Educators Use Poetry to Help Kids Talk About Trauma

This story was produced as a project for the 2019 California Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Trauma Can Drastically Impact School Attendance

Paradise Counselors Address High Rates of PTSD Among Students

Housing Insecurity is Taking a Toll on Youth Health

October 2017 Wildfires are Affecting Crucial Health Programs

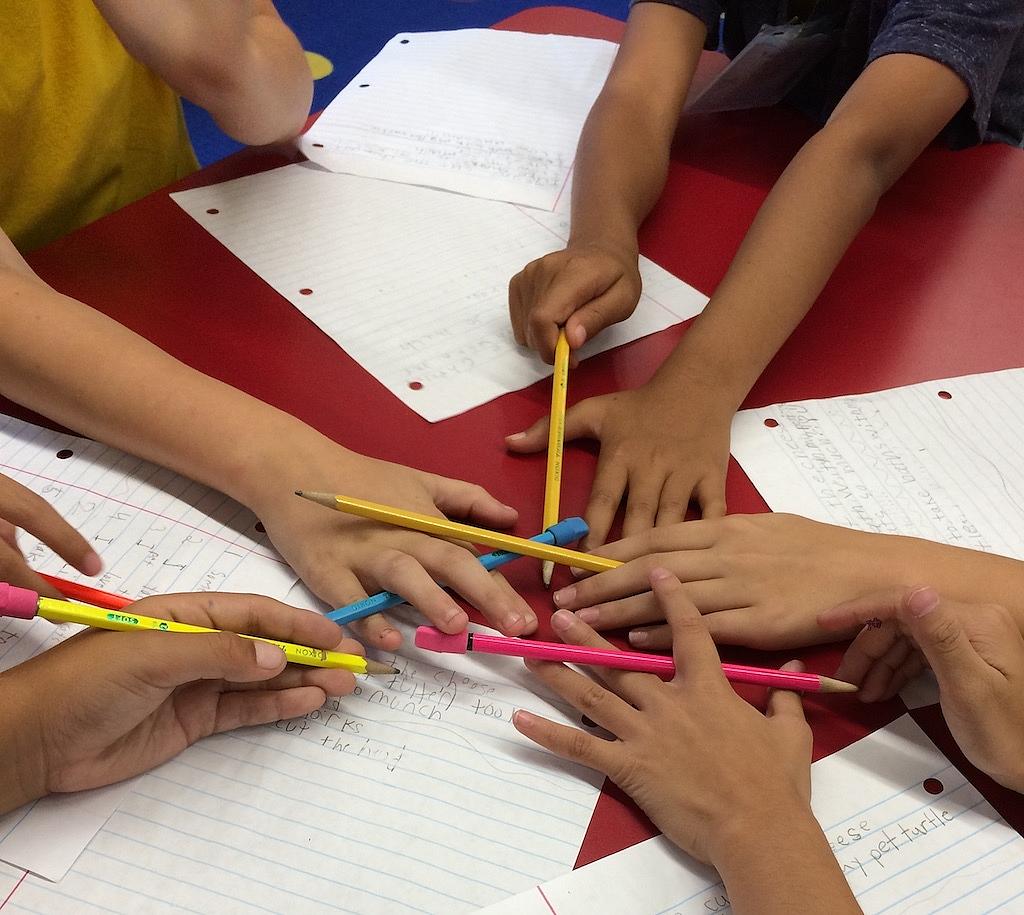

Credit: Margo Perin

Third-grade teacher, Tracy Henry, points to an American flag hanging in her classroom at Schaefer Elementary. The flag is melted along the edges, it shows just how hot the classroom got when the Tubbs fire swept through Santa Rosa and miraculously missed the school.

“I have kids telling me still, oh Ms. Henry I lost my stuffed animals that were in the garage and I know that they burned in there and it makes me very sad,” she said. “You know, those little things were people to them.”

Half of Henry’s students lost their homes that year. This year, she has five students in her third-grade class who lost homes. This trauma is impossible to ignore in the classroom. Behavioral problems have spiked since the fires. According to 2018 data from First 5 Sonoma County, 84% of early childhood care providers noted increased aggression, impulsivity, and sadness among children. Henry has noticed this too.

“Last year we started noticing a whole lot of behavioral issues, and everyone was like what is going on, what is going on," she said. And we finally started to realize that the adults have been processing the fires since day one and they’ve been taking care of all of the things that need taken care of. The kids have really put themselves in the back seat. They don’t want to be in the way, they don’t want to bother, they don’t want to take away from the parents who need to do the things they do. But the problem there is they haven’t had the chance to process their own feelings.”

In addition to literacy, math and other school subjects, trauma recovery has been added to the list of things that Henry has to help her students learn. Thanks to the non-profit, California Poets in the Schools, she has some help. Poet Margo Perin is working with Henry’s third-grade class this year.

“Poetry is a really easy way to express yourself because you don’t have to worry about grammar or punctuation,” she said. “There’s a direct link between what you’re feeling and what you’re thinking and the printed word.”

Perin tells the students to write a poem about advice from an animal. The classroom is silent as the third-graders race to finish their poems. Then Perin tells them to put their pencils down. 8-year-old Delila Stone, who lost her home in the Tubb’s fire, is one of the first to volunteer to read hers aloud. It’s called, Advice from a Llama.

“From now and on, never give up and never be mean,” she reads. “But when some things are tough, be kind and enjoy the sunlight.”

After she finishes, I ask if writing the poem helped her to process what’s she’d been through. When she first started writing, it was sad, she tells me, but then she changed her mind and made sure it had a happy ending. At the end of the class, I ask the classroom teacher, Tracy Henry, how long she thinks it will take for her students to recover.

“When you lose like that, I don’t think it’s ever over, but I think we can heal and what we’re doing to get kids to communicate, I think they’ll be better," she said. “In a way, I think they’ll be stronger better people because they’ll have empathy that others don’t because they know where they’ve been”

This story was produced for the USC Annenberg Health Journalism Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Northern California Public Media.]