Investigation finds LA Harbor-area smog challenges grow as new health threats emerge

This story was produced as a project for the 2017 California Data Fellowship, a program of USC's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

How to look up oil wells – and the chemicals they might be using – in your neighborhood

Investigation finds LA Harbor-area smog challenges grow as new health threats emerge

San Pedro High School student investigates neighborhood air pollution

Trucks move around the port of L.A. complex in Wilmington on Friday, Aug. 3, 2018. In addition to the nearby refinery, the port traffic is a source of pollution in Wilmington.

For this series, Southern California News Group analyzed air-pollution data collected by South Coast Air Quality Management District and the Port of Los Angeles in Wilmington, San Pedro and Long Beach. The project focused on fine particulates, which include diesel emissions, released from 2010 to 2017.

The data comprised hourly readings from five sites around the region, was received in response to public records requests.

SCNG also installed portable PurpleAir monitors (purpleair.com) in three homes in Wilmington and San Pedro to provide additional data on particulates. The monitors record particulate levels every minute. This was done to cross-check the official data and to quantify exposure to pollution for individuals interviewed for the project. The devices were installed from mid-February to mid-March.

SCNG undertook this project in partnership with USC’s Center for Health Journalism, which supplied training, support and funding to purchase air pollution monitors. SCNG was solely responsible for the editorial content of the series.

On school days at 10 a.m., the back doors of Saints Peter and Paul School in Wilmington fly open and elementary students in powder-blue shirts rush out for recess.

Its yards are large enough for the 74-year-old Catholic school to offer a variety of outdoor activities including soccer, basketball, archery, volleyball and football.

As the fields fill with activity and excited chatter, a machine on the school’s roof that looks like a large pressure cooker silently records toxic health threats in the air.

It’s one of several Port of Los Angeles air-quality monitors. The nation’s heaviest-trading commercial marine complex belches diesel soot and poisonous gases about five blocks from the school.

The ports of LA and Long Beach together emit 100 tons of smog daily, according to air quality officials. Even more toxic chemicals are spewed by traffic, refineries and rail yards.

A Phillips 66 refinery stands a mile away, and two more refineries operate within 3 miles, routinely flaring cancer-causing plumes.

An analysis by Southern California News Group and USC’s Center for Health Journalism of data recorded by that monitor showed dangerous levels of diesel exhaust and other microscopic pollutants called PM2.5 blanketing the school from 2010 through 2017.

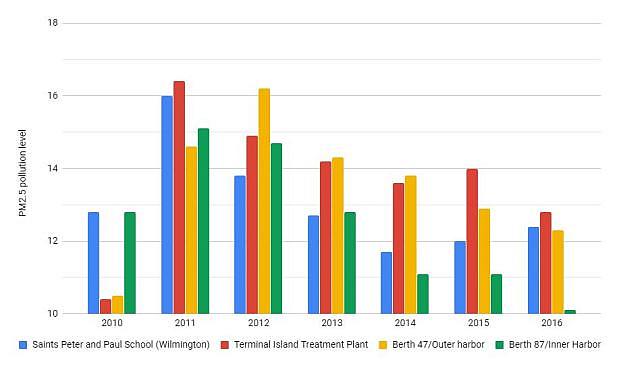

Average annual levels of particulate matter (PM2.5) at Port of Los Angeles’ four air monitoring stations, from 2010-2016. (Graphic by Ian Wheeler. SCNG)

PM2.5 gets its name from its tiny size – less than 2.5 microns – smaller than a human hair. The particles are small enough to move through the lungs and into the bloodstream, where they can circulate carcinogens, lead, arsenic, sulfates, nitrates and other gases, chemicals and metals into the brain.

These particles can cause long-term damage to developing lungs, according to leading health organizations.

Elderly and sick adults are also especially vulnerable to the particles, which can trigger chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, cancer and strokes. A growing body of research from scientists around the globe shows PM2.5 may play a part in dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, increased blood pressure, obesity and diabetes.

At Saints Peter and Paul School, PM2.5 concentrations of roughly 13 micrograms per cubic meter of air were recorded, on an annual average basis, throughout the seven-year analysis. The Environmental Protection Agency says breathing anything over 12 micrograms regularly is hazardous.

// 800 ) { vizElement.style.width='630px';vizElement.style.height='799px';} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width='630px';vizElement.style.height='799px';} else { vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height='799px';} var scriptElement = document.createElement('script'); scriptElement.src = 'https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js'; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement); // ]]>The LA port’s other air-monitoring sites tell a similar story:

- Annual average concentrations exceeded federal standards from 2011 to 2016 near a water-reclamation plant on Terminal Island, a man-made industrial island used by the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports.

