Part 1: Ashley’s foster home seemed perfect. It held a dark secret.

This is Part 1 of a five-part series was produced as a project for the 2017 National Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Becoming a pawn in the culture war, Ashley hides her abuse from the world

Ashley reveals her abuse and loses everyone she loves

Scarred and abandoned once again, Ashley’s rage takes control

Ashley finds the freedom to fall — and to discover her destiny

Ashley's biological mother Kim Guiden stands in front of her home in Anderson, Indiana, in 2017. (Mykal McEldowney/IndyStar)

Twenty-one years ago, a little girl named Ashley disappeared into the center of a political controversy.

The public never knew the 8-year-old’s name. They never saw her face. Never heard her voice.

But she became a symbol when a gay man sought to adopt her. On one side, people viewed Ashley as a vulnerable child going to a loving home. On the other, people feared her moral well-being was in danger.

The debate captured the state’s attention and spurred rallies, protests and legislation. Less than a year later, Ashley would be unwillingly thrust back into the spotlight.

Each time, when tempers cooled and the public’s attention shifted, the little girl would be left to deal with the aftermath.

All she wanted was a family. A place where she belonged.

Instead, Ashley would be exploited, abused and, ultimately, abandoned by people who said they cared about her. And her invisible wounds would persist for decades.

This is Ashley’s story. It’s a tale describing what happened before and after a political circus came and went. It’s the complex truth behind the easy answers everyone wanted to promote for their own ends. It follows an irrepressible girl whose quest for peace spans three decades. It’s the story of a search for control and freedom that leads her to the streets and the discovery that the worst trauma is the kind you do to yourself.

Her story begins five years earlier, when authorities knocked on the door of her mother’s frigid duplex.

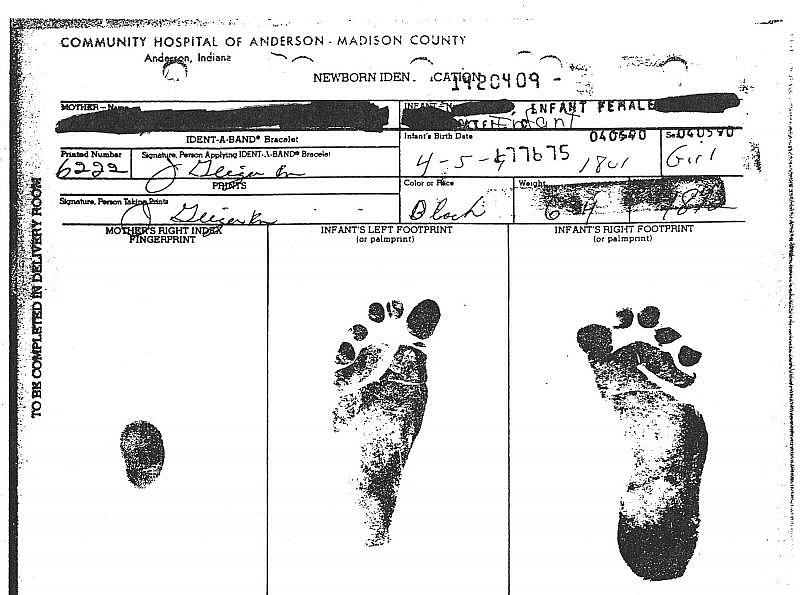

Ashley's baby feet after birth. (MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR)

At 2, Ashley is taken away

Ashley doesn’t remember the first time the strangers carried her away. But her mother does.

At 18, Kim Guiden was virtually on her own with two young children, 2-year-old Ashley and 2-week-old Dashon. They slept together on a mattress on the living room floor in a small duplex in the industrial city of Anderson.

When temperatures in March 1993 dropped low overnight, Kim cranked an electric hot plate to the highest setting to keep warm.

She rigged a blanket to separate the living room from the rest of the unheated duplex. Those areas were so cold that Kim could see her breath.

She called a relative to ask to borrow a kerosene heater.

