How pollution from a California State Park is putting a coastal town’s health at risk

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Monica Vaughan, a participant in the 2019 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Health alert: Air quality warning issued for Nipomo Mesa advises residents to stay inside

Live updates: Will off-roaders be banned from Oceano Dunes? Decision day is here

Dust from the dunes: Our investigation of air quality and health on the Nipomo Mesa

State Parks now has ‘workable plan’ to reduce Oceano Dunes riding area and dust by 2023

Do you live on the Nipomo Mesa? Here’s what you need to know about air quality

This is the deadliest year at the Coeano Dunes. What is State Parks going to do?

Health on the Nipomo Mesa: Join us for an open house and forum on air quality

California State Parks could be sanctioned for ignoring scientists on Oceano Dunes dust

How bad is the air quality on the Nipomo Mesa? Spikes in pollution are 'off the map'

Bad air forces people inside in this coastal California town. Is it a crisis or exaggeration?

You ask, we answer: What are the health risks of air quality on the Nipomo Mesa?

DMIDDLECAMP@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

The California Department of Parks and Recreation has known for decades that off-road vehicle activity at its park on the Oceano Dunes contributes to a plume of dust that’s a health risk to downwind communities.

Yet the agency has fought enforcement of clean air rules, failed to meet regulators’ requirements and, in an apparent effort to dodge responsibility, has looked for other factors to blame for poor air quality — even though State Parks’ own research found dust emissions are higher where vehicles drive.

The Tribune recently learned State Parks invested $437,500 on a multi-year study to determine whether phytoplankton — a microscopic form of marine life — contributes to poor air quality, despite years-old findings that the bulk of particulate matter found in air quality monitors on bad air days is crustal matter like dust or soil.

Meanwhile, harmful particulate matter continues to drift across the Nipomo Mesa from the Oceano Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area at levels that violate the state’s own air quality standards, put children and seniors’ lungs at risk, and force residents to bunker indoors dozens of times a year.

On Monday, the Off-Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation Division of State Parks will go before a hearing board for allegedly violating the most recent order to reduce emissions. It will be eight years and two days after the county of San Luis Obispo adopted a regulation directing State Parks to reduce dust emissions from the Oceano Dunes to natural levels by 2015.

That never happened.

STATE PARKS ORDERED TO AIR QUALITY HEARING BOARD

Faced with being found in violation of state and local clean air laws in 2018, State Parks agreed to an abatement order to reduce dust emissions from the off-highway vehicle park 50% by 2023 and submit annual work plans.

“State Parks got off to a great start. They put in mitigation measures and we could see in monitoring a reduction in (particulate matter),” said Karl Tupper, an air quality specialist at the San Luis Obispo County Air Pollution Control District.

“Not much has happened since then,” Tupper said. “We’ve been trying to work with State Parks in good faith to get them to put in some meaningful mitigation. To date, we’re at an impasse here.”

The current director of the Off-Highway Vehicle Division of State Parks, Dan Canfield, told The Tribune the agency is walking a tightrope attempting to balance competing interests with contradictory demands, including environmental and air quality requirements, and a legislative mandate to operate Oceano Dunes as an OHV park.

“We’re doing our best to create projects to work toward solutions,” Canfield told The Tribune. Yet, mitigation efforts continue to be delayed.

The county Air Pollution Control District requested a hearing after it determined a work plan submitted by State Parks was insufficient and failed to follow the recommendations of scientists.

The hearing board could order State Parks to fence off a 48-acre section of the riding area that research shows produces the most dust — as recommended by a group of scientists — or it could issue fines or order larger closures.

The off-roading community fears such efforts to curb air pollution will eventually lead to a complete shutdown of the Oceano Dunes park — the only place in California where vehicles are allowed on both the beach and the sand dunes — and they’ve adopted a “no net loss” strategy to fight any reduction in riding areas.

Fencing off additional areas to promote islands of vegetation could reduce dust, without shutting down the park.

“I firmly believe we can (continue to) have vehicles on the dunes. It’s not going to look like it is right now,” Air Pollution Control District officer Gary Willey told The Tribune. “It might have to be trails through vegetation.”

County Supervisor Bruce Gibson said county leaders have been ineffective in solving the problem “because of the politics of some of its (board) members.”

“There are forces that could and should compel State Parks to do the right thing, namely the APCD Hearing Board and the Coastal Commission,” he said.

OCEANO DUNES PARK MAIN SOURCE OF DUST

Wind-blown sand in a dune ecosystem is natural, but nowhere else on the coast is there a plume like the one that comes from the direction of the Oceano Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area.

A Tribune analysis of meterological data found that the high spikes in particulate matter at the air quality monitor on Willow Road (called CDF) occur only when strong winds blow directly from the direction of the Oceano Dunes riding area.

A panel of internationally recognized scientists, experts in wind-blown dust and geology, was appointed to oversee dust reduction efforts. The members of this Scientific Advisory Group were selected and approved by the state Air Resources Board, the county Air Pollution Control District and State Parks.

The Tribune asked the Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) to explain the current scientific understanding of the relationship between vehicles and dust.

The plume isn’t necessarily caused by vehicles kicking up dust that drifts downwind, the group said, and it’s not vehicle emissions. Rather, “the sand is more emissive than it would be in the absence of OHV activities.”

The Desert Research Institute, a Nevada-based research nonprofit hired by State Parks to study the issue, published a report in 2013 that outlined the results of tests on the surface of sand in hundreds of locations on the Oceano Dunes. That research continues today.

Using a portable instrument called a PI-SWIRL, researchers are able to measure the potential for wind erosion or dust emissions from surfaces in high-wind conditions.

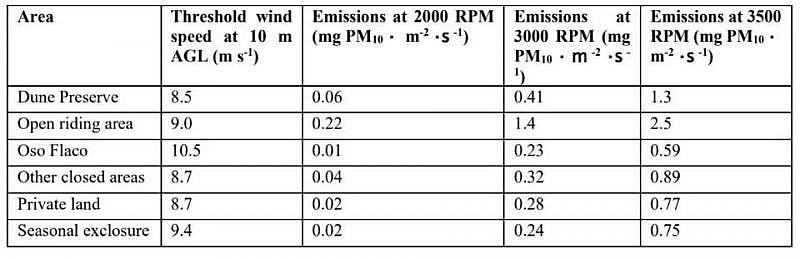

Dust does blow from non-riding areas, but areas where vehicles drive are generally five to seven times more emissive in high-wind conditions than areas where vehicles are not allowed, based on the findings by the Desert Research Institute.

The physics of how vehicles create more dust is unclear. Still, the SAG said emissions are “related to the vehicles constantly re-working the surface of the dunes.”

State Parks has known this for at least 25 years: An agency document says so in no uncertain terms.

“Recreation in the SVRA produces PM10 emissions by disturbing surface sands in the dune ‘play area,’ ” says a 1994 State Parks General Plan Amendment for the Oceano Dunes SVRA.

Yet Canfield recently told The Tribune he is “not going to to speculate” about whether vehicles contribute to the problem. The agency is investing in identifying other sources.

“The importance of these other sources is how much (particulate matter) do we own at the monitor,” Canfield said. “The more of these other sources that we can explore and determine what level they are ... helps us get a better idea of when we’ve achieved our goals.”

CHASING OFF-SHORE SOURCES OF PARTICULATE MATTER

Significant scientific questions remain about the exact role vehicles play in reducing downwind air quality, particularly how much dust blows naturally from the dunes and how much is caused by vehicles.

That gap in information has been used to delay action.

“Do I believe dust is being kicked up from the vehicle?” county Supervisor Lynn Compton said. “Of course, I’m not an idiot. But I don’t know if its twice as much or 90 times. Before I shut down a $200 million outfit, don’t you think we should know that?”

State Parks has indicated in past documents that it could not comply with county regulations to reduce dust because the level of natural dust was never identified. The county rule directed State Parks to answer that question, and the Scientific Advisory Group has underscored the importance of planning that research as soon as possible.

A study that found off-shore phytoplankton on fencing and monitors first appeared when State Parks was ordered before a hearing board. State Parks didn’t formally submit the study, but the off-roading community presented it as evidence that vehicle activity isn’t the problem.

An elemental analysis by the Air Pollution Control District a decade ago found that, on bad air days, the predominant compounds found in air quality filter samples were elements from the earth’s crust such as silicon, iron, aluminum and potassium — not dust from the nearby refinery, not sea salt and not phytoplankton.

Yet, public records show State Parks is spending nearly half a million dollars of public funds to expand on that research to determine the source of dust in downwind communities, an action one county supervisor called an attempt to “deflect and confuse.”

“I’m surprised and concerned at the magnitude of State Parks effort to try to undermine the existing scientific information that has clearly identified dust at the riding area as the predominant cause of the air quality issue,” Gibson said. It “seems to point to a concerted effort to try to cloud the clear conclusions of existing scientific information.”

State Parks officials say they’re committed to improving air quality.

“Regardless of what level the operation is contributing, we do manage a landscape of open sand dunes that’s upwind from a residential area that suffers from high particulate matter and meteorological events,” Canfield said.

“We’re still figuring out the whys, to do some hows. How can we achieve those goals of reducing emissions and reducing the numbers at those monitors. The big goal is improving air quality.”

Agencies tasked with protecting public health — including the county Air Pollution Control District Board and California Coastal Commission — have so far been ineffective in holding State Parks accountable to significantly improving air quality.

“We expect the agencies are going to do their job. They haven’t done their jobs,” said Linda Reynolds, who moved to the Mesa just a few years ago without knowledge of the air quality problem.

“I’m disappointed in all of them: the Coastal Commission, the Board of Supervisors, and especially State Parks.”

This article was originally published by The Fresno Bee.