of desperation — told the captain he was starting a program for young people, and Jermaine would be a participant.

He improvised the details: The program would go from 8 a.m. to noon every Saturday and he would pay the boys $5 an hour.

The captain asked what the program was called.

The response: “We Got This.”

On that first day, the following Saturday, Jermaine showed up 45 minutes early. During a break, he told Ellis he “was not as bad as people say I am.” At the end of the day, he left with $20 and was told he could come back the following week.

Later that day, when Ellis and his wife were driving home from an errand, they spotted a sharply-dressed young man dressed all in white. It was Jermaine.

When they stopped, Jermaine told them how he used his money. He got a haircut for $5, spent another $5 to take the bus to the roller rink and back, rented skates with $5 and used the last $5 to get a soda and a hot dog.

The following Saturday, Jermaine showed up at the garden with five other boys.

Within weeks, there were a dozen boys. Then more.

Ellis realized that he was on to something, but needed a way to pay them all.

He posted a picture on Facebook, described what he was doing, and asked friends and followers to contribute. Soon, adults were arriving — offering $5, $20, whatever they could afford, to support the effort. Some started to volunteer.

On most days, the ratio of boys to volunteers is about 15 to 1. Ellis would like to have that number closer to 5 to 1.

"It doesn’t get more grassroots than this," said Ellis, "because the community is supporting these boys and the boys can see it."

In the garden, amid the digging and planting, the watering and weed-pulling, Ellis constantly offers advice.

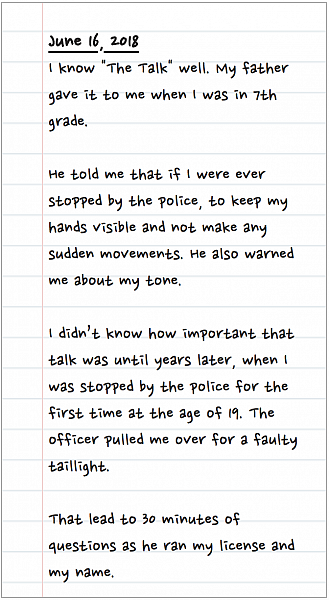

He tells the boys to not let the way people look at them stop them from being nice to each other. And that racism and discrimination can cause people to act out.

“You don’t have to be what the media portrays you to be," he says. "Prove them wrong.”

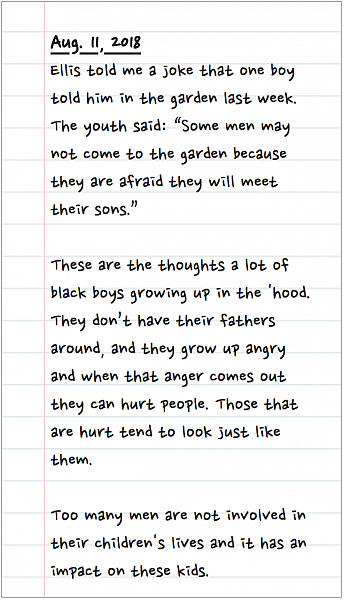

Ellis works mainly with black boys ages 12 to 17 because it’s a critical age when they can either go left or right — especially if they don’t have a father or a positive male figure in their lives steering them in the right direction.

Often, 80 to 90 percent of the boys who come to the garden don't have relationships with their fathers. Many have lost fathers to incarceration.

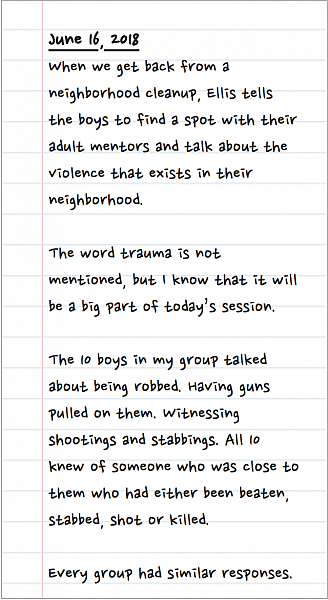

Each week, when the work is done, it is time to talk. The boys and mentors break into smaller groups.

On the third Saturday of the program, the focus is on violence they have witnessed.