- Particulate pollution was dangerously high along San Pedro’s outer harbor near Cabrillo Beach from 2011 to 2016, and at the inner harbor near Battleship Iowa from 2010 to 2013. Levels were just within acceptable limits in 2010 and 2017 at the outer harbor station, and from 2014 to 2017 at the harbor’s outer edge.

- Fourth of July fireworks and wildfires deliver some of the most extreme pollution spikes, according to monitors. Rush-hour traffic routinely sends pollution levels soaring.

Even low levels of pollution worry scientists and health officials.

“As air quality in general improves, and as we get better at measuring and understanding these particles, we’re able to see adverse effects at lower and lower levels,” said Jill Johnston, an assistant professor at USC who researches air pollution and its impacts in Los Angeles. “The body of literature over the last decade shows there can be long-lasting chronic effects at low levels.”

Smog challenges rise

The ports and regulators routinely tout strides in recent decades toward a smog-free horizon.

But little progress has been made since 2011. Pollution levels are increasing at some sites, according to monitor data. And business at the ports is growing.

South Coast Air Quality Management District is working with environmentalists to block a new railyard that would exacerbate emissions near homes and schools. BNSF Railway’s Southern California International Gateway project would build an intermodal railway in Wilmington adjacent to West Long Beach, generating millions more truck trips per year.

“As cargo throughput continues to grow, emissions will grow,” Carter Atkins, an environment specialist for the Port of LA told the California Energy Commission in May 2017. “We need new strategies to protect gains and continue to reduce emissions each year.”

Tainted air, while worse in port-facing communities, is widespread across the region. Southern California exceeds the federal Clean Air Act’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards in both fine particulates, or PM2.5, and ozone pollution.

The U.S. EPA set a 2021 deadline for the region to reach acceptable PM2.5 levels, but the state is seeking an extension to 2025 by classifying itself in “serious” rather than “moderate” nonattainment of air-quality standards.

Newly funded assembly bills 617 and 134 will funnel more than $1 billion for clean-vehicle incentives and community air-monitoring programs to help meet the target.

The investment comes with a mandate to find new ways to reduce PM2.5 and ozone levels below federal standards, and to develop a statewide network of community air monitors.

Air-quality regulators are now looking for ways to reduce smog in the hardest-hit communities.

San Pedro, Wilmington, Harbor City, Paramount, and neighborhoods in south and east Los Angeles are among those being considered for early intervention.

A couple crosses a pedestrian bridge as they take a morning stroll through Waterfront Park in Wilmington Monday, March 26, 2018. (Daily Breeze)

Meanwhile, researchers are amassing a mountain of evidence showing there is no such thing as a safe level of air pollution exposure.

This growing awareness prompted the EPA to lower the acceptable level of chronic PM2.5 exposure from 15 to 12 micrograms per cubic meter of air in 2012.

A comprehensive global research review published in January by Jonathan E. Thompson of Texas Tech University found negative effects at even lower levels of exposure.

“This has led some investigators to suggest that there is no ‘safe’ level of exposure to particulate pollution,” Thompson wrote, in a study published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. He found that 4.2 million people around the world could be dying prematurely each year, especially from heart and respiratory failure, because of exposure to PM2.5.

Connecting pollution to disease

Rebecca Diaz’s house faces a sea of port-related warehouses and shipping hubs along truck-heavy State Route 47 to the Port of Los Angeles.

The Wilmington cottage, downwind of Andeavor and Phillips 66 refineries, sits surrounded by auto shops and wrecking companies.

The beeps and whirrs of Semis echo through the neighborhood like angry industrial wildlife.

But, inside, the sounds of industry disappear. Visitors are welcomed to the home with a fresh pot of coffee, a soft couch, and clusters of family photos. Diaz raised 10 children there.

“When we first moved here, you would get a headache if you left the windows open,” said Diaz, 86. “It’s better now. The refinery isn’t as strong as it was then. And there used to be an oil well in the back alley. They took it out.

“They found cancer in my kidney 10 years ago and removed it. But I still feel like a teenager.”

Southern California residents are slightly more likely to get cancer than the national average of 4 in 10 people, said South Coast Air Quality Management District Health Effects Officer Jo Kay Ghosh.

“There is quite a lot of evidence (PM2.5) has cardiovascular disease effects, including mortality,” Ghosh said. “And there’s quite a lot of evidence for respiratory health effects. The air toxins that people in our basin are exposed to will increase your cancer risk by 900 in a million.”

A couple crosses a pedestrian bridge as they take a morning stroll through Waterfront Park in Wilmington Monday, March 26, 2018. (Daily Breeze)

Connecting the neighborhood pollution to, for example, Diaz’s kidney cancer – a disease linked to breathing PM2.5 pollution – isn’t yet possible.

