How bad is the air quality on the Nipomo Mesa? Spikes in pollution are ‘off the map’

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Monica Vaughan, a participant in the 2019 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Health alert: Air quality warning issued for Nipomo Mesa advises residents to stay inside

Live updates: Will off-roaders be banned from Oceano Dunes? Decision day is here

Dust from the dunes: Our investigation of air quality and health on the Nipomo Mesa

State Parks now has ‘workable plan’ to reduce Oceano Dunes riding area and dust by 2023

Do you live on the Nipomo Mesa? Here’s what you need to know about air quality

This is the deadliest year at the Coeano Dunes. What is State Parks going to do?

Health on the Nipomo Mesa: Join us for an open house and forum on air quality

California State Parks could be sanctioned for ignoring scientists on Oceano Dunes dust

Bad air forces people inside in this coastal California town. Is it a crisis or exaggeration?

You ask, we answer: What are the health risks of air quality on the Nipomo Mesa?

How pollution from a California State Park is putting a coastal town’s health at risk

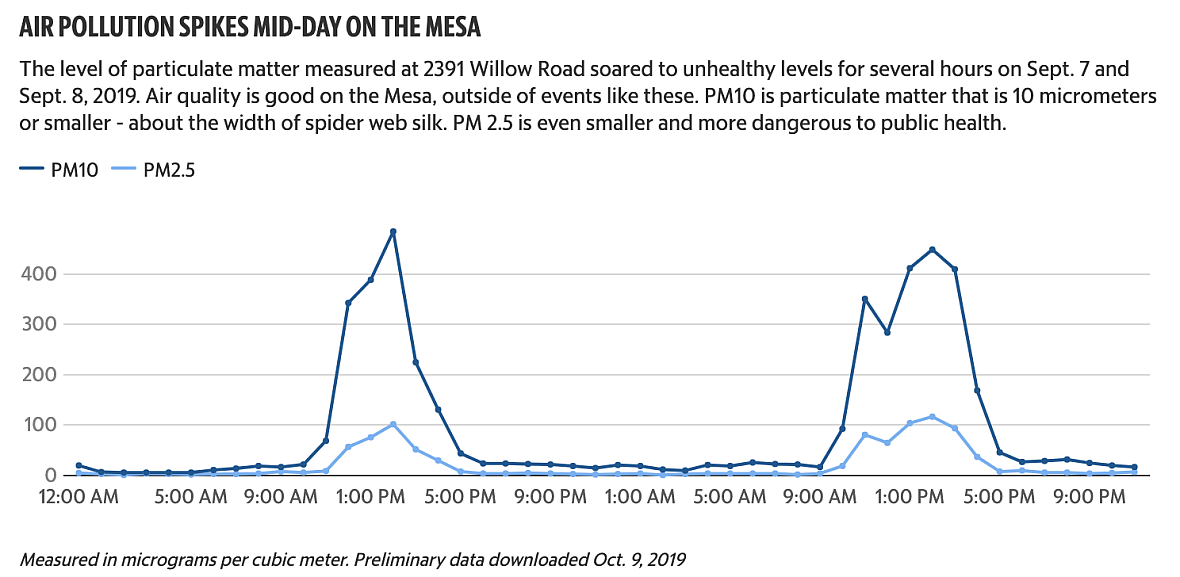

Chart: Monica Vaughan Source: California Air Resources Board

Plumes of dust that waft across the coastal community on the Nipomo Mesa frequently drive air pollution levels above state standards — and that’s happened every year for decades.

Particulate matter pollution in the most affected neighborhood violated state standards 47 days in 2018 and an estimated 42 days in 1999, records show. Some years in between were far worse, with as many as double the number of days in violation.

Those statistics show a measurable problem that has triggered action from local regulators. But the number of violations fails to communicate just how high the levels of air pollution spike during dust events.

The Tribune reviewed public records and shared the findings with multiple air-quality experts, who called the trends unique and outside the scope of air quality standards meant to protect the general population.

Exposure to high levels of particulate matter is a health risk. But there is a gap in current scientific research about the real risk of what people on the Mesa experience: years of repeated exposure to extremely high, short-term spikes.

Patricia Koman is a research investigator in environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan, with an expertise in the health effects of air pollution. She helped form the scientific rationale for current national air-quality standards.

The situation is “off the map of traditional sources of air pollution” and doesn’t fit the national standards, Koman said. Still, it “should require imminent action to protect public health.”

Here’s what the data show:

AIR POLLUTION SPIKES ON THE NIPOMO MESA AT MIDDAY

Air quality on the Nipomo Mesa is good most of the time, outside of these events that usually last for a few hours at around midday.

Here’s what the spikes looked like two days in a row on a weekend in September.

Some days air on the Mesa reaches well above that number, but does not exceed the state standard because of low levels other times during the day.

AIR QUALITY IS GOOD IN OTHER AREAS OF SLO COUNTY

Spikes of particulate matter are unique to the Nipomo Mesa area in comparison to the rest of the county.

That was the case in mid-September, and most other days. Atascadero sometimes has high PM 10 levels, and pollution is sometimes bad countywide due to nearby wildfires.