One boy describes how a bullet “whizzed by my head” when his neighbors got into a fight.

Another says his cousin was shot and killed outside of their home. The men who shot his cousin then ran into the home looking for any witnesses. He and his mother hid in the basement, terrified, as the men searched the house.

“I keep thinking that they are going to come back and kill me one day,” he says.

When asked who they talk to, one says, simply, "God."

In Wisconsin, 88,000 children have had at least one parent in prison at some point in their lives, according to a 2016 report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, called “A Shared Sentence.”

That group includes more than 40,000 African-American children, many of them in Milwaukee, said Reggie Jackson, head griot, or storyteller, at America’s Black Holocaust Museum, who studies disadvantaged communities and uses that information to hold community discussions.

“Those parents are absent from their children’s lives for years,” he said.

Incarceration has played a critical role in the life of Devin Bell, 17, who lives on North 11th St. and West Keefe Ave. — three blocks from the garden.

“I will be the first Bell to be of legal age to not have contact with the police whatsoever,” he said, and broke it down: “My father has felonies. All five of my uncles are in prison. Two are serving 25 to life the rest are doing bits of 25 years.

“Those are the men who could have been a part of my support system."

Ellis often tells the boys that he may not be their “birth dad," but he is their "Earth Dad."

Bell has been coming to the garden for four years. For him, it's about more than the $20 weekly payment.

“I just like being around positive men who are on a positive level," he said. "You get tired of being around people who are just getting in trouble, stealing cars and hurting people.”

Bell, a senior at Pulaski High School, has seen people jumped, stabbed and killed. He doesn't like to talk about it, doesn't like to think about it.

"You can just come here and chill," he said of the garden. "Sometimes I just come out here and sit by myself when things get too difficult.”

Speakers at the Saturday sessions show the youth a slice of what is possible.

One Saturday, Muhibb Dyer, a nationally known spoken word artist and community activist who grew up on North 12th and West Ring streets, stands in front of the boys, holding his 3-year-old daughter, Mahdiya.

He tells of a childhood friend who is serving 60 years in prison for selling cocaine. He tells of another who is serving 25 years for a bank robbery.

He tells how his own godson was shot to death in 2006. He was 16.

Dyer, 43, tells the boys to think about what they want.

“When you want 'hood respect,' you don’t give a damn how you make your money," he says. "You want to make your money even if you must destroy everything around you. You don’t care about the families you are tearing apart because as long as you make your money, you’re straight.”

He sets Mahdiya down, and pulls a diploma from his backpack: the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2000. That degree in educational policies and community studies took more than 1,000 hours of study. It represents "community respect."

“When you want world respect, you build yourself," Dyer says. "You get educated and you decide you are going to make your money giving hope. You are going to make your money giving dreams. You are going to make your money making your 'hood better than how you received it.”

When he finishes, the circle of boys stands and applauds.

Even after five summers, the program operates week to week financially.

Some Saturdays, Ellis does not know if he'll have enough money to pay the 60 to 100 boys until a Facebook message is sent and benefactors arrive.

It costs about $4,000 a week. Ellis is proud of never having missed a payment for a boy. A board of directors is working to get non-profit status for "We Got This."

Ellis does not draw a salary or have another job — the boys of the neighborhood are his calling. Sometimes he is paid for speaking engagements, but the main source of household income is his wife's paycheck from Pick 'n Save.

One member of the We Got This board is Sandy Botcher, 55, a Mequon resident who each Saturday brings about six dozen cookies for the boys to eat during their break. She started volunteering in the garden four years ago after she heard the story of how Ellis helped Jermaine.

“I was on my own journey to understanding what was really going on in Milwaukee,” said Botcher, who is white. "I don’t feel that I have any racial bias, but there are things that you don’t know, and they shape what you think.

“I needed to know what it was like to be these young men."

Her goal is to make sure “We Got This” becomes sustainable.

“Right now, he’s muscling it all," she said of Ellis. "We need to let him be where he’s best and that’s working with the youth.”

One Saturday in mid-July, as the boys were about to get started with their cleanup, a car speeds past the garden. The 16-year-old driver: Jermaine, the boy Ellis helped five years ago.