When a child services caseworker knocked at her door, Kim guessed that relative had reported her to authorities. And, frankly, it ticked her off.

There’s nothing more frustrating, Kim would remember decades later, than people turning you in when you’re asking for help.

She yanked open the door.

Family case manager Dianna Cole inspected the duplex, documenting what she saw. It had no heat, no water, no refrigerator and little food. No clothes for the kids, no diapers. Feces sat in the toilet, debris in the sink. The hot plate glowed beside the mattress, providing a wisp of warmth.

Kim said Ashley’s father, 22-year-old Alison Johnson, paid the rent and electric bill, but she didn’t have enough money for gas.

Cole suggested a parent aide program.

Kim bristled.

This was the fourth child neglect report made about her since Ashley was born less than three years earlier.

Kim insisted on her independence. She had dropped out of school. She was unemployed and received food assistance for the children. Yet she refused to apply for further funding for food, clothing or shelter. Kim didn’t want anything to do with Supplemental Security Income. That program, she said, was for crazy people.

I don’t want or need your help, Kim said. I’m sick of seeing your face.

There’s an easy way and a hard way, Cole told Kim. One way or another, the government was going to help Kim and her children.

As they argued, 2-year-old Ashley ventured over to the kitchen doorway where the blanket hung. She was on her way to go toward the bathroom. Kim screamed to keep Ashley from leaving the room. The little girl retreated to the edge of the mattress. She held herself, crying.

Cole left. Later, she returned with Anderson police.

Kim didn’t know what to do.

“My first reaction was just to take my kids and go and just run,” Kim recalled years later. “But there would’ve been nowhere to go.”

Officials removed Ashley and Dashon.

“Mommy!” Ashley sobbed as she was pulled away. “Mommy! Mommy!”

Cole had ensured their safety. Or so she thought.

In search of a home

Deciding whether to remove a child from a home can be one of the most difficult choices a child welfare official makes.

The child welfare system has changed since Ashley’s removal in 1993, but it continues to operate on the same principles. Parental rights are weighed against child safety. Keeping families together is a priority, provided the children are safe. And minimizing trauma to children is of utmost importance.

It is a system governed by checks and balances. Kim and Alison tried to get the children back. Kim briefly regained custody before the kids were removed again. The young parents attended most of their court-ordered visits. But they were overwhelmed.

During one visit, Kim couldn’t read a baby food jar to determine whether she had fed Dashon peas or green beans. One evaluator said Kim couldn’t name a day of the week, didn’t know the name of the president and couldn’t do simple math, such as subtracting three from a number.

Kim Guiden gave birth to Ashley in Anderson, Indiana, after becoming pregnant at the age of 14. (MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR)

Yeah, six. Five boys. Yeah, that's what they told me, I got a football team, and a cheerleader. But just because they got taken away from me, that don't mean I don't love 'em.

-Kim Guiden

Kim had been drinking more than a six pack a day since she was 13. She guzzled beer throughout her second pregnancy to the point of passing out.

In 1995, Anderson police arrested Kim for attacking Alison with a hammer. It wasn't her first arrest.

Kim was caught in an endless cycle. When things got difficult, she said, she drank. When she drank, she grew angry and violent. “I would get mad at everybody,” Kim recalled. “When I get to drinking and stuff, I get to taking it out on people.”

Alison told IndyStar their ages were to blame. “We were just young parents, that’s all,” he recalled years later. “We tried everything we could do.”

Authorities decided to terminate Kim’s parental rights to Ashley, Dashon and two other sons. Alison and another man lost their parental rights, too.

Settling into a new home

The second time Ashley was removed from Kim's home in 1993, she was placed with Sandy and Earl “Butch” Kimmerling. Her brother went to a different foster home.

Ashley's life with her foster parents was a whirl of toys and trips, art and dance lessons, singing and worshipping God.

Butch, 46, worked for the Indiana Department of Transportation. Sandy, 51, drove a school bus. They attended church Wednesdays and Sundays and surrounded themselves with evidence of their faith.

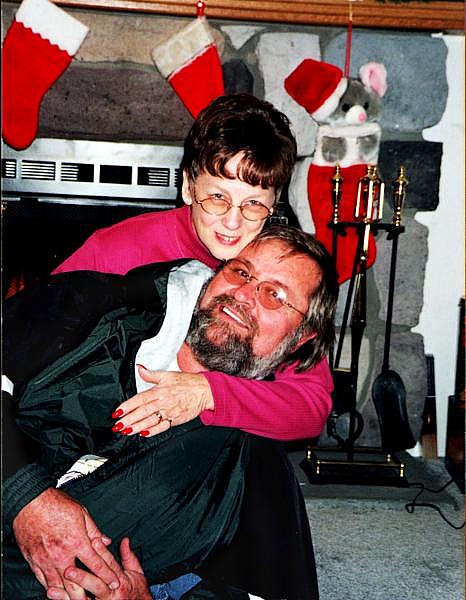

Earl "Butch" Kimmerling and his wife, Sandy hug for a picture from Christmas 1998.

Their door knocker greeted visitors with “Welcome in the name of Christ.” Their ranch-style brick home in Anderson, with its sprawling front yard, was decorated with pictures of Jesus. Butch kept a small studio there, where he wrote and recorded Christian music.

Their blended family included four children and five grandchildren, none of whom lived with them. And Butch and Sandy had cared for 48 children since becoming foster parents in 1991.

When 3-year-old Ashley arrived, the Kimmerlings settled her into her own bedroom. She and Sandy decorated it together — splashes of white, pink and purple, with Barbie wallpaper and Barbie pillowcases, blankets and sheets on her bunk bed.

Butch and Sandy bought Ashley gobs of toys. They enrolled her in tap and acrobatics classes. They took her to Disney World.

Ashley spent most of her time with Butch. He helped Ashley with her homework. They shared a love of music and often sang gospel songs together.

Like many young kids, Ashley could be stubborn and demanding. But overall, child welfare workers reported, the little girl was “darling, cheerful and has a great personality.” She “wins the heart of everyone around her.”

She lived with Butch and Sandy for years.

Ashley loved it there, but the Kimmerlings did not want to adopt.

Child welfare officials connected Ashley to a therapist who said the little girl couldn’t “relax and ‘be a kid’ because she doesn’t know where home will be.”

The uncertainty was one of many issues that would weigh on her.

“Here’s the thing about children that are in foster care,” Ashley explained years later. “We might not remember who our parents are or remember what they look like, but we still dream about them coming to get us. And that’s just the whole trauma aspect of it for us kids. We’re always waiting and thinking, making up scenarios.”

Feeling out of place

Ashley, who is black, never forgot that she looked and acted different from her all-white foster family.

She said the Kimmerlings forced her to change into their vision of a little girl. They were particular about how Ashley wore her hair and clothes. Ashley said she was a tomboy, but they made her wear “girlie” clothes, such as tank tops.

One day, Sandy wanted to paint Ashley’s nails gold. Ashley didn’t like nail polish. “I just bawled my eyes out,” Ashley recalled.

The Kimmerlings also spent a lot of time correcting Ashley’s speech and behavior.

A mistake in table manners? Go stand in the corner.

Using “ain’t” instead of “aren’t”? Go stand in the corner.

Biting the side of her mouth? Go stand in the corner.

When the Kimmerlings took her to visit their children and grandchildren, Ashley remembers being blamed for things the grandchildren did. She remembers having to clean up after the other kids.

When Ashley got in trouble, Sandy warned the little girl she would end up just like her mother. Ashley had begun to forget her mother’s face. She believed Kim was a bad person. She thought that meant she would be bad, too.

Ashley felt she didn’t belong. At least not with the Kimmerlings.

“You know,” she explained years later. “Just extra.”

‘It won’t let me remember’

One day, while Sandy was gone, Ashley cuddled against Butch in an oversized brown recliner in front of the TV. The little girl draped her arm over her foster father’s big, round belly.