But the link between smog and disease is clear. Childhood asthma rates in this South Bay region rank second-highest in the state. More than 1 in 10 kids has been diagnosed with the chronic disease, according to the County of Los Angeles Public Health Department.

The majority of those affected are residents of low-income communities of color.

The state’s CalEnviroScreen tool – designed to identify areas most damaged by pollution – rates the Wilmington Catholic school and its neighborhood between the 91st to 95th percentile for high levels of poverty and pollution.

The school’s monitor is one of just a few dozen used by the South Coast Air Quality Management District to estimate pollution across 6,745 square miles with 15 million residents.

The district has three air monitors in Long Beach but none in other nearby communities. It relies on an algorithm to estimate smog levels.

Its south Long Beach monitor logged hazardous levels of particulates from 2011 through 2015, and again in 2017.

Solutions evade regulators

Southern California’s efforts to meet federal pollution standards have been stymied on multiple fronts:

- New diesel engines are cleaner because of added filters and other measures. But commercial trucking companies have been slower than regulators would like in upgrading their fleets. Some companies simply ignore costly state requirements. For example, three fuel suppliers were fined a total of $785,000 in April for failing to meet low-carbon rules.

- Electric vehicles aren’t yet ready for widespread use.

- A controversial cap-and-trade Regional Clean Air Incentives Market (RECLAIM) program to cajole refineries and other industrial polluters into reducing nitrogen oxides emissions also failed to yield anticipated progress. The incentive system only enticed businesses to cut about half the desired amount of pollution.

- Oil refineries report only a fraction of the emissions they release, according to a 2016 study by Swedish researchers on behalf of SCAQMD. The state ruled last year that all refineries must install fence-line air monitors by 2020.

- Equations used by the EPA to calculate air pollution have repeatedly been shown to underestimate the true amount and types of breathing hazards. The SCAQMD relies heavily on algorithms to represent what the 15 million residents across four counties in its jurisdiction are breathing.

Regulators are pinning their hopes on still-developing technologies. Both ports are testing a wide range of equipment to develop a clear roadmap to a zero-emissions future, which they promise to realize by 2035.

Natural-gas engine technology is considered the region’s best bet in meeting immediate federal guidelines.

“We’ve succeeded in commercializing, with industry partners, a near-zero natural-gas truck engine,” SCAQMD spokesman Sam Atwood said. “We think that, in order to really get it into fleets in significant numbers, it’s going to take a lot of incentive funding.”

But environmental groups don’t want to compromise on such technologies. They’re pushing for only zero-emissions solutions.

Sylvia Betancourt, a project manager with Long Beach Alliance for Children with Asthma, advocates for the electrification of trucking fleets and other freight equipment rather than “near-zero” alternatives.

“One of the main problems in our communities is this cumulative impact,” Betancourt said. “Areas become completely overburdened by air pollution. We want (a solution) that’s not pollution at all because we need that in overburdened communities.”

Diaz said she’s happy with air quality improvements in her Wilmington neighborhood in recent decades, but still has concerns.

“I got a letter a while back that said it was recommended not to dig too deep into the soil,” Diaz said. “There are petroleum pipelines under the home.”

Complaints about pollution? Who to call

Report idling buses or trucks near schools and homes to California Air Resources Board, at 800-952-5588

For smoking vehicles call 800-END-SMOG with license plate, description and location

U.S. EPA has an online complaint system for harmful emissions or environmental damage. Visit calepacomplaints.secure.force.com/complaints/

Los Angeles Public Health Department will investigate health concerns of those living and working near oil wells and trucking operations. Visit publichealth.lacounty.gov/report/phreports.htm or call 211

Report harmful emissions from oil refineries, production fields and other industrial sites to South Coast Air Quality Management District at aqmd.gov/home/air-quality/complaints or by calling 800-CUT-SMOG

To find out about SCAQMD community events, including meetings about air quality concerns, visit aqmd.gov/nav/about/initiatives/community-efforts

Find in-depth information about specific oil wells using a street address or oil field name here: maps.conservation.ca.gov/doggr/wellfinder/#close

Look up reports of oil well operations, emissions, chemical injections and more here: xappprod.aqmd.gov/r1148pubaccessportal/

Coalition for Clean Air’s statewide C.L.E.A.R. air-monitoring network reports around-the-clock readings of pollution at ccair.org/our-goals/clear-network/ccas-air-quality-monitoring-network/

The U.S. EPA’s AirNow network reports regional pollution levels around the country at airnow.gov

Sign up for notifications of oil refinery flaring events at aqmd.gov/home/rules-compliance/compliance/r1118/flare-event-notifications

[This story was originally published by the Daily Breeze.]