Special Report: Hollister School District mirrors method to provide social-emotional support to students

This is the second in a three-part series about the social-emotional health of students in Hollister. This article was produced by Noe Magana as a project for the Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 California Fellowship.

Read the other parts of this series here:

Part One: BL Special Report: HSD struggles with high suspension rates

Part Three: BL Special Report: Students falling through the cracks

Students walking to school. File photo.

Accustomed to wearing khaki pants and a white polo shirt for his school-mandated uniform, 14-year-old Elias Leon didn’t think too much of it when he first stepped into Marguerite Maze Middle School in that outfit in 2014.

For him, it was odd the other students weren’t in uniform. But for the other students and teachers, he was the one standing out.

“Right when I got there, the first day the kids were looking at me like I was a cholo, like I was a gangster coming from San Jose,” Leon said, who was in eighth grade at the time.

Having experienced homelessness, having been around drug abuse and jumping from school to school for most of his life, Leon didn’t attach much importance to his academics. Instead, he said he talked back to teachers, goofed off and tried to be funny.

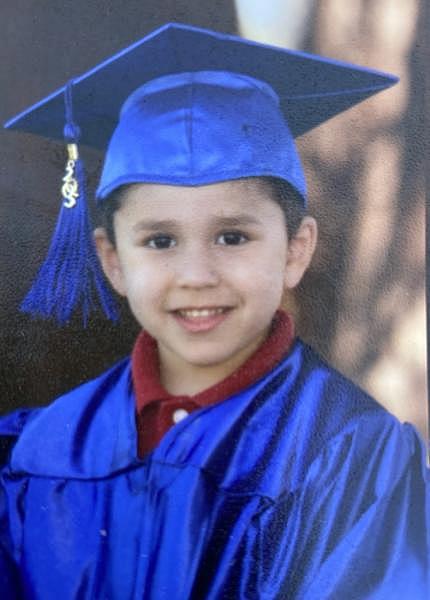

Elias Leon. Photo provided by Shawna Padilla.

Before the end of that school year, Leon was transferred to Santa Ana Opportunity School because of his low academic performance—one of four schools in the county for students referred from primary school districts for being “unsuccessful,” according to a state-mandated accountability report.

That same goofing off behavior landed Leon a suspension in ninth grade, though he doesn’t remember what exactly he did to earn it.

Before the end of 10th grade, Leon had had enough and decided to drop out.

“Something in my head just told me that I really didn’t want to go to these schools anymore and I just wanted to work,” Leon said.

Along with Leon in the 2016-17 school year, 32 other students in grades seven through 12 in San Benito County dropped out of school. Of students who dropped out of school that year, 82% were Hispanic. Comparatively, only 71.2% of students in that grade were Hispanic.

Following his decision to drop out, Leon then enrolled and later left the Job Corps job training program before landing under-the-table work in moving and shipping and handling.

In an effort to help students like Leon who disengage from school and typically exhibit disruptive behavior that results in suspensions, the Hollister School District adopted a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) for its over 6,000 students.

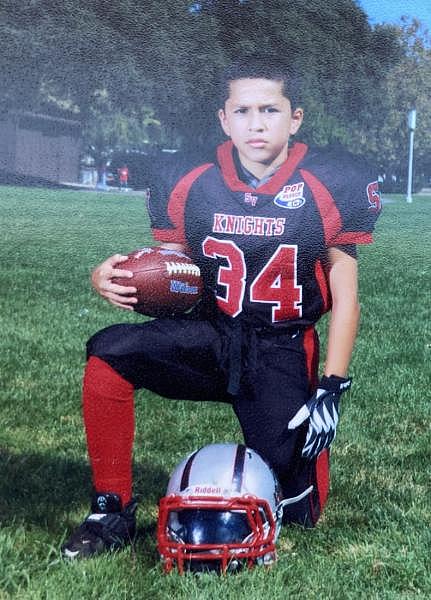

Elias Leon. Photo provided by Shawna Padilla.

According to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, youth act out for a variety of reasons, including anxiety, depression, chronic stress or because of a disruptive behavior disorder. The cause of disruptive behavior disorder is not known, but is believed to spring from various factors such as witnessing domestic violence, substance abuse and experiencing neglect.

It is estimated that 6.1% of American children have a disruptive behavior disorder. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, disruptive behavior disorder usually starts before the age of eight and no later than age 12.

