Of Floods and Fish: How Natural Forces and Cultural Conflict Shaped Klamath's Foodscape

This story was produced as part of a larger project for the 2019 California Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Hey, Klamath: Where Do You Get Your Food? Do You Get Enough to Eat?

A Piece of Your Spirit': Feeding Each Other in Yurok Country

Residents Say Klamath Needs a Grocery Store, But Can The Community Support One?

Of Floods and Fish: How Natural Forces and Cultural Conflict Shaped Klamath's Foodscape

Looking To Tradition May Help Solve Food Scarcity In Klamath, Panel of Native Speakers Says

Food Council Starts Food Rescue Project As CDBG Dollars For Pacific Pantry Runs Out

"This Is Exciting!": Mobile Produce Pantry's First Klamath Stop A Hit

Partnership Adds Klamath To Mobile Produce Pantry's Permanent Schedule

A local fishermen uses a gill net on the Klamath River in this 1978 photo.

Courtesy of the Del Norte County Historical Society

Hop Norris says he is the youngest documented fish warrior.

Named "Hoppow" in honor of his birthplace, a Yurok village on the Klamath River, Norris was six months old when the United States declared him a domestic terrorist. It was 1978. His mother, father and many others were fighting to regain their rights to fish and hunt in their ancestral grounds.

Native people across the country were taking part in the American Indian Movement and American Rights Movement, Norris said. His parents and other Yuroks were fighting to regain things that had been taken from them, he said, including their traditional hunting and fishing grounds.

Norris was also born the same year Congress passed the American Indian Religious Act, enabling native peoples to practice their religion without fear of persecution. This included hunting and fishing, but, Norris said, his people still had to fight for their rights.

“My dad was threatened that if he didn’t stop, they were going to come and take me and my mother and he wouldn’t see us anymore,” Norris said. “And he didn’t stop. That didn’t stop them. They were this big group of people that were like-minded and upset and willing to do whatever it took.”

There’s more to the story of how Klamath residents feed themselves and their families than geography, transportation and economic forces. There are also the natural forces of the river that shares the community's name altering the landscape itself, and the cultural conflict that have shaped generations of Yurok people.

Susan Masten was born in Crescent City, but her home was at Requa. Owner of the Steelhead Lodge, Masten would become one of the founding members of the Yurok Tribe. She served on the Yurok Interim Tribal Council and the Yurok Tribal Council. She was tribal chair for two terms.

Though she moved away from Del Norte as a fourth-grader, Masten spent summers at her grandparents’ house, fishing and participating in ceremonies, mostly Brush Dance, the White Deerskin Dance and the Jump Dance, to balance the world. Masten said she was 11 the first time she danced.

In addition to their home in Requa, at the mouth of the Klamath River, Masten said her grandparents had a three-bedroom house near Brook’s Riffle, about 20 miles upriver. She remembers a wood stove, an outhouse, a washbasin, kerosine lamps, cows, chickens, fruit trees, roses and a huge garden.

Back then, the town of Klamath had a movie theater, garages, gas stations, a bowling alley and large grocery stores, Masten said. Visits to town were rare for her family, but every time they did make the trip, Masten remembers, her grandfather would treat her to penny candy.

Then, in 1964, the flood came.

“The flood took everything,” she said. “And that’s what took our cabin upriver.”

Also known as the Christmas Flood of 1964, an atmospheric river starting on Dec. 21 caused several area waterways, including the Klamath, to swell beyond their banks. According to a California Department of Water Resources bulletin published in January 1965, the runoff that resulted “produced peak stages and peak flows that exceeded previous records” set nine years earlier during the “hundred year flood of 1955.”