The two had developed a bond, but Jermaine had a wild streak that left Ellis worried about him being hurt, or hurting someone else.

“He ain’t going to make it,” Ellis says. "Sometimes we have a death wish. We don’t want to kill ourselves, but wish someone else would do it.”

As Ellis tells the boys about what was in store that day, the car — a stolen Nissan — speeds past again. Some of the boys seem impressed.

“Don’t be distracted by the loud noises in life," Ellis says. "They only come to throw you off. If you ignore the loud noises like that of life, they will disappear.”

The car pulls up and Jermaine drops three boys off. The youngest, 12, is wearing an electronic monitoring bracelet nearly as big as his foot.

Ellis allows the 12-year-old to stay to help serve lunch. The other two boys sit on the stairs of the grocery store across the street. Later, when the work is over, one of the boys snatches a $20 bill from one of those who worked all morning to earn it.

The three run away and other boys chase them.

Soon, the three are back standing before Ellis, each denying their involvement. Ellis is shaking with anger and disbelief.

“I know one thing: We are going to get this $20 back,” Ellis says. “Now who took it?”

The boy with the ankle bracelet starts crying and admits he was involved. The oldest boy eventually takes the money from his pocket and returns it.

Ellis asks the boy with the ankle bracelet why he would grab someone's money in front of so many witnesses.

The response: "I don't know."

There is disagreement among the group — mentors and kids alike — about what should happen to the three. Some say they should be banished from the garden.

For Ellis, such situations are a difficult calculus.

How do you balance rules with second chances? What message does your decision send to those who followed the rules — and those who broke them?

But, mostly: How can you save a kid, if he's not there?

“Each kid in this equation is valuable and can learn from their mistakes," he said later. "We need to make them understand that their actions have consequences and when they harm their brothers it has lasting effects.”

The next day, two of the boys knocked on Ellis’ door to apologize.

In this case, his calculation was right.

“I’d rather go to a graduation instead of a funeral,” he said.

How 'We Got This' was started

One Saturday in mid-July, as the boys were about to get started with their cleanup, a car speeds past the garden. The 16-year-old driver: Jermaine, the boy Ellis helped five years ago.

The two had developed a bond, but Jermaine had a wild streak that left Ellis worried about him being hurt, or hurting someone else.

“He ain’t going to make it,” Ellis says. "Sometimes we have a death wish. We don’t want to kill ourselves, but wish someone else would do it.”

As Ellis tells the boys about what was in store that day, the car — a stolen Nissan — speeds past again. Some of the boys seem impressed.

“Don’t be distracted by the loud noises in life," Ellis says. "They only come to throw you off. If you ignore the loud noises like that of life, they will disappear.”

The car pulls up and Jermaine drops three boys off. The youngest, 12, is wearing an electronic monitoring bracelet nearly as big as his foot.

Ellis allows the 12-year-old to stay to help serve lunch. The other two boys sit on the stairs of the grocery store across the street. Later, when the work is over, one of the boys snatches a $20 bill from one of those who worked all morning to earn it.

The three run away and other boys chase them.

Soon, the three are back standing before Ellis, each denying their involvement. Ellis is shaking with anger and disbelief.

“I know one thing: We are going to get this $20 back,” Ellis says. “Now who took it?”

The boy with the ankle bracelet starts crying and admits he was involved. The oldest boy eventually takes the money from his pocket and returns it.

Ellis asks the boy with the ankle bracelet why he would grab someone's money in front of so many witnesses.

The response: "I don't know."

There is disagreement among the group — mentors and kids alike — about what should happen to the three. Some say they should be banished from the garden.

For Ellis, such situations are a difficult calculus.

How do you balance rules with second chances? What message does your decision send to those who followed the rules — and those who broke them?

But, mostly: How can you save a kid, if he's not there?

“Each kid in this equation is valuable and can learn from their mistakes," he said later. "We need to make them understand that their actions have consequences and when they harm their brothers it has lasting effects.”

The next day, two of the boys knocked on Ellis’ door to apologize.

In this case, his calculation was right.

“I’d rather go to a graduation instead of a funeral,” he said.

On the Sunday before the final garden session, Ellis holds a "Salad Festival" to raise money and highlight the fruits and vegetables his crew has grown.

The garden beds are filled with ripe tomatoes, zucchini and cantaloupe, with rows of basil and mint. Several kids eat blackberries and strawberries straight from the bush.

Ellis is proud of the boys and, the day before, had told them they were the best group of men he had ever worked with. He had been hard on them, he said, because he wanted them to be successful.

The Salad Festival is meant to be a fundraiser, but Ellis gave out dozens of free tickets. There is a buffet line of salads, chicken wings from a grill, a cooking demonstration from Ellis.

Some who arrive don't have tickets at all — they are folks who gravitate to the garden because, in the words of Ellis, they are "in need." One older man stops by most Saturdays, filling a plate for himself once the boys are fed. No one questions him.

At the end of the event, as volunteers clean up the garden, there are loud gunshots in the distance.

Ellis recognizes the particular sound.

It sounds like death.

Soon, his cellphone rings. The voice on the other end: "Mr. Andre, Erik is dead and they shot the baby boy, too."

Video: Garden project mentors African-American boys

The man who was killed was Erik Williams, 28, a volunteer for the program. He was trying to shield his 4-year-old son, Erik Demetrious Williams, Jr., known as “Doobie,” but the boy was struck four times and taken to the hospital.

Eight months earlier, 32-year-old Kevin Williams — Erik's brother — was shot and killed at 10th and Ring. A cluster of stuffed animals, deflated balloons, and artificial carnations remain wrapped to a telephone pole as a makeshift memorial.

On Monday morning, his 58th birthday, Ellis writes this on his Facebook page:

"I'm hurting like a father who just lost another Son. Less than 8 months ago we all pitched in to bury his brother Kevin and less the 2-years-ago we helped bury his Mother. Erik always expressed how grateful he was.

"So sorry that homicide no.12 (of the month of August) happens to be one our sons, a real close Son."

The post asks for support and prayers. For Williams and little Doobie, for the neighborhood, for strength, for peace.

"As I close this note 6 loud gunshots just rang out," it concludes. "Yet I have hope and I shall trust God more."

At the funeral, Ellis takes the microphone and addresses the crowd, remembering how Erik Williams always put his children first.

“He loved his kids and they were with him until his last breath."

Ellis looks at the silver casket, where Williams is dressed in a red shirt. Ellis promises he would be there for his boys until the day he died.

Angela Ellis worries about her husband doing too much.

Ellis is diabetic and has been hospitalized several times this year, yet he didn't take any Saturdays off to rest. He pushed himself to raise enough money so the mentors would not have to pay to attend the annual "Tuxedo Walk," usually held in December, but fell short and the event was cancelled.

Angela Ellis said people don't understand the toll of all the late-night phone calls, often requests for help solving family disputes. They don’t hear the knocks on the door from people needing help — not just families of the boys, others in the neighborhood. They don't know how personally he takes things.

That week alone, Ellis attended five funerals.

At the Erik Williams funeral, Ellis consoles several young men. Outside, he tells one young man to either tuck his shirt in his pants, or to take it out completely.

“You can’t be half tucked," he says. "Make a choice.”

The shooting of Erik Williams rattled Ellis.

A few days later, he was working in the garden when Janice Williams, 56, walked up. Erik Williams was her nephew. And a grandson, 15, had been there when he and Doobie were shot. The teen was grazed by a bullet.

She had lived in the neighborhood, and knew the impact the garden had on the area. She had been at the Salad Festival and had just gotten home when she heard the gunfire, opened her door and saw her nephew on the ground in the distance.

She ran down to the shooting scene and saw Erik crawling towards his son.

“He told me, ‘Auntie, just get Doobie. Auntie, just get Doobie,’” she said in an interview. “Then he passed on. Now every time I look down there I’m seeing that.”

While Williams worries about her own mental health, she told Ellis she mostly worries about her grandson.

“He said he’s OK," she said. "But I know my grandson and I know he’s not.”

Ellis promised he would stop by her house. He promised he would continue helping.

“We will get through this," he said. "It won’t be easy, but we all will get through this.”

**

[This story was originally published by Journal Sentinel.]