They had sat this way many times before. Maybe it was a Wednesday. Maybe it was a day Sandy was at church. Ashley doesn’t remember.

“My subconscious, I’m scared that, you know, it won’t let me remember,” Ashley said years later. “Because if I remember, it’s no telling what I would try to go do to him.”

But she does remember that on this day, Butch captured her hand and pushed it lower. Past his belly and onto his crotch.

It was something he would do again and again. It happened most often in Ashley’s bedroom, when Butch woke her up for school, when Sandy was already at her job driving a school bus.

When Ashley touched her foster father’s penis it would get wet and the wet stuff would get on her bed. He touched her, too.

At first, Ashley said she didn’t realize that what was happening was abuse. She was a kid. She didn’t know it was wrong. Butch never threatened her, never warned her not to tell anyone. Instead, he plied her with snacks and ice cream.

‘Open about the gay issue’

In 1997, child welfare officials looked for a permanent home for Ashley and her three brothers, who lived with a different foster family. After a year, officials found a man willing to adopt.

An Indianapolis man named Craig Peterson pursued adoption of Ashley and her brothers after seeing them in the “My Forever Family” picture book of foster children available for adoption and in a June 7, 1998, Indianapolis Star article. He applied as a single parent, though he was in a long-term relationship with a man named Richard Weaver.

Butch and Sandy joined child welfare officials at an Aug. 25, 1998, meeting where a committee would decide whether the two men should be allowed to adopt the four siblings.

During the meeting, Janice Heiss, a family case manager, noted that Craig and Richard seemed committed to being partners in the adoption. They had been together for more than three years. They were active in church. They had some child-rearing experience. They were “open about the gay issue and will be with the kids.”

Butch was incensed by Craig and Richard’s lifestyle. He said Ashley wouldn’t like it. He urged the committee to reject Craig’s petition.

Butch issued a warning: “Ashley will not be satisfied with this family.”

He said Ashley didn’t want to live with her brothers and preferred to be an only child.

“She will get even,” he warned.

Sandy said she was concerned about the gay parents. Ashley would not have a woman around.

Lonny Hunter, the children’s family case manager since 1993, couldn’t attend the meeting. So he asked another worker to convey his opinion. Hunter believed the children had enough problems without being teased or harassed for having gay parents. And Ashley had told him her one wish was to have a “brown mother.”

Lonny Hunter, Ashley's family case manager (MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR)

We treat our children like used cars.

-Lonny Hunter

“How can I promise her a brown mommy and go in and say, ‘Here's white daddy?’” Hunter told IndyStar years later. “You know? It just wasn't what Ashley herself was requesting. And I was respectful of that.”

Ashley remembers saying that, but she also remembers Hunter saying it to her.

“It was part of how I felt but also what I had been told,” she said years later.

No one else wanted Ashley and her brothers. Nine other families had backed out after reading about the siblings’ diagnoses. All four children had some level of fetal alcohol syndrome, which can severely affect a child’s physical and intellectual development.

LaShone, 3, struggled with behavior problems.

Miguel, 4, battled rage and anger.

Dashon, 5, had a high palate and severe speech problems.

Ashley, 8, had partial fetal alcohol syndrome. She was doing well. She got good grades. She loved art and acrobatics. But she was stubborn. A bit of a loner. She argued with Butch but not with Sandy.

When the discussion was over, the Kimmerlings stepped out of the room. The people left took a vote.

If anything happens to Ashley...

Hunter’s “no” vote was read into the record. Another person voted “no,” saying her personal beliefs would not allow her to vote for a gay family. One person abstained. Everyone else said yes.

It was official: Craig and Richard were going to be parents. Ashley and her brothers were going to have their forever home.

Heiss and a children’s advocate walked outside to tell the Kimmerlings. The foster parents appeared devastated.

Review your Bibles, the Kimmerlings said.

Sandy began to cry. She told them she had been sexually abused as a child.

If anything happens to Ashley, Sandy warned, you will pay.

The Kimmerlings weren’t going away without a fight.

[This article was originally published by The Indianapolis Star]