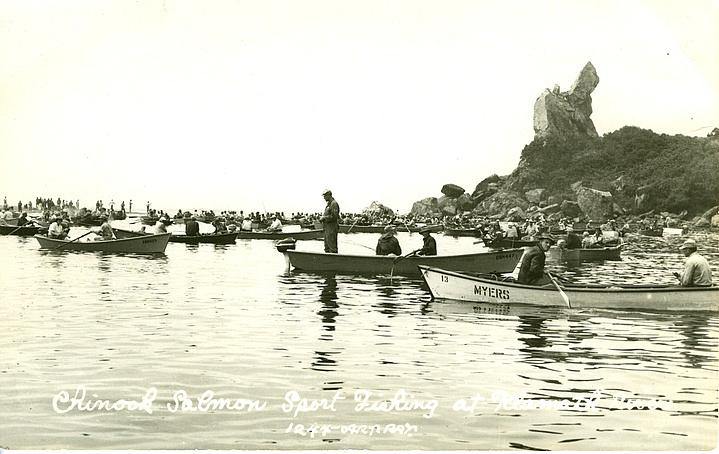

Recreational fishermen at the mouth of the Klamath River. Photo: Courtesy of the Del Norte County Historical Society

On the upper Yurok Reservation, at Weitchpec, about 30 miles upriver, the Klamath crested at 70 feet in the early morning hours of Dec. 23, 1964, according to the Department of Water Resources bulletin. During the 1955 flood, the Klamath peaked at 50 feet. In Klamath Glen, about three miles from U.S. 101, the Klamath River peaked at 55.4 feet at 2 p.m. on Dec. 23, 1964, according to the Department of Water Resources. In 1955 at Klamath Glen, the river crested at 49.7 feet.

Masten said her grandmother’s house -- with its china cabinet that housed a collection of teacups and old pictures of relatives in oval frames from the early 1900s -- went in the flood. Even her dog, a border collie named Waguey, went missing, though he returned home about two weeks afterward, she said.

“His paws were all bloody and he was really really thin, but he made it home,” Masten said. “My grandpa babied him and he made it. They didn’t think he was going to make it, but he made it. It’s one of those stories you see in the movie theater, like ‘Lassie Come Home.’”

Since floodwaters swept away the Klamath town site, the community moved to a new area east of U.S. 101. People thought it would grow again, but it never did, Masten said. There was a post office, a bait and tackle shop and grocery stores that had meat counters and fresh produce. But it never did come back from the flood, she said.

“Now the tribe’s reviving it,” Masten said. “Now we have the hotel and the casino and the gift shop, the visitors center, and we have the little cultural knowledge park that has a model home and a sweat house. The tribe’s done more to revive Klamath since the flood.”

Deeper than the physical changes from the 1964 Christmas flood are the scars left behind from the Klamath Salmon Wars.

On a sunny June morning at Vita Cucina bakery in Crescent City with her mother Lavina Mattz Bowers, Masten described the hostility among white anglers when the native population were finally able to fish without having to obtain a license.

The non-native fishermen began pressuring their Congressman and Senator to make traditional gill netting illegal. They held a big parade with a eulogy for the Klamath, which was dying because the Yuroks were allowed to fish. There were bumper stickers — “can an Indian and save a salmon,” according to Masten.

When the Yurok people began protesting a Department of the Interior decision prohibiting them from fishing for the sake of conservation, Masten said, “it started to get really ugly.”

Federal and state agents showed up in full riot gear as native people began setting their gill nets, she said. The agents’ jet boats could swamp the natives’ wooden and tin boats. They dragged native fishermen by the hair, held their heads underwater and arrested them.

“Several of our people have felonies because of fishing,” Masten said. “Which is so crazy today. They’re trying to get them expunged and they should because it’s not right.”

When Masten’s description of the events of the 1978 Klamath Salmon Wars prompted her mother to leave the restaurant, she said many Yuroks still feel emotional about that time, even four decades later. She compared it to post-traumatic stress disorder in war veterans.

“Every time the state or the feds were mentioned, they just went kind of crazy and if you talk to them now, too, it still brings up emotions,” Masten said. “They would cry. It was so intense.”

On Sept. 24, 1969, Masten’s uncle, Raymond Mattz, was fishing with other people on the river when a California game warden confiscated five of his gill nets. This action would bring Yurok fishing interests before the highest court in the land. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in the Mattz v. Arnett, would ultimately lead to a series of conflicts between native and federal and state agencies called the Klamath Salmon Wars.