For the 2020-21 school year, Hollister School District Superintendent Diego Ochoa, who was hired in 2019, told BenitoLink he plans to hire a district social worker and five San Jose State University graduate counselor interns to work with students. Ochoa said the district also plans to hire six additional licensed clinical social workers or licensed marriage and family therapists the following school year, with the ultimate goal of having a social worker or school counselor for each of the 11 school sites.

“The nice thing about those positions is they are able to always take on interns, so the district will always have a roster of counselor interns who can give counselling support to kids who are not at an urgent level, but need some mentorship and what we would call tier 2 support,” Ochoa said.

He said eventually a five-tiered system of support would be put in place to address different levels of need for students who exhibit behavior problems, mirroring the San Benito High School District model.

The first tier consists of classroom teachers who can provide emotional support on a daily basis. The teacher would then refer students who need additional support to the second tier, consisting of the principal and vice principal. California passed the “willful defiance” law—SB 419—in 2019 in an effort to lower suspensions for student actions teachers deemed inappropriate.

If administrators determine the student needs additional emotional support, students would be seen by the counseling intern. The social worker would be the final tier and would serve the students most in need.

“If the child really needs intense clinical therapy, that social worker can easily refer [students] to San Benito County mental health,” Ochoa said.

Diego Ochoa speaks to the public during a 2019 board meeting at which he was introduced as the new superintendent. Photo by John Chadwell.

The county’s Behavioral Health Department was consulted for referral data. However, Assistant Director Rachel White said the department denied BenitoLink’s request to know how many referrals the unit received from the school districts.

Following a public records request, the county revealed that in the 2019-20 school year, 159 children between the ages of five and 15 were referred to the San Benito County Behavioral Health. Maxe Cendaña with the Behavioral Health Department said it doesn’t keep track of reasons for referral or who referred them.

Marilyn Shepherd, a consultant who delivered a report on HSD’s special education department in 2019, does not think Ochoa’s plan for interns is the answer. One of the challenges with using interns, she said, is that they are young and lack expertise in ways of addressing the needs of special education students.

Shepherd, who noted that what HSD is experiencing is a statewide problem, said hiring additional staff to address behavioral issues is one approach. But what a lot of districts throughout California are doing is training general education teachers and staff to deal with not only students with behavioral issues, but also those with special needs.

“That’s what was said in my report repeatedly, [it] was professional development, training everybody on how to address the issues at an early stage so they don’t have to be referred to special ed,” Shepherd said.

In the 2019-20 school year, the Hollister School District added five additional psychologists serving a population of 6,154 students in 11 schools which brought the total number to nine psychologists, four of whom speak Spanish.

Shepherd said that a couple of years ago she trained HSD staff to assess a student’s needs and develop a behavior plan using the Insights to Behavior program.

Ochoa said the district does not use Insights to Behavior, but provides a variety of mandatory and voluntary professional development for staff. He said QBS is mandatory for special education staff and voluntary for general education staff; Capturing Kids Hearts is mandatory for all staff; and Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (PBIS) is mandatory for all middle school staff.

The district is addressing its high suspension rate, Ochoa said, specifically in its two middle schools through staff training and adding academic support through Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) and Construction Meaning programs.

Prior to COVID-19, the district began addressing middle school overcrowding in an attempt to reduce suspension rates.

“High class sizes in primary grades are causing concern related to the difficulty in providing individualized support,” the district’s 2019-20 state-mandated Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) states. It also notes that there are “minimal” after school and summer school options for students.

The California Department of Education data provides average class sizes for the Hollister School District by subject. Excluding physical education classes, multiple-subject classes have the highest average class sizes with 37.3 students, while art is the lowest with 18.2.

Maze Marguerite had a suspension rate of 16.4% and Rancho San Justo was 11.1% for students in grades six through eight in the 2018-19 school year. Comparable statewide percentages were not available. However, the state showed drastically lower suspension figures for students in grades four through six at 2.9% and students in grades seven and eight at 6.7%.

“The district has also determined that Rancho San Justo and Marguerite Maze School were overcrowded and has transitioned three additional schools to serve cohorts of 30 upper grade students in each year,” Ochoa said. “In 2019-20, we have added sixth grade classes at Ladd Lane, Sunnyslope and Cerra Vista. Doing so has made Rancho San Justo and Marguerite Maze School smaller, and we believe more likely to result in stronger peer-to-peer relationships.”