According to a description of the case, the central question was whether or not Mattz’s gill nets were on land within the Klamath River Indian Reservation when the state confiscated them. Established in 1855, the reservation was a narrow strip of land extending within one mile on either side of the river for a distance of about 20 miles from the mouth.

The State of California argued that since a statement in an 1892 Act of Congress that opened the area to non-native settlement referred to the Klamath River Indian Reservation in the past tense, the land’s reservation status had been terminated.

However, the Supreme Court ruled that since there had been repeated recognition of the land’s reservation status after 1892, the Klamath River Reservation was still in existence and the confiscation of Mattz’s gill nets occurred within Indian country.

“It reaffirmed that was Indian country,” Masten said of the Supreme Court’s decision.

When the state assumed jurisdiction over the Klamath River, Yuroks had to hide to fish, Masten said. They fished at night. Following the Mattz case, Masten said, native fishermen began fishing during the day, creating conflict with non-native recreational anglers who felt a sense of ownership on the river, Masten said.

“You had people saying we were catching thousands of fish and hauling them off the reservation and so then they started putting pressure on the congressman and the senator to do something about it,” -- to make gill netting illegal -- she said.

After the Salmon Wars, Masten said, she began organizing native fishermen, helping them realize they needed to have input in drafting fishing regulations. She said she told them they needed to work with biologists, but since they worked for the state and federal governments, many native fishermen were unwilling.

Masten said she brought a biologist who was a native woman from Canada and, with many Yurok fishermen, created an Indian Fisherman’s Association with Masten as the chair.

Mattz v. Arnett reaffirmed the Yuroks’ right to fish and hunt on the river, Masten said, but it didn’t define the allocation of fish natives were entitled to. Natives claimed they had never given up any of their fishing rights and were entitled to 100 percent of the catch, she said. Working with the Klamath Fisheries Management Council, the Pacific Fisheries Management Council and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, they picked a year that had an abundance of fish.

“We got them to say we were going to take 50 percent and they needed to manage for it,” she said. “We worked with a solicitor and the Department of the Interior. In the mid ’80s, 80,000 fish was our allocation. That would have meant there were 160,000 fish available to harvest that year.”

Since then, the tribe and many fishermen’s associations are allies when it comes to advocating on behalf of the health of the Klamath River. Many of these concerns stem from a fish kill on the river in 2002 that involved some 34,000 dead salmon due to poor water conditions, warm temperatures and draught.

Today, the Yurok Tribe is one of the signatories to the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement. The states of California and Oregon, the U.S. departments of the Interior and Commerce, conservation groups and other tribes have also signed the agreement, which authorizes the removal of four dams on the Klamath River. The dams' owner, PacifiCorp, is also a signatory.

This agreement created the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, a nonprofit tasked with removing the J.C. Boyle, Copco 1 and Copco 2 and Iron Gate dams, which are blamed for parasitic infections lethal to juvenile salmon.

On July 31, representatives from seven different watersheds pulled their kayaks into the Yurok Tribe’s boat ramp near Requa. It was the end of the third Rios to Rivers international exchange. The program’s ultimate goal is to bring youth representing 22 different watersheds to witness dam removal on the Klamath River in 2022, Executive Director Weston Boyle told the Wild Rivers Outpost.

The young activists had put in at Happy Camp, rafted to Soames Bar and met Ancestral Guard founder Sammy Gensaw III near the Yurok village of Sregon. The Ancestral Guard is a youth-led nonprofit organization that focuses on the rights of indiginous people to their rivers.

With Sammy leading the way in a redwood canoe, Ancestral Guard co-founder Peter Gensaw and Tribal Chairman Joseph L. James welcomed the youth with prayer and song.

“There are so many similarities,” Peter Gensaw said of the youth activists fighting for their rivers. “No matter how far we are from each other — different countries — the youth still have one problem, dams on the river. That’s one of the main reasons we come together.”

###

Jessica Cejnar reported this story as part of her University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2019 California Fellowship. The Center’s interim engagement editor, Danielle Fox, contributed engagement support to this article.

Do you have questions about what you just read or a personal story about this issue? Share your feedback here and reporter Jessica Cejnar will get back to you.

[This article was originally published by Wild Rivers Outpost.]