The multi-tiered support system along with staff training may have had an immediate impact on San Benito High School’s suspension rate, which fell from 5% to 4.1% since its introduction three years ago. As part of its support system, San Benito High School is implementing its wellness center, which will include a team of counselors, administrators, social workers, and social worker interns within the same area of the campus.

The high school is also implementing PBIS, which focuses on reinforcing student positive behaviors. It does this by recognizing students for academic or personal achievements. SBHS superintendent Shawn Tennenbaum said staff also recognize students who might need extra motivation. Those students then participate in student-teacher luncheons, which have since stopped because of school closures as a result of COVID-19.

Similar to its overall school suspension rate, SBHS’s Hispanic student suspension rate has gradually decreased from 6.2% to 4.7% since the 2014-15 school year. However, data shows Hispanic students are disproportionately represented in the suspensions with each passing year.

In the 2018-19 school year (taking into account enrollment increased 2.2 percentage points), the percentage of suspended students who were Hispanic jumped from 73.7% to 84.4%.

But in 2019-20, “when we look at our Latino student suspension rate, we have a notable decrease in the percentage of their suspensions, compared to their percentage of total enrollment,” said SBHS Principal Adrian Ramirez. “Our focus and area of growth continues to be within our male Latino student population.”

As of Oct. 28, the California Department of Education has not published the state’s 2019-20 suspension statistics.

SBHS’s efforts to keep students engaged in school and receive social-emotional support despite displaying behavioral issues has resulted in 78% in-house suspension, where students serve their suspension on school grounds rather than at home.

However, the pandemic could erase this recent progress, especially for students who lack internet access. One study suggested that before the beginning of the school year, teachers would encounter a wider achievement gap in their classes—students who fared well during distance learning, and those who did not.

“Thus, in preparing for the fall 2020, educators will likely need to consider ways to support students who are academically behind and further differentiate instruction,” the study said.

A group of San Benito High School students is having difficulty with distance learning. According to data presented on Sept. 22 to the San Benito High School District Board of Trustees, 26.7% of students have an overall grade of F, while 10.8% have a D.

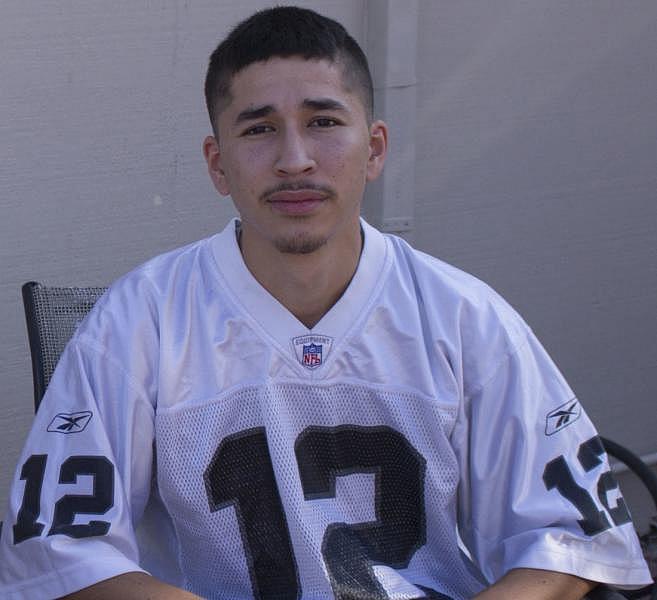

Elias Leon, who is now 20 years old, said it would have taken a genuine effort from someone to get him back on track in school because he didn’t trust just anybody.

Elias Leon. Photo by Noe Magaña.

“Just some nice person that I could talk to and understand,” Leon said.

Shawna Padilla, Leon’s mother, said Leon never wanted to go to counseling but looked forward to meetings with the mentor assigned to him in Santa Clara.

Leon said he never felt like he could talk to a counselor or teacher because it was always in a formal setting and felt like they always asked the same questions so he just gave the answers he thought they wanted to hear.

“I would just get the question done with and they would be ‘all right, okay, you can go back now,” Leon said.

On the other hand, he said he really could open up with his mentor.

“When I was a kid I had a lot of anger issues and s**t so we would just talk about my anger and stuff and try to get through that and tried to help me,” Leon said, adding they also talked about school and his plans for life.

Padilla said the mentors looked just like Elias—young and Latino—which enabled her son to relate with them. The mentor program ended for Leon when he moved to San Benito County.

[This article was originally published by Benito